My friend thought she was complimenting me, but her words were some of the most hurtful I had ever heard.

Full of sincerity, she told me, “Radhika, you are really pretty for an Indian.”

That was the moment, at age 15, that I realized that no matter how hard I tried to fit in, I would always be seen as “less than” because of the color of my skin.

I am a British Indian and for most of my life I have hated being Indian.

It’s not an easy sentence to write. It makes me very sad to think that I’ve felt this way for so long, but it’s true.

After being told by friends that she was pretty “for an Indian” at 15, Radhika Sanghani (pictured) rejected her Indian heritage. It took her another 15 years to look beautiful. Dress, £905, Mahima Mahajan at lillysboutiquelondon.com

For more than two decades I tried to put as much distance as possible between myself and my ancestry.

Only in the last few years, when Indian culture has become more fashionable, have I started adopting it as well.

I am a first generation British Indian, born in London. My grandparents were originally from Gujarat and eventually moved to Uganda, where my parents were born.

They both came to England as children, but never stopped remembering their idyllic childhood in Uganda, with zebras, monkeys, amazing food and a strong Indian community.

Meanwhile, I grew up in leafy North London, where almost no one in our neighbourhood was brown.

My parents still tried to raise me with our traditions, having a shrine to Hindu gods in our house, celebrating Diwali and often speaking Gujarati at home.

As a child, I loved dressing up in Indian clothes and performing religious rituals, but as I grew up, things changed.

In high school, the differences between my (mostly white) peers and me went from being something we were barely aware of to becoming — sometimes painfully — obvious.

As with teenagers, the most important thing was to fit in. We tried hard to emulate the heroines of our time: Kate Moss, Buffy star Sarah Michelle Gellar, anyone from Friends.

But the white beauty standard of the early 2000s meant I would never be considered beautiful. Even though I had the “right” body type, I didn’t have the “right” features or skin color.

As a teenager, it was all about fitting in and Radhika would never dream of posting a picture of herself wearing Indian clothes on social media.

My difference was highlighted by our school uniform, not the official blazer and skirt, but the unofficial one: skin-colored tights, fake tan, Mac foundation, and lots of bronzer.

Ironically, everyone was trying to look tanner, but none of those measures worked on my skin. If I ever tried (like wearing nude tights that looked strangely pale on me), my classmates would make jokes about it.

I had to fake laugh at many jokes during those years: about Indians and their smelly curries (although I never brought curries for my lunch), Indian accents (although I didn’t have one), and my “big Indian nose” (I did have this one).

At the time, I didn’t even recognize it as casual racism. It was so normalized that, even though it made me feel hurt and angry, I didn’t feel like I had the right to say anything.

I also wanted to fit in so badly that I didn’t want to draw more attention to my difference by speaking out loud. Instead, I laughed at the jokes, hoping that we could move on more quickly.

But all the comments took their toll on me. I internalized that shame and spent the rest of my school and college years trying to anglicize myself as much as possible.

I still wore Indian suits and saris to family weddings and religious celebrations, but I hated how clothes made me feel different.

I was so used to seeing myself in Topshop and H&M that when I wore a sparkly chiffon dress and a bindi on my forehead, I felt like I wasn’t myself.

It would never have occurred to me to post a photo of myself in Indian clothing on social media.

And I had spent so much time trying to be more like my white friends, that now I felt like an imposter at Indian events, too.

In her late 20s, Radhika began to see that her Indian culture was officially in fashion and began to change how she felt about her identity.

I also stopped speaking Gujarati. I spoke it less since my last grandfather died when I was 12, and my parents spoke English perfectly.

Naturally, my family was disappointed. They couldn’t understand why I was so against our culture. Back then, I would put on my headphones and retreat into my temperamental teenage self whenever they tried to talk to me about the issue.

When I started to lose my Gujarati, my mother begged me to continue with the lessons. “If you stop, you will lose it forever and you will regret it when you grow up,” she warned me. I told her I didn’t care.

But now that I’m in my 30s, I can see that he was right. I speak fluent Spanish and Italian, but I can barely speak Gujarati, my parents’ native language.

Just as she predicted, it is something I now regret. But at the time, I felt that my Indian language and culture would hold me back rather than help me.

Unfortunately, everything I experienced in mainstream society seemed to confirm my views. When I was in my 20s, I avoided listing my ethnicity on dating apps, because I noticed that when I did, I got fewer matches.

When I once ran an experiment to test this, creating two profiles with the same pictures of myself (one called Radhika and one called Rachel), Rachel received twice as many likes.

I was so used to downplaying my Indian identity that in my early twenties I was shocked to realise that being Indian was no longer seen as a negative thing.

The turmeric and hot milk my mum used to make me when I was little was now being sold as a trendy turmeric latte for £4.50.

