- Darwin Blanch played his first ATP Masters 1000 event in Miami in March

- His career earnings are $30,000, compared to Rafael Nadal’s $134.7 million.

- DailyMail.com provides the latest international sports news.

A young American tennis prodigy will face 22-time Grand Slam champion Rafael Nadal at his home tournament in Madrid after receiving a wild card entry to the event.

Blanch, 16, is currently ranked 1,028th in the world rankings, but must feel like he has won the lottery after being chosen alongside Nadal for the first round of the clay tournament.

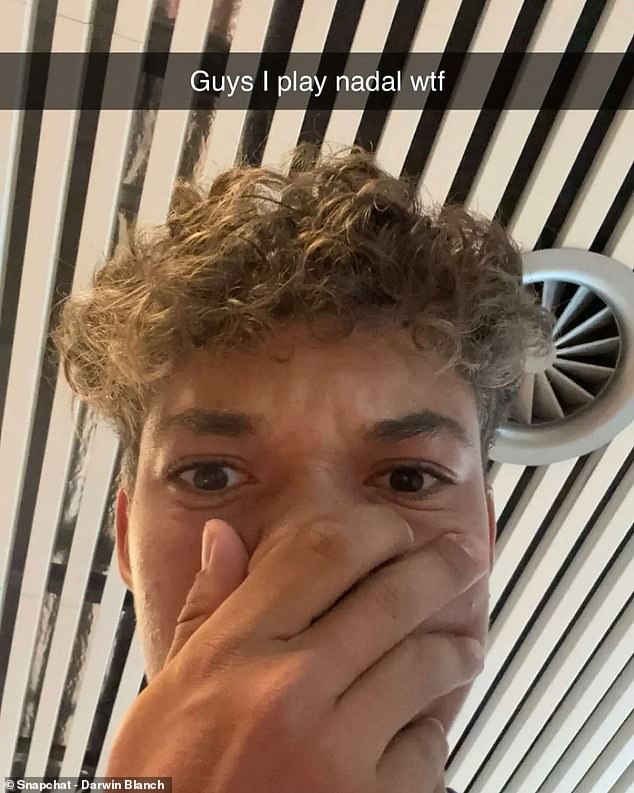

The teenager took to Snapchat completely shocked by the news on Monday and posted a photo of himself covering his face, along with the caption: “Guys I play with Nadal wtf.”

Nadal is a record five-time champion in Madrid, but it is Blanch’s first time competing, and he has career earnings of $30,650, compared to Nadal’s $134.7 million.

The Spaniard has been recovering from an injury and has fallen to 512th in the rankings, which may give Blanch a glimmer of hope ahead of their battle on Wednesday afternoon (Wednesday 4am EST).

Darwin Blanch couldn’t believe it after being tied with Rafael Nadal at the Madrid Open

Blanch played men’s singles at the US Open last year, but is now stepping up.

Blanch, 16, is pictured at Wimbledon last year. She has earned $30,650 so far in her career.

Blanch was born in September 2007 and played his first ATP Masters 1000 event last month in Miami, losing to world number 50 Tomas Machac in straight sets.

He has since traveled to Spain and reached the semi-finals of the lower-ranked M15 Telde, eventually losing to Diego Augusto Barreto Sánchez, after beating three players in the previous rounds.

Elsewhere in the Madrid Open tournament, Carlos Alcaraz has returned from injury to try to win a third consecutive title, but number one in the ranking, Novak Djokovic, is not there.

Alcaraz will compete in his first European clay court event of the season after missing Monte Carlo and Barcelona due to a right arm injury.

The 20-year-old Spaniard begins his title defense against Alexander Shevchenko or Arthur Rinderknech.

Nadal returns from injury and will face a player he had never faced in Madrid

Carlos Alcaraz is back on the court and looking to win a third consecutive Madrid Open title this year.

The winner of the matchup between Blanch and Nadal will face tenth seed Alex de Minaur in the next round.

Nadal lost to De Minaur in the second round of the Barcelona Open last week in his first tournament in more than three months.

Nadal, 37, last won the Madrid title in 2017, when he beat Dominic Thiem in the final.

Three-time champion Djokovic will not play for the second consecutive year in Madrid, reducing his clay court preparations for the defense of his title at the French Open.