Taylor Swift and her boyfriend Travis Kelce reportedly traveled to a quaint Northern California town with her A-list partner, Gigi Hadid and Bradley Cooper.

The famous four were in Carmel-by-the-Sea, a charming town located on the Monterey Peninsula, according to Page six.

It was also claimed via DeuxMoi’s Instagram account that the group had been seen dining at French restaurant La Bicyclette.

The NFL player’s mother, Donna Kelce, opened up about their double date while attending QVC’s Age of Possibility Summit in Las Vegas on Wednesday, where Cooper was also in attendance. People reports.

Donna, 71, said she received a photo of her son from the beautiful city and that during the getaway, Travis, 34, learned that Bradley, 49, would also be attending the QVC summit at that his mother would attend.

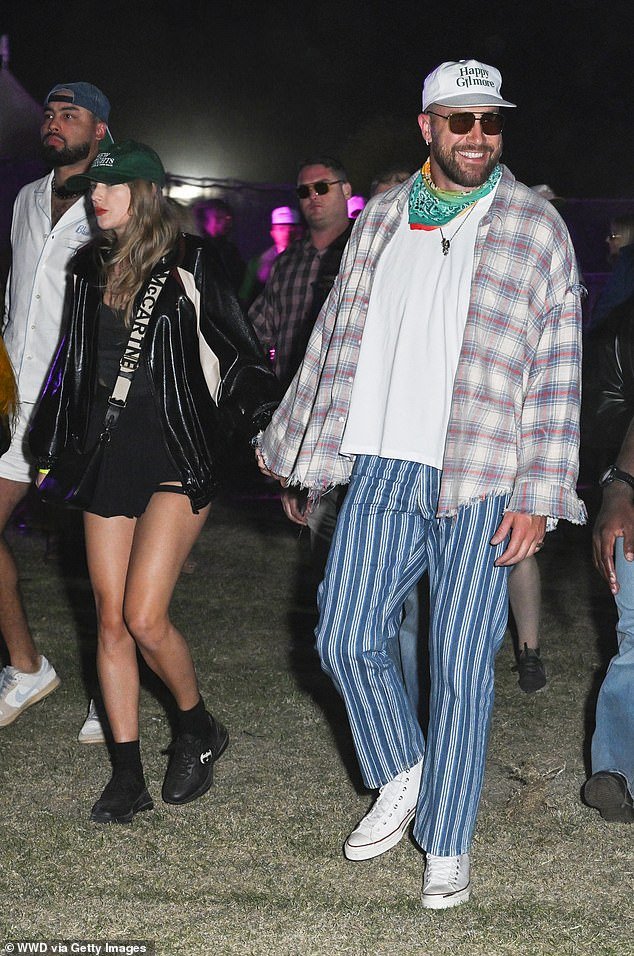

Taylor Swift and her boyfriend Travis Kelce reportedly traveled to a quaint Northern California town with her A-list partner, Gigi Hadid and Bradley Cooper; photographed in January 2024 in Baltimore

A-list couple Gigi and Bradley reportedly joined Swift and Kelce in Carmel; photographed in February 2024 in New York

When they finally met at the summit, Donna allegedly told Bradley, “Travis told me you were going to be here.”

He also said that he would have loved for Travis to have been able to attend the summit, but that he was still working on Are You Smarter Than a Celebrity?

Travis will host the upcoming Prime Video game show, which is a spin-off of Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?

Taylor, 34, and Travis have been everywhere these past few months, with a recent trip to Indio, California, for the Coachella music festival, several weeks after a getaway to the Bahamas.

As for Bradley and Gigi, they’ve been going strong since they were first spotted together in October.

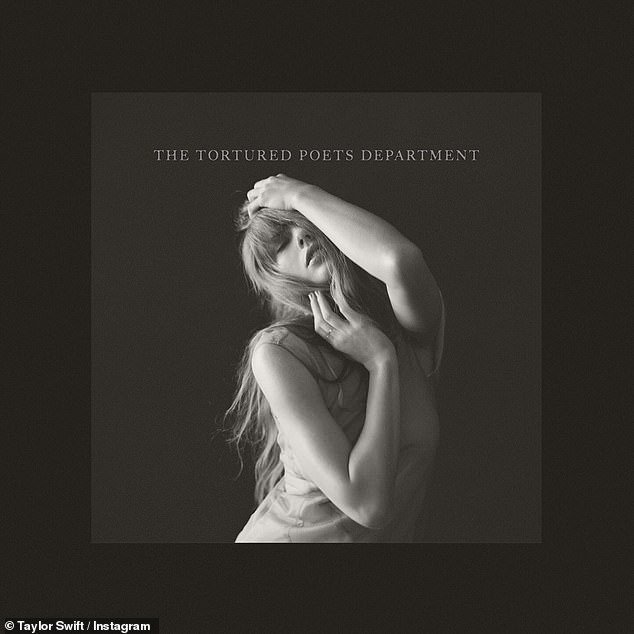

Meanwhile, Taylor’s name has made more headlines following the release of her latest album, The Tortured Poets Department.

Not surprisingly, it has proven to be a huge hit with fans.

On Wednesday, Spotify announced that the album had achieved the honor of becoming its most streamed album in a single week.

It was also claimed via DeuxMoi’s Instagram account that the group had been seen dining at French restaurant La Bicyclette (pictured).

Swift and Travis have been everywhere these past few months, from Coachella to the Bahamas.

Meanwhile, Taylor’s name has made more headlines following the release of her latest album, The Tortured Poets Department.

Since Swift released the record, the album has been streamed more than one billion times on the platform.

‘On April 22, 2024, THE TORTURED POETS DEPARTMENT by Taylor Swift became Spotify’s most streamed album in a single week. The album has surpassed one billion streams since its release,” the streamer announced via X.

From conquering multiple Spotify albums to landing the best-selling album of 2024, the pop star’s latest labor of love so far has her outdoing even herself.

Billboard He is currently predicting that these will be the biggest first-week sales to date for the singer, who will return to The Eras Tour on May 9, 2024 in Paris, France, after a two-month break.

Within three days of its release on Friday, The Tortured Poets Department (TTPD) sold 1.5 million copies in the United States,” according to the outlet.