Yoga (something my mother and I had been doing together since I was ten) was now the hottest activity among white women, and Bollywood actress Aishwarya Rai was being labelled the “most beautiful woman in the world.”

It helped that her boyfriend not only accepted her for being different, but loved that about her, falling in love with her culture like he had with Radhika.

My culture was officially in fashion and it started to change how I felt about my identity.

Maybe this change would have happened anyway as I got older and cared less about what others thought of me, but it was certainly a factor.

And it helped that I was in a serious relationship for the first time. My boyfriend (a white New Zealander) not only accepted me for being different, but he loved my personality, falling in love with my culture at the same time he fell in love with me.

Slowly, I began to see myself through his eyes, and the two of us even went on a backpacking trip through India.

To my surprise, the locals didn’t think I was Indian until I told them my name. Apparently, the lightness of my skin, the balayage in my hair, and the clothes I was wearing made me not look Indian.

It was something I would have loved to hear as a teenager, but now it just seemed wrong.

I had spent a lot of time trying to be less Indian to fit in, but now that I was in India, I didn’t fit in either because I wasn’t Indian enough.

I felt lost between my two cultures. I had abandoned myself trying to be simply British instead of British Indian. I knew I didn’t want to go on like that.

When I returned home, I decided I was fed up with that white-centric beauty standard, so I launched a body positivity movement to celebrate big noses called #SideProfileSelfie.

It went viral and suddenly my social media feed was filled with beautiful women with strong profiles, which helped me change my own definition of beauty to include big noses like mine.

For the first time, exactly 15 years after I was told I was pretty “for an Indian,” I saw myself as beautiful.

Around the same time, I used my writing to explore my identity. I had published two novels in my early 20s, and the protagonists were white, because I had never read a book with a brown-skinned heroine. But when I reached my 30s, I made sure that my novels featured British Indian women as protagonists.

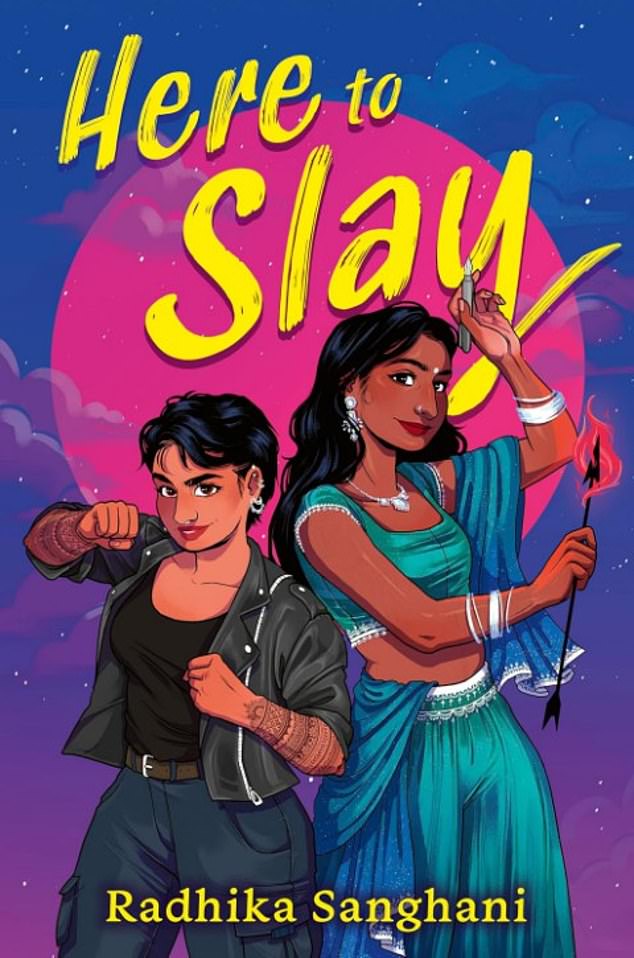

Radhika has now published a book called Here To Slay (pictured) for her teenage self, and on the cover her heroine, Kali, proudly wears traditional Indian clothing.

Now, I’ve published a book for my teenage self, which came out yesterday. It’s called Here To Slay and it’s inspired by Buffy The Vampire Slayer, except my 16-year-old heroine isn’t blonde; she’s British Indian, named after the Hindu goddess of death, Kali.

My Kali embarks on a journey to embrace herself in every sense: her skin color, her sexual identity, and her Indian origins, all while battling literal demons.

Most importantly, I made sure that the cover showed Kali proudly wearing traditional Indian clothing.

It has taken me a long time to fully love myself, but I refuse to ever feel ashamed of who I am again. I love the colour of my skin, my background and my identity, and I hope the next generation of young British Indian women never have to feel the way I did.

- Here to Kill by Radhika Sanghani (Knights Of, £9.99).

(tags to translate)dailymail