Dr. Edith Eger was just a teenager when the Nazis ripped her and her family from their home and sent them to concentration camps.

The girl who once had She enjoyed a normal life – she went to ballet classes and spent time with her sisters in Hungary – He survived a year in a camp with his two sisters, while his parents were murdered in the gas chambers.

For a long time he avoided talking about the horrors he witnessed and focused on starting a family in the United States. She eventually became a psychologist and realized that to heal she needed to confront her trauma, forgive, and stop thinking of herself as a victim.

And throughout his nearly 50-year career, he worked to do the same for his patients.

Dr Eger, 96, told DailyMail.com: ‘I can’t change my blood. I can change the way I see things and I believe that change can be synonymous with growth.’

Dr. Edith Eger pictured left before she and her family were sent to the camps in 1944. She was liberated from the camps in 1945 and immigrated to the United States four years later, where she earned her doctorate in psychology.

Dr. Eger enjoyed doing ballet during her youth in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. While in Auschwitz, Dr. Eger said she was forced to perform a ballet routine, earning her the title “The Ballerina of Auschwitz.”

Dr. Eger was born Edith Eva Elefant, the youngest daughter of three children to Lajos and Illona Elefant, in Czechoslovakia in 1927. The family moved to Hungary, where Dr. Eger became interested in dance and gymnastics and joined to the Hungarian gymnastics team in the early 1940s.

But the comforts of normal life were stripped from her when she and her family were sent to Auschwitz in 1944. Shortly after arriving, Josef Mengele, the famous Nazi doctor, sent her mother to the gas chambers.

Mengele then allegedly asked Dr. Eger to perform a dance for him. The dancer did, saying in her 2019 memoir ‘The Choice’: “The barracks floor becomes a stage at the Budapest opera house.”

This performance earned her the title of ‘The Dancer of Auschwitz’ and a loaf of bread, which she distributed among the girls in her area.

From there, Dr. Eger endured starvation, beatings, and death marches, moving from camp to camp as the Nazis lost ground in the war.

In May 1945, after the U.S. Army liberated the camp she was in, she met the man who would become her husband, Bela Eger.

The two had their first daughter, Marianne, and then fled to the United States amid threats from the communist government of Czechoslovakia in 1949.

When she arrived in the United States, just four years after leaving the concentration camp, Dr. Eger did not want to think about the past. She was focused on establishing a “normal” American life with her family.

Dr Eger told DailyMail.com: “I had kept a lot of things inside me because I didn’t want my children to be different.” I just wanted to be a good Yankee Doodle.

He went to college in 1969 and earned his degree in Psychology from the University of Texas, El Paso. He then earned his doctorate at William Beaumont Army Medical Center at Fort Bliss and opened a therapy clinic in La Jolla, California.

Dr. Edie as a child, with her family, the Elefants, before being sent to the camps, around 1932. Her parents, Lajos and Ilona, died in Auschwitz. Dr. Eger married her husband in

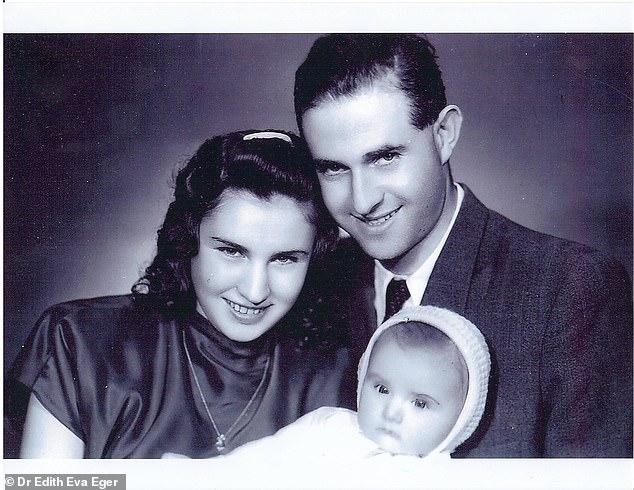

Dr. Eger with her husband Bela and their first-born daughter, Marianne, around 1947.

Then in the 1980s, he visited Washington, DC, and went to the Holocaust museum. There, Dr. Eger saw a photo of a girl she swore looked exactly like her.

This experience moved her and she decided that she needed to start talking about what had happened to her, not only so that people would not forget the horrors of the Holocaust, but also so that she could heal.

She said: “I think it’s important that we recognize that what goes out into our body doesn’t make us sick, it’s what stays there.”

This became the cornerstone of his therapeutic practice. She encourages people to share what they’ve been through and accept it, so they can stop thinking of themselves as victims.

It is common for people who have gone through traumatic situations to feel like victims. But this mindset is cyclical, he said, and leads people to fall into toxic patterns.

Someone who considers themselves a victim of life will likely end up in two scenarios, Dr. Eger said. First, they will likely end up in the same situation: surrounded by people who will hurt them.

Or second, they are likely to become victimizers themselves, turning their bad feelings into other people’s problems.

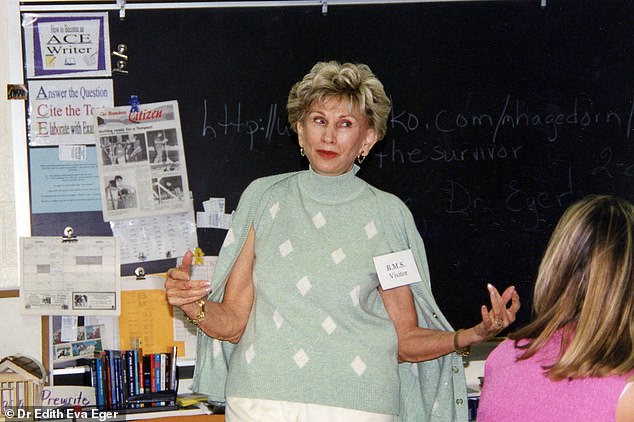

Dr. Eger giving a presentation to a classroom full of students in the 1980s

To achieve this, Dr. Eger recommends thinking about the options you have in front of you and making decisions that will help you grow and forgive yourself and those who have wronged you.

Dr. Eger said, “The more options you have, the less you will feel like a victim.” It’s not about who I am, it’s about what they did to me.

If you have trouble forgiving those who have wronged you, Dr. Eger said, you can rethink the idea of forgiveness all together.

He said that forgiveness is an act of self-care that really helps you, and you don’t have to think of it as something that serves the person who hurt you.

This will lead to radical growth and change for the better, he said: “I think forgiveness is a gift you give yourself to stretch rather than thank yourself to shrink.” So don’t call me a psychiatrist, call me stuffy, I think it’s good to expand your comfort zone.’

Other things you can do to overcome your past include focusing on the person you want to be.

To do this, he recommends starting the day by visualizing yourself satisfied at the end of the day. This will help you make decisions throughout the day that will help you feel better and more present at the end of the day.

Dr. Eger said, “You are going to be what you practice.” Decide in the morning what you want to feel at night.’

This will help you focus on each day as it comes and be grateful for the time you have, he explained.

Dr. Eger added: “You will look in the mirror and see yourself satisfied.” Because life is perhaps only one day, the morning sun may or may not return. I don’t know. There is no guarantee.’