Australians’ living standards are stagnating, according to one of Australia’s leading economists, who shared new data showing the country has fallen behind other developed nations in a key economic area over the past 12 months.

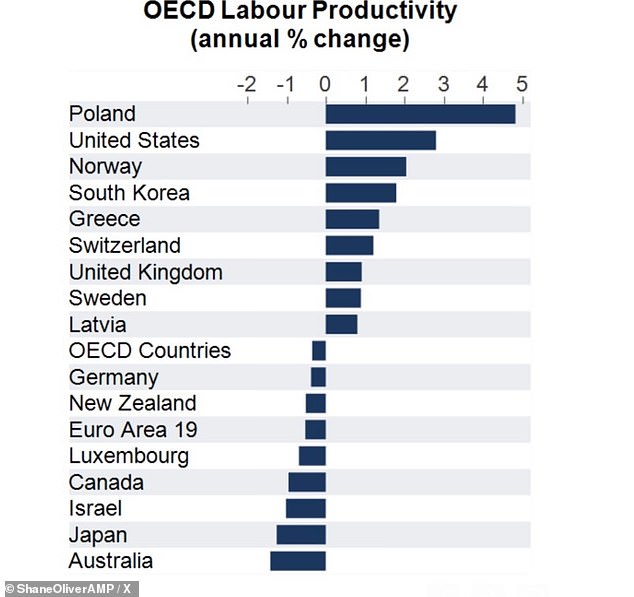

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver shared a graph on social media on Friday showing the change in labor productivity of more than 17 other comparable economies over the past year, with Australia ranked last.

According to Oliver data, Australia’s labor productivity, which is a generalized measure of how much output is produced per hour of work, has fallen more than 1 percent in 2024.

Other countries such as the United States and Norway had positive growth in labor productivity of around 2 percent, while Poland topped the list with a 5 percent increase.

Labor productivity can be used as an indicator of the standard of living in a country, since greater production generally means that workers are paid more and more is produced, making items cheaper.

“Australian labor productivity growth is at the bottom of the OECD… it is the basic reason why living standards are falling in Australia,” Mr Oliver said.

The economist said an increase in government spending was fueling the country’s falling productivity because it did less to encourage private enterprise.

“Rising public spending is exacerbating Australia’s productivity decline, with productivity falling a further 0.8 per cent over the past year, as private market sector productivity is invariably higher than public sector productivity.” and as public spending squeezes investment from private companies, it is likely to be exacerbating the weakness.” in the productivity of the private sector,” he explained.

A chart shared by economist Shane Oliver shows Australia is at the bottom of a group of developed OECD countries in terms of labor productivity growth.

Oliver said weak productivity growth has made inflation harder to control and hampers long-term GDP per capita growth, which in turn stagnates living standards.

He added that public spending was also making the RBA’s job more difficult as it had to keep interest rates high for longer because there was still high demand from consumers.

High interest rates were also “squeezing” private investment, he said.

“Federal and state governments need to reduce their spending to stop restricting private spending and do more to fundamentally boost productivity, which requires tax reform, labor market deregulation and competition reforms,” he said.

He said governments working with the RBA to reduce spending and control inflation was becoming more difficult with the looming federal election and the desire of both political parties to win votes.

Labor productivity is a measure of a country’s standard of living as it can show how much workers are paid and how much product is produced, which in turn affects the cost of goods.

Australia’s economy is still growing, but just barely, although economists are not convinced that weaker-than-expected data will trigger long-awaited interest rate cuts.

Full-year growth fell to 0.8 percent in September, down from 1 percent in June and below the consensus forecast of 1.1 percent.

Australian Bureau of Statistics head of national accounts Katherine Keenan said the country’s economy grew for the 12th consecutive quarter but has been slowing since September 2023.

Viewed quarterly, the bureau recorded a minor improvement, with the economy growing 0.3 per cent in the September quarter, down from 0.2 per cent in the three months to June.

Governments were once again large contributors to economic activity, with defense spending behind a sizeable 5.3 percent increase in public investment during the quarter.

Moody’s Analytics head of China and Australia economics Harry Murphy Cruise said cost-of-living measures, such as energy bill relief, took a chunk of what would normally be considered household spending and put it in the books of governments.

“That change, combined with tax cuts, freed up funds that could have been used on other goods and services,” he said Wednesday.

The Australian economy grew in the year to September, but only by 0.8 percent.

But households did not spend uncontrollably, but instead chose to accumulate savings reserves and pay mortgages.

“That kept household spending stable during the September quarter and pushed the household savings rate to its highest level since late 2022,” Murphy Cruise said.

As the Reserve Bank of Australia tries to engineer a slower economy to curb inflation by keeping interest rates high, the level of government spending has become a source of debate.

While some economists argue public spending is keeping Australia out of recession, others warn it is contributing to inflationary pressures and keeping interest rates high for longer.