A shipwreck dubbed the ‘Titanic of the Alps’ will return to the surface, more than 90 years after it first sank beneath the waves.

The Säntis sank to the bottom of Lake Constance on the Swiss-German border in 1933 when she was deemed unseaworthy and too expensive to scrap.

But at a depth of almost 210 m (690 ft), darkness and lack of oxygen have left the 48 m (157 ft) steamship remarkably well preserved.

Plans have now been approved to remove the ship from the lake bed and put it on public display.

Silvan Paganini, president of the Ship Salvage Association that is trying to achieve the feat, said: ‘We want to present to the public what we have here; What a monument we have of our predecessors. That is the main objective.”

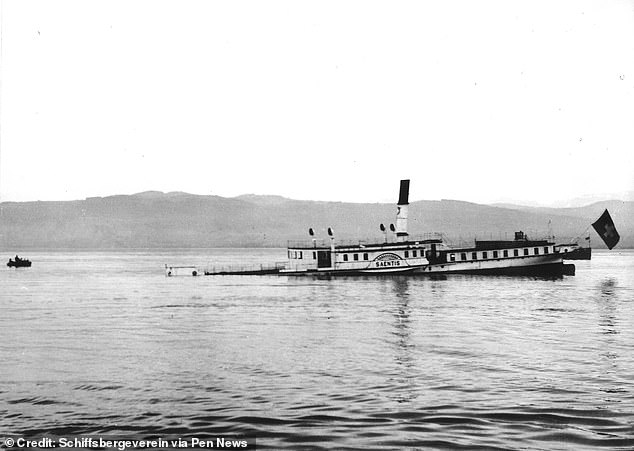

The Säntis (pictured), a steamship nicknamed the ‘Titanic of the Alps’, will be rescued from the bottom of Lake Constance, where it sank more than 90 years ago.

Due to the darkness and lack of oxygen on the lake bed, the Säntis is better preserved than the Titanic. You can see in this photo how the original paint on the ship’s sign is still visible after 90 years underwater.

This photograph from 1898 shows the ship at the Romanshorn shipyard. If she can be removed from the bottom of the sea she will return to this shipyard to be restored.

The Säntis was originally a ferry service that carried passengers across Lake Constance.

It operated for 40 years and carried up to 400 passengers at a time.

But after an ill-advised decision to change its engines from coal to oil and an economic crisis in the area, the decision was made to sink the ship.

The Swiss Lake Constance Shipping Company, then owner of the ship, took the Säntis to the center of the lake and sank it to a depth of 210 m (690 ft).

There it remained, largely forgotten, until an underwater survey in 2013 discovered the location of the wreck.

The ship was then purchased by the Romanshorn Ship Salvage Association and plans were put in place to return it to the surface.

In 1933 the ship was deemed unseaworthy and too expensive to scrap, so it was taken to the center of Lake Constance and sunk.

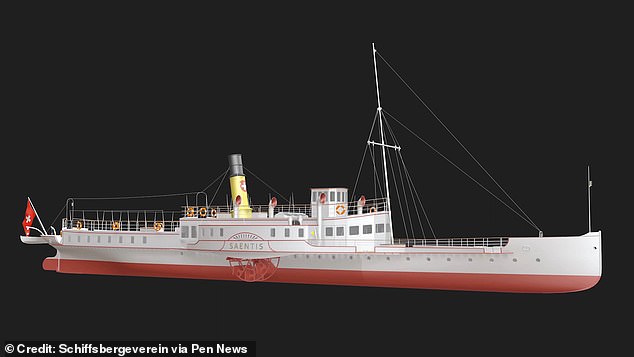

This 3D model demonstrates what the Säntis would have looked like in its prime. Due to the mountain lake conditions, many of these features, such as the paint paddle wheels, still survive to this day.

This boat was almost forgotten until 2013, when a survey of the lake discovered the location of the wreckage. Here you can see the boat’s oar that remains almost intact.

The Säntis earned the nickname “Titanic of the Alps” due to a number of similarities between the two ships.

Paganini said: “The steamship Säntis has a three-cylinder steam engine like the Titanic.

“A three-cylinder steam engine is very rare, and this is one of the similarities from a technical point of view.”

According to Paganini, the two ships also sank in a very similar manner.

He said: “The stern rose into the air with the flag flying high, that was also similar to the Titanic.”

In reality, the Säntis is even older than the Titanic, having been commissioned 20 years before the Titanic sank.

However, due to the conditions of the deep mountain lake, it is in much better condition.

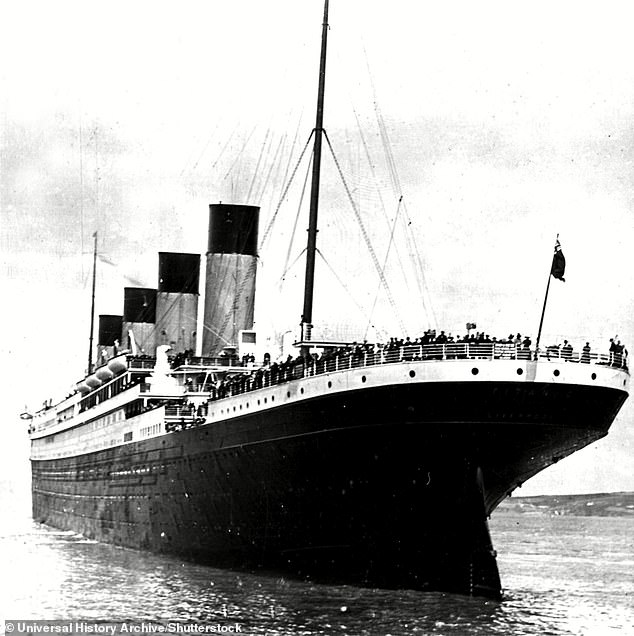

The Säntis has been compared to the Titanic (pictured) because both used a rare three-cylinder steam engine and sank bow-over-stern.

The Säntis, shown here while still in service, is actually older than the Titanic, having been commissioned 20 years before the Titanic sank.

The ship is so well preserved that divers found the original paint visible, leaving the ship’s name still proudly displayed.

But time may be running out to save the Säntis, as it is now threatened with destruction by an invasive species of mussels.

Quagga mussels, an introduced species, were first found in Lake Constance in 2016 and have since spread rapidly.

A 2022 study by the Baden-Württemberg Fisheries Research Station found that mussels are now the “dominant species” of the lake bottom community.

The concern is that the mussels may soon cover the Säntis with a thick layer.

Mussels have already been found in the Säntis chimney, leading to fears that time to act is limited.

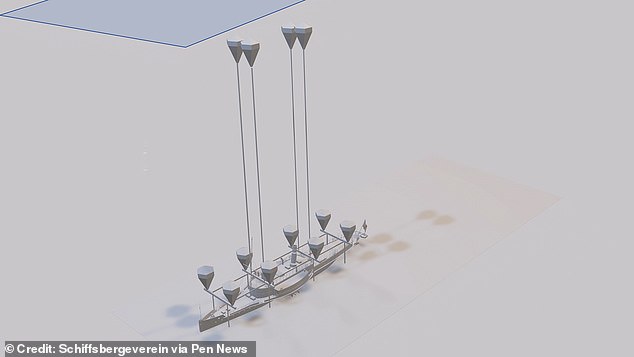

To raise the Säntis (pictured), rescue teams will need to attach lift bags to the boat, which will fill with air and drag it from the lake bed to the surface.

For 40 years, the Säntis operated as a passenger ferry on Lake Constance on the Swiss-German border, carrying up to 400 passengers at a time.

Satellite images and surveys of the lake have revealed exactly where the ship is located on the lake bed.

As this plan shows, lift bags will first be used to drag the ship to a depth of 40 feet (12 m) before the final surface access takes place in April.

Efforts to lift the ship are scheduled to begin in March of this year.

Paganini said: ‘The cheapest solution is to lift bags. They’re like balloons that work underwater, you fill them with air and then they go up.’

Divers will attach the bags to the boat before inflating them to bring the boat closer to the surface.

The first ascent will take Säntis from the seabed to a depth of just 12 meters before the final ascent to the surface takes place in April.

The Säntis will then be renovated at the nearby Romanshorn shipyard, where it was already renovated in 1898.

Paganini says the plan is to display the ship in a museum somewhere in Switzerland.

However, the canton of Thurgau explicitly ruled out financially supporting the project, leaving Paganini to search for an alternative buyer for the wreck.