Every year, an estimated 400 million people visit ski resorts looking for action on the slopes.

But trips to many of the world’s most popular resorts could soon become a thing of the past due to a lack of snow caused by climate change.

Researchers at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, found that one in eight ski resorts will have no snow days by the end of the century.

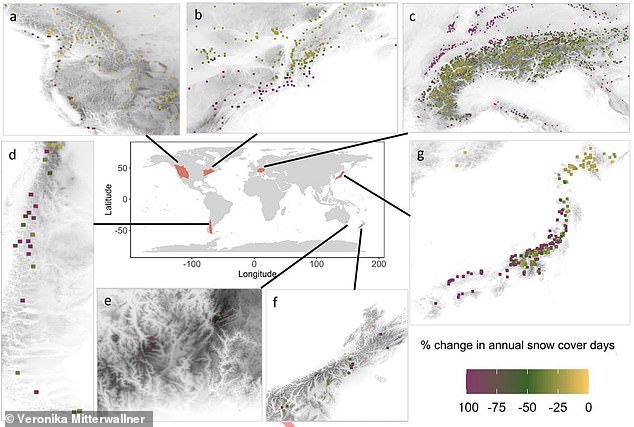

From the Australian Alps to the Andes, this stunning map reveals the areas that are likely to be snow-free or closed in the next 75 years.

So is your favorite resort at risk of disappearing forever?

Your browser does not support iframes.

While skiing is a very popular sport and a very profitable industry, until now there has been little research into how it might be affected by climate change.

To understand what effect a warmer climate might have on skiers, researchers looked at seven popular ski areas around the world: the European Alps, the Andes, the Appalachians, the Australian Alps, the Japanese Alps, the Southern Alps ( located in New Zealand) and Rocky Mountains.

The team then identified which parts of these regions are used for skiing and used climate models to see how many days of snow cover they would receive under different emissions scenarios.

The worst-case scenario is the “very high emissions” case, in which there are no concerted efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In this case, both temperatures and emissions would continue to rise, and CO2 emissions would double by 2100.

Under this scenario, the researchers found that 13 percent of the world’s ski areas would be completely snow-free between 2071 and 2100.

This map shows how each ski area identified by researchers will be affected by climate change by 2100. Purple squares show areas that will not receive days of snow cover, while yellow dots show regions that will not be affected.

Researchers predict that in a high-emissions scenario, Japanese Alps resorts like this one in Niigata could have 50 percent fewer days of snow cover each year.

Another 20 percent would lose more than 50 percent of their snow days at the same time.

If you ski in Japan, the United States or Australia, your favorite places could be in trouble.

Under this scenario, 18 percent of the Andes areas, 14 percent of the Appalachian areas, and 17 percent of the Japanese Alps will no longer have snow cover days by 2100.

However, the hardest hit areas will be ski resorts in the southern hemisphere: the Australian Alps are expected to see 78 percent fewer days of snow each year, and the Southern Alps and Japanese Alps are expected to lose between 51 and 50 percent of its snow. snow days respectively.

European Alps resorts like this one could have 42 percent fewer snow days a year by the end of the century.

Even the European Alps, where 69 percent of the world’s ski areas are located, are expected to have 42 percent fewer days of snow cover by 2100.

The findings come as alpine areas experience rapid warming due to climate change.

Some studies have predicted that almost all Alpine glaciers could disappear completely by the end of the century.

Worryingly, some areas are even expected to fall below the “100-day rule,” suggesting that a resort with less than 100 days of snow cover is not economically viable.

Both the Australian Alps and the Japanese Alps may no longer be viable ski locations by 2100 with only 38 and 86 days of snow each year in a high emissions scenario.

Lead researcher Veronika Mitterwallner told MailOnline: ‘We already observe temporal and spatial changes in reliable snow cover in ski areas, resulting in a concentration in fewer ski areas.

“This has the effect of making skiing less accessible than it was until now, and this trend will be further amplified by climate change in the future.”

Ski resorts in the Australian Alps (pictured) could no longer be economically viable as snow cover days could fall below 100 days.

The study also reveals that ski areas closer to more populated areas will be more affected by climate change.

Densely populated areas will lose 55 percent of snow-covered days in a very high emissions scenario and 49 percent in a high emissions scenario.

Ms Mitterwallner said: “Our study indicates that ski areas in the outer and lower reaches of mountain ranges, as well as coastal resorts, will be particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change.”

Meanwhile, more remote areas, such as the more mountainous regions south of the European Alps, will be less affected.

Researchers suggest this could lead to ski resorts moving to increasingly remote areas.

They suggest this could lead to the degradation of already fragile mountain ecosystems and the loss of local plants and animals.

The researchers, in their article published in PLoS ONEwrites: “This study demonstrates significant future losses in natural snow cover from current ski areas worldwide, indicating spatial changes in the distribution of ski areas, potentially threatening high-altitude ecosystems” .