Table of Contents

Generation Z workers have flocked to the office, leaving many people bewildered and unsure how to deal with the often-woke young people.

Since the pandemic, young people have become increasingly reliant on the welfare state, as the Mail revealed earlier this year.

Generation Z is believed to include people born between 1997 and 2012, meaning anyone between the ages of 12 and 27.

A Deloitte report said: “Generation Z will soon overtake Millennials as the most populous generation on the planet, with more than a third of the world’s population considered Generation Z.”

He added: ‘As more Boomers retire, Generation Z will replace them, bringing with them a completely different worldview and perspective on their careers and how to succeed in the workplace.

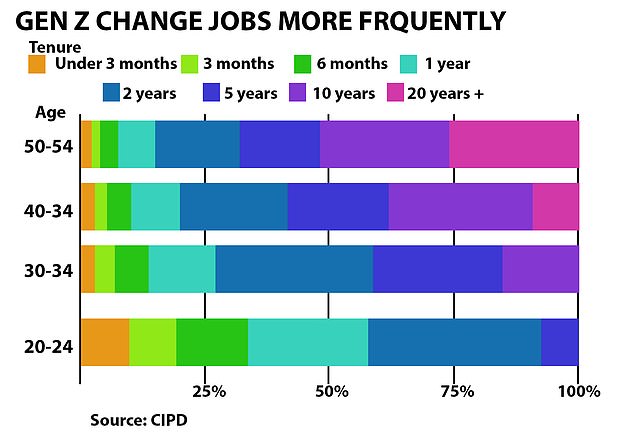

20- to 24-year-olds change jobs more frequently than any other generation

LinkedIn careers expert Charlotte Davies (pictured) said Gen Z workers may be less confident interacting with other generations while working from home during Covid.

“Understanding the forces that shaped their views, career aspirations and work styles is essential for companies seeking to attract them.”

Car leasing boss James McNeil, 38, said The Telegraph Working with Generation Z was a “nightmare,” as many were “afraid to talk on the phone” and thought “everything should be done by email or text.”

LinkedIn careers expert Charlotte Davies told MailOnline that Generation Z was the “fastest growing audience” on the platform.

She said: “Despite almost all professionals working in multi-generational environments, there seems to be a lack of communication between different age groups and professionals are falling into professional echo chambers – only talking to their peers and missing out on ways to push forward. his career”. .

“As a generation that entered the workforce in hybrid and remote work environments, Generation Z is missing out on informal observations and vital signs that traditionally guide behavior and collaboration, so it’s vital that employees actively engage with them on a regular basis. meaningful way.”

Here are her five tips on how to work with Gen Z professionals and one thing to avoid at all costs…

Provide professional development opportunities.

With four in 10 Gen Zers saying opportunities for growth and learning are the top priority when evaluating a company’s culture and values, it’s important for organizations to create an environment where they feel they can thrive.

Young professionals are well aware that they may not have jobs for life. They are much more likely to have ‘rolling careers’ and forge their own career paths, knowing that they will face many changes and upheavals with new technologies like AI, so invest in opportunities for them to develop professionally.

That could be learning and honing a new skill or exposing yourself to a new team or the business in general, for example.

Understand what motivates them and why.

It is well documented that Generation Z are strong advocates of work-life balance and have different attitudes towards work styles.

Consider taking a step back to understand why this resonates so much with you.

Many young professionals took their first steps into the world of work during the pandemic.

The focus was firmly on the importance of staying healthy and they learned to work from anywhere.

Car leasing boss James McNeil, 38, said working with Generation Z was a “nightmare” as many were “afraid of talking on the phone” and thought “everything should be done by email or message text” (File image)

Therefore, it makes sense that they value companies that promote work-life balance and offer flexibility in where they work.

This way of thinking will help promote understanding and break down outdated and unfounded stereotypes.

Create experiential learning environments

With most Gen Z professionals entering the workforce in remote and hybrid environments due to the pandemic, they are the least likely to feel safe interacting with other generations, although they recognize the importance of networking for their careers.

Encouraging interactive activities such as regular team brainstorming, face-to-face meetings, and open communication channels can help foster inclusivity.

By creating environments where members of Generation Z feel comfortable sharing their ideas and opinions, this will lead to more impactful collaboration and drive its development.

Additionally, consider inviting them to networking events and introducing them to your contacts, this way Generation Z can begin to build their professional network and gain confidence in this area.

Support the development of social skills

Our research shows that half of employees recognize that professionals who began their careers during the pandemic, predominantly Generation Z, need additional support to develop soft skills such as communication, leadership and empathy.

A total of 38 percent say they would ask another generation for advice about their career goals; Generation Z demonstrates an openness to learning, so helping to close some of the gaps left by the pandemic can show that you are on their side.

LinkedIn careers expert Charlotte Davies shared her tips for working with younger Gen Z professionals in the office (file image)

Try to open avenues to actively engage with your Gen Z colleagues by welcoming them into conversations and asking for their opinions and feedback.

Encouraging open communication in the workplace is beneficial for all employees and creates stronger teams.

With LinkedIn data revealing that communication is the most sought-after skill by UK employers, free resources such as LinkedIn Learning’s Communication Foundations can be a huge help.

Ask them to become your reverse mentor

LinkedIn data shows that Generation Z is the least likely to be contacted for advice in the workplace.

However, as the next generation of the workforce, your different attitudes and values are shaping the ever-changing world of work and it is therefore particularly valuable to engage with your perspectives.

Consider reverse mentoring: pairing younger employees with more experienced professionals to help fill potential knowledge gaps.

This relationship can help you stay on top of current job trends and also develop your own career, while promoting the development of skills such as leadership, communication, and networking for your Gen Z colleagues.

Make sure you commit to regular one-on-one sessions and set meaningful goals from the beginning.

Don’t dismiss the work values of Generation Z

Generation Z is more likely to say that other generations have misconceptions about their attitude toward work.

Try to leave your preconceptions at the door and take the time to appreciate that you entered the workforce at different and unprecedented times and, as a result, have different priorities.

Instead of getting frustrated, try to evaluate their prospects before writing them off.

This will best manifest itself through honest and open communication styles that facilitate active listening and reduce misunderstandings.

Additionally, look to support them when it comes to developing more traditional professional skills, such as time management and organization.

Because Generation Z values stability and transparency, they are willing and eager to receive instant and continuous feedback as this complements their desire to grow.

Instead of working against Generation Z’s distinctive approach to the world of work, harness their drive to improve by having regular check-ins with line managers that offer constructive, real-time feedback, as this will serve to keep employees engaged. Generation Z committed and motivated.