Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, was frantic with worry.

On 16 October 1946, Wallis and her husband, the Duke of Windsor, the former Edward VIII, had left Ednam Lodge in Berkshire, where they had been staying with friends, to dine at Claridge’s Hotel in London.

In his absence, a daring raid was carried out on the house and Wallis’s jewelery worth up to £25,000 (around £1.3 million today) was stolen and never recovered.

It deeply affected both the duke and duchess.

WhatsNew2Day front page in October 1946 after the robbery

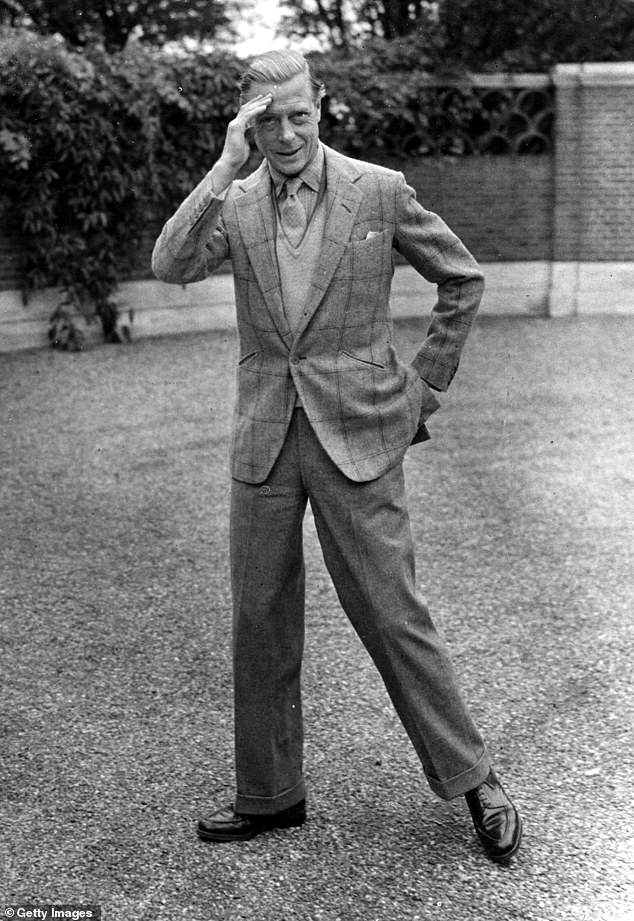

