Ultra-processed foods, demonized for years for their supposed effect on our waistlines, don’t actually make people fat, according to an explosive report.

The US government’s top dietitians found “limited” evidence that these foods make people gain weight faster than any other food, after reviewing more than a dozen studies dating back to the 1990s.

The report has not been published in its entirety and only Segments have been uploaded. online.

But the snippets suggest that there is nothing intrinsic about processed foods that causes obesity and that the number of calories one eats is the most important factor in weight gain.

People have been hearing a lot about the health risks of ultra-processed foods recently, which might make this report surprising, Carolyn Williams, a registered dietitian who was not involved in the review, told DailyMail.com.

Previous studies have linked ultra-processed foods to cancer, diabetes, mental illness and obesity. According to the new report, the evidence that foods cause obesity is inconclusive.

The report comes from the U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), whose findings inform nutrition labels and public health recommendations for foods.

“What they are saying is not that there is no relationship between ultra-processed foods and greater body size or greater body fat,” Dr Williams told DailyMail.com.

“They’re saying that, at this point, we don’t have enough conclusive research to say that all ultra-processed foods should be avoided.”

This report comes from a group of 20 nutrition experts from across the country chosen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to draft new national nutrition recommendations. t

The current group has met to make recommendations for what Americans should eat between 2025 and 2030; this report will likely inform your new guidelines.

They recommend that more research needs to be done before rules can be established on ultra-processed foods.

The report has not yet been published online, but two slides were shared in a screenshot by Kevin D Hall, a nutrition scientist at the National Institutes of Health. in a publication

In its report, the DGCA said it had “serious concerns” about bias in studies that have linked ultra-processed foods to weight gain.

This is mainly because the definition of an ultra-processed food is not an exact science, meaning that studies may be subject to “misclassification bias.”

This means that studies that use variables that are difficult to categorize can lead researchers to draw inaccurate conclusions.

There is a system for classifying ultra-processed foods, called NOVA, that was developed by Brazilian scientists who began researching the issue in the 1990s. But there is a lot of “room for interpretation” in these guidelines, Dr. Williams said.

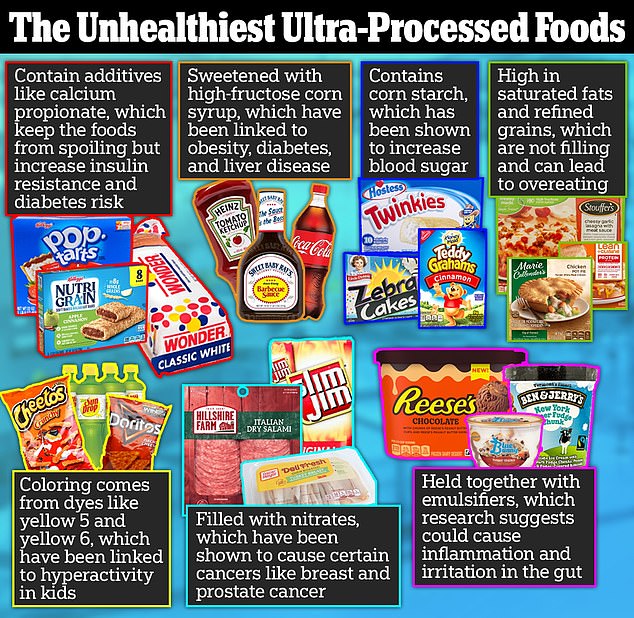

Generally, if a food has ingredients you wouldn’t use in home cooking (additives and stabilizers with long names, for example), then it’s probably an ultra-processed item.

This system does not classify foods according to the nutritional content they contain.

For example, mountain dew is ultra-processed, which has virtually no nutritional benefit, but so are many brands of multigrain bread, which contain fiber, vitamins, and even some protein.

This, according to nutritionists like Dr. Williams, calls into question the validity of ultra-processed food labels.

Dr. Carolyn O’Connor, a Texas A&M epidemiologist who previously worked at the Department of Agriculture and the National Institutes of Health, told the New York Times that certain types of UPF are much more harmful than others, so lumping them all together makes the measurement much less accurate.

Ultra-processed foods are the type of conspicuously packaged and aggressively marketed foods and drinks that fill our supermarket shelves (file photo)

‘Unfortunately this is valid. Until we have a definition of ultra-processed, the evidence will not provide a clear answer,” said Connie Diekman, a registered dietitian practicing in Missouri. he said in an responding to the conclusions of the DGAC.

Another problem the DGAC seems to have is that many of the studies they felt were robust enough to include in their review were conducted in other countries and only one study was conducted in a laboratory.

Without laboratory studies on a topic, it is difficult for scientists to conclude that ultra-processed foods are definitely causing health problems.

Some commentators counterattack the report, saying it doesn’t address many of the other concerns people have about processed foods.

Ultra-processed foods have been linked to type 2 diabetes, heart disease and mental health problems, a 2024 review by Australian researchers at Deakin University found.

The review examined older studies, covering about 10 million people in total, and found that ultra-processed foods could be linked to a number of poor health outcomes.

This study was valuable and increased Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health nutritionist Josiemer Mattei’s belief that ultra-processed foods could be a serious problem, he told The NYT.

The report also does not appear to address concerns that these foods have been linked to cancer.

A 2023 study from Imperial College London found that the more ultra-processed foods people reported eating, the more likely they were to develop all types of cancer.

Eating foods high in sugar and fat could dampen the effects of our genes that protect against cancer, according to a 2024 report from Singapore researchers.

It’s understandable that people read this part of the DGAC report and react angrily, Dr. Williams said. It doesn’t seem to be in line with what most people have been hearing recently, but it represents how science works, he said.

In his opinion, and that of many other dietitians, these foods have likely contributed to some of the public health problems we have been seeing in the U.S. But science is a slow process and the body of research is still has not “definitely” reached that point, he said.

The report simply highlights that further research is needed into ultra-processed foods.

He added: ‘This is really what you want. You don’t want your federal committee to jump to conclusions.