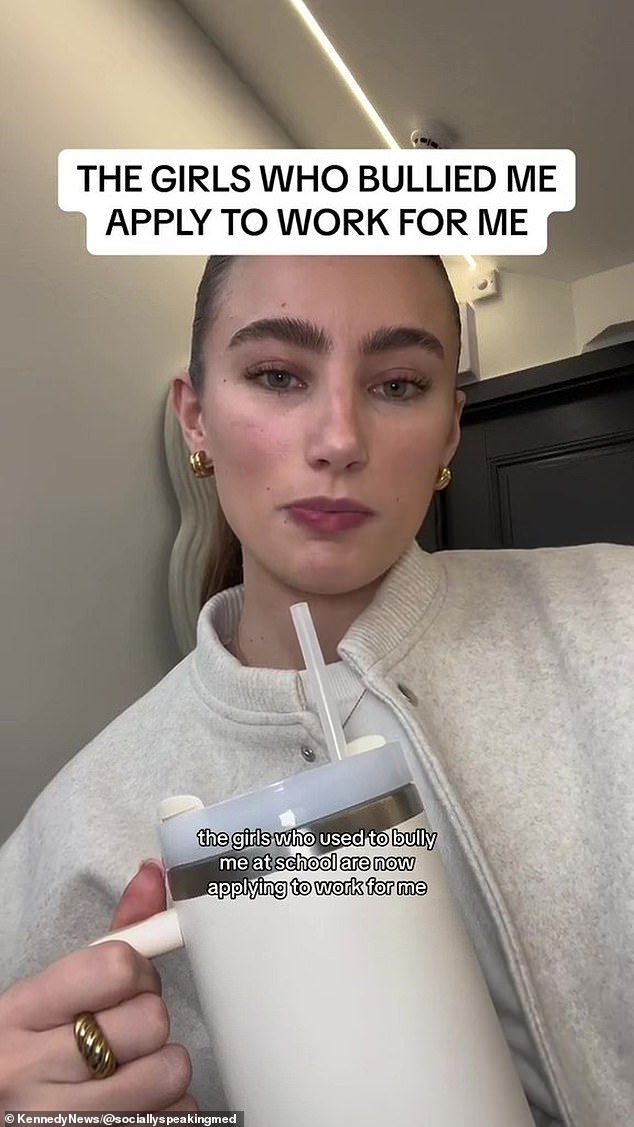

A 23-year-old CEO said she turned down three girls who bullied her at school when they applied to work at her successful company, adding that “what they offered” meant they “didn’t get anywhere in life.”

Vicky Owens, from Stockport in Greater Manchester, is the founder of Socially Speaking Media, based in Alderley Edge, a thriving six-figure company.

According to Vicky, she posted a job ad on LinkedIn earlier this year after wanting to hire more employees to work at her social media agency.

She says she couldn’t believe it when three girls who once ridiculed her at school applied for the position.

Vicky claims that two of the girls who submitted their CVs used to ignore her at school, but she was shocked to receive an application from a third who actively harassed her.

Vicky Owens, from Stockport in Greater Manchester, is the founder of Socially Speaking Media, based in Alderley Edge, a thriving six-figure company.

Above: Vicky appears with ketchup in her hair in Nando’s while claiming the girl who did it applied to work for her business.

Vicky claims that two of the girls who submitted their CVs used to ignore her at school, but she says she was most surprised by the third girl who applied as she claims he proactively harassed her.

Vicky when she was younger, when she claimed she had been bullied

Vicky claims the third applicant poured yoghurt on her head in the school canteen and covered her in tomato sauce in Nando’s when she was out with friends in Year 10.

Due to the torment she endured at school, Vicky says her mental health took a hit – she began having panic attacks and struggled to leave the house after leaving full-time education.

After sharing her experience on TikTok, the businesswoman claims users quickly suggested getting back at the girls, but Vicky says she was a ‘bigger person’ and ignored their requests.

The entrepreneur has now emphasized the importance of always being “nice” to others because you never know when a personal connection could help you succeed in the real world.

He suggested that the world’s karma would correct itself when he said that “the good you put out eventually comes back to you, even if you feel like it never will.”

Vicky said: “The company started getting bigger and bigger, so I posted a recruiting position and three of the girls who were absolutely horrible to me in high school applied for the job.”

The entrepreneur has now emphasized the importance of always being “nice” to others, as you never know when a personal connection could help you succeed in the real world.

Vicky receiving the keys to her new office in Cheshire as her thriving business expanded

Vicky, pictured at the Nobu Hotel in Marrakech, now travels around the world by plane with her clients.

Vicky says she believes she was harassed because she was an “easy” target who “didn’t talk much”

“Two of the girls were people who just wouldn’t give me the time of day at school and then the other girl was someone who threw yoghurt at my head in the canteen in Year 10.

‘Another time I was with some of my friends in Nando’s in year nine or ten and a girl walked by and threw ketchup in my face.

‘I don’t know why people did this to me. I think he was an easy target because he was quiet and didn’t say much. Both incidents were committed by girls who later applied to work for me.

“I think in a very sad way I got used to it. [the bullying]. When you’re younger, everyone thinks it’s funny.

‘The moment I got pinched was when I saw that the girl who was horrible to me at school now wanted to work for me. That was a coming full circle moment.

‘I found it very interesting [that they had applied]. He was really puzzled whether to answer them. [the job applications] or reject them.

“Some people on TikTok were very unpleasant and suggested that I invite them for an interview and make them feel terrible, but that’s not part of my character.”

‘I just ignored them and every time we go to hire every other month there are definitely familiar faces on the applications who definitely weren’t horrible to me at school but didn’t give me the time of day.

Vicky said it was a “full circle” moment when the girls who were mean to her at school now wanted to work for her.

Their business, Socially Speaking Media, is a social media agency based in Alderley Edge in Cheshire and currently has a team of four employees.

Vicky, pictured on holiday in Palma de Mallorca, said her advice is to be nice to everyone and not stoop to the level of the bully.

Since setting up her business from her bedroom in 2021, Vicky has collaborated on the Netflix show Emily in Paris, Grace Beverly (pictured with Vicky) and helped clients get featured in Vogue magazine.

‘I started having panic attacks after I finished high school and had to deal with all that. My parents also went through a divorce.

‘It was all the accumulation of torment over the years and then my parents’ divorce.

‘My body was a bit in shock. I kept having them and they got so bad that I couldn’t work or leave the house and therefore had no income, so that’s when I started my business.’

Socially Speaking Media is a social media agency based in Alderley Edge in Cheshire and currently has a team of four staff.

Since starting her business from her bedroom in 2021, Vicky has collaborated with the Netflix show Emily in Paris, Grace Beverly and helped her clients get featured in Vogue magazine.

Vicky said: “We are definitely in a six-figure business and we will be moving into a six-figure business very soon.”

“Although it may seem like it, high school is such a short time [in your life].

‘I would just tell everyone to be nice. I never stooped to their [the bully’s level] and the good you put out eventually comes back to you, even if you feel like it never will.

“If you are consistent and keep your head down, you will eventually see results.”