The 90 Day Fiancé cast members are shocked after Jasmine Pineda revealed that she has “always” liked her co-star Nikki Exotika and would gladly carry their unborn child during the spectacular reunion show.

In a preview shared exclusively with DailyMail.com ahead of Sunday’s episode, the 37-year-old newlywed makes her explosive confession after host Shaun Robinson, 61, asks a saucy question submitted by a fan.

Jasmine’s candid admission comes just weeks after she announced she would marry husband Gino Palazzolo, 53, in June 2023 in an intimate ceremony attended by just 12 people.

In the preview, Shaun invites TV personalities to answer who, in the entire 90 Days universe, they would like to have children with other than their current partner.

90 Day Fiancé Tell All Cast Members Shocked After Jasmine Pineda Reveals She’s In Love With Nikki Exotika

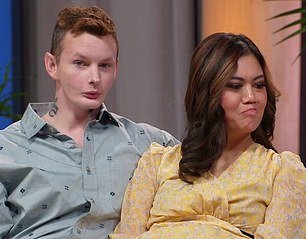

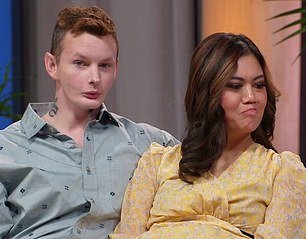

Nikki blushes as Jasmine reveals to the group that she would gladly carry their unborn child.

Without breathing, Nikki, 47, immediately points at Jasmine.

Jasmine then reciprocates his suggestion and confidently responds: ‘I would carry (Nikki’s) baby.’ I like her.

‘I mean, I’ve had girlfriends in the past, so I’m attracted to both women and men. I don’t know, I was always in love with Nikki.

Clearly shocked by this confession, Jasmine’s husband Gino simply says “interesting”, while host Shaun, stunned, replies: “Well, that’s breaking news.”

As Nikki passes out and blushes in the studio, Jasmine quickly stuns the entire room when she casually adds, “Hypothetically, if I were Nikki’s partner, I would fuck her.”

Immediately audible gasps echo through the room.

Nikki, on the other hand, has a big smile painted on her face and is fanning herself coldly.

Jasmine is married to her husband Gino, whom she initially met online in 2019 before getting engaged on season five of 90 Day Fiancé.

Jasmine makes the explosive confession while sitting next to her husband Gino Palazzolo, whom she married in an intimate ceremony in June 2023.

Newly single Nikki seems to be in love with Jasmine’s heartfelt words

Presenter Shaun Robinson is seen looking totally stunned after Jasmine said she would ‘fuck’ Nikki.

It’s not just Shaun who is visibly surprised by Jasmine’s candor, the rest of the couples seem surprised too.

Their romance has been plagued with problems over the years, however, they revealed earlier this month that they quietly tied the knot in a low-key wedding in June 2023.

Reflecting on her big day in an interview with People, Gino said: ‘It was my dream wedding come true. A super amazing day that I won’t forget!’

Jasmine also fainted: ‘It was one of the happiest days of my life.

“I married the love of my life.”

Jasmine said her wedding day was “one of the happiest days of my life.”

Nikki was brutally dumped by her partner Justin Shutencov in scenes that aired last week.

Meanwhile, Nikki is newly single after Justin Shutencov brutally ended their relationship via text on the show’s latest episode.

“I’m beyond devastated right now,” she cried during an emotional confessional after also sharing that her ex had been ignoring her messages.

“He doesn’t even give me the option to talk to him in person.”

Nikki had met Justin when she was 30 and he was 20, and she waited two years into their relationship to share that she is transgender.

90 Day Fiancé Tell All airs this Sunday at 8pm ET/PT on TLC.