QUESTION Why was the Marquess of Clanricarde “the most unpopular man in the United Kingdom”?

This was the 2nd Marquess of Clanricarde, Hubert George de Burgh-Canning (1832-1916), a notorious miser and eccentric who never visited his Irish estates and treated his tenants cruelly.

Clanricarde’s mother was the daughter of George Canning, the Prime Minister. His uncle, Lord Canning, was viceroy of India at the time of the Indian rebellion of 1857. Having no children of his own, he left his nephew a large fortune.

On 10 April 1874, Clanricarde inherited six peerages and became owner of Portumna Castle in Galway, together with an estate of some 57,000 acres.

Clanricarde lived in London, in a luxurious apartment in the Albany building, near Piccadilly.

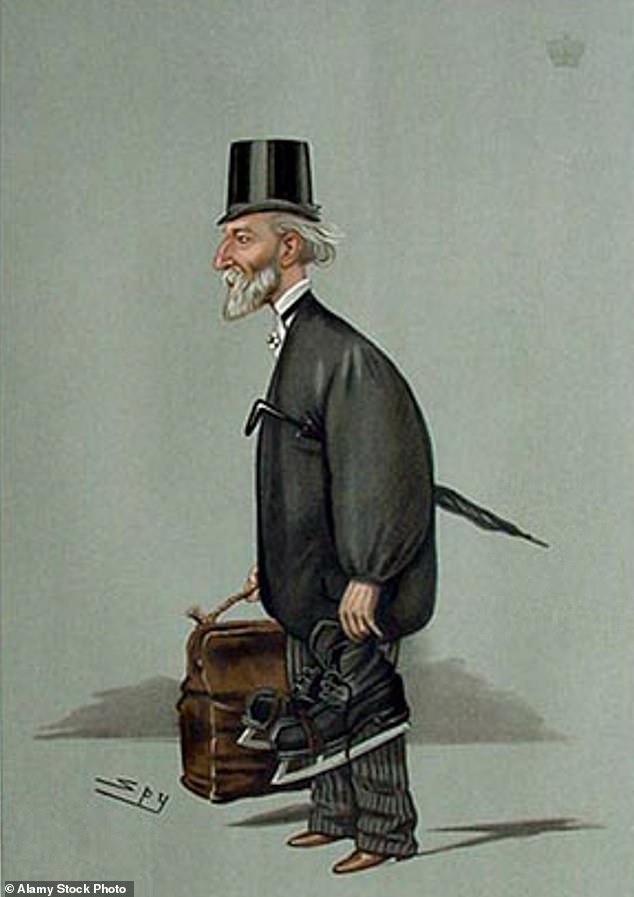

A 1900 Vanity Fair caricature of the 2nd Marquess of Clanricarde, Hubert George de Burgh-Canning, a miserly landowner

Meanwhile, their properties and tenants suffered abandonment. On June 29, 1882, his real estate agent, John Henry Blake, was murdered. In August 1886, several of his tenants were brutally evicted for non-payment of rent.

Their estates became the focus of the Land War, a period of agrarian unrest in which local tenants attempted to obtain fair rents. Despite the insistence of successive Chief Secretaries of Ireland, Sir Michael Hicks Beach and Arthur James Balfour, Clanricarde refused to budge and continued to evict his tenants.

He contemptuously disregarded the Wyndham Land Act of 1903, a scheme which set out conditions for voluntary sale on terms favorable to both landlords and tenants.

Augustine Birrell’s Irish Evicted Tenants Bill of 1907, which sought the compulsory purchase of land from absentee landlords, galvanized Clanricarde into action and he made his only speech in the House of Lords.

On August 6, 1907, colleagues and journalists gathered to witness the speech of this despised figure. Journalist Michael MacDonagh described “a faded, frail, wrinkled figure, leaning heavily on a thick, threadbare umbrella as she wandered feebly, staring straight ahead and seemingly seeing nothing.”

Clanricarde’s speech was full of flowery rhetoric but undermined by his weak delivery.

Clanricarde’s obstinacy gave rise to the Land Act of 1909 which allowed district boards to acquire land by obligation. By July 1915, many of Clanricarde’s properties had finally been removed from his care, resulting in considerable financial loss.

Clanricarde himself was expelled from Albany due to a dispute with his landlords over rent.

Jonathan Sewell, Pembroke.

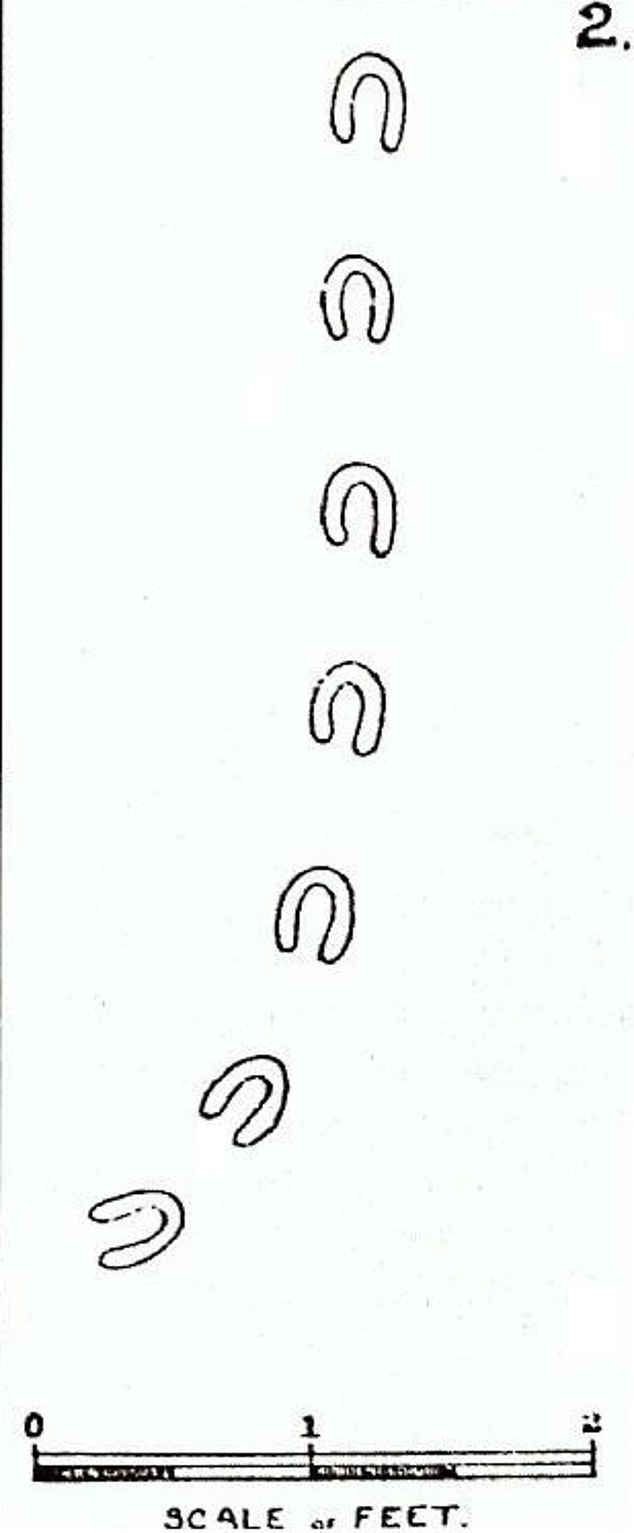

A sketch from the Illustrated London News from 1855 showing what the devil’s hoof prints might have looked like.

QUESTION Have the devil’s hoof prints ever been explained?

The Devil’s Hoof Prints refers to a phenomenon that occurred in February 1855 in Devon. They were a series of hoof-shaped marks found in the snow, covering a distance of around 100 miles across the county and that appeared seemingly overnight.

The footprints were small footprints, resembling cloven hooves, about four inches long, arranged in a single row, and seemed to pass over rooftops, as if the creature creating them had ignored the obstacles in its path. The phenomenon sparked a national conversation about its origin.

Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post was the first newspaper to report on the footprints, describing: “A thrill worthy of the dark ages” with “footprints of the strangest and most mysterious description.”

The national debate took place in the Illustrated London News. Naturalist Richard Owen proclaimed that the tracks were the hind legs of a badger. One writer believed they were the tracks of a bustard, another suggested they were the tracks of a rat hopping through the snow.

One tongue-in-cheek contribution claimed that the tracks were those of the uniped, a rarely sighted mammal that had been sighted by Icelandic explorer Biom Herjolfsson in Labrador in 1001 AD.

Geoffrey Household, who edited a small book of all the correspondence on the subject, believed that they were the traces left by two shackles emerging from a balloon that had escaped its moorings.

Keith Moore, Honiton, Devon.

A pillar of modern parenting, but when were baby pacifiers actually invented and who invented them?

QUESTION Who invented baby pacifiers?

Small clay dolls have been found in Cypriot tombs dating back to approximately 1000 BC, featuring a small hole through which a baby could suck honey.

In 17th to 19th century Britain, a “coral” was a teething toy made of coral, ivory or bone, often mounted in silver as a rattle handle.

The modern rubber pacifier with a nipple, shield and rubber handle design was patented by Manhattan pharmacist Christian W. Meinecke in 1901 as the “Baby Comforter.”

Mrs Sarah White, Newcastle upon Tyne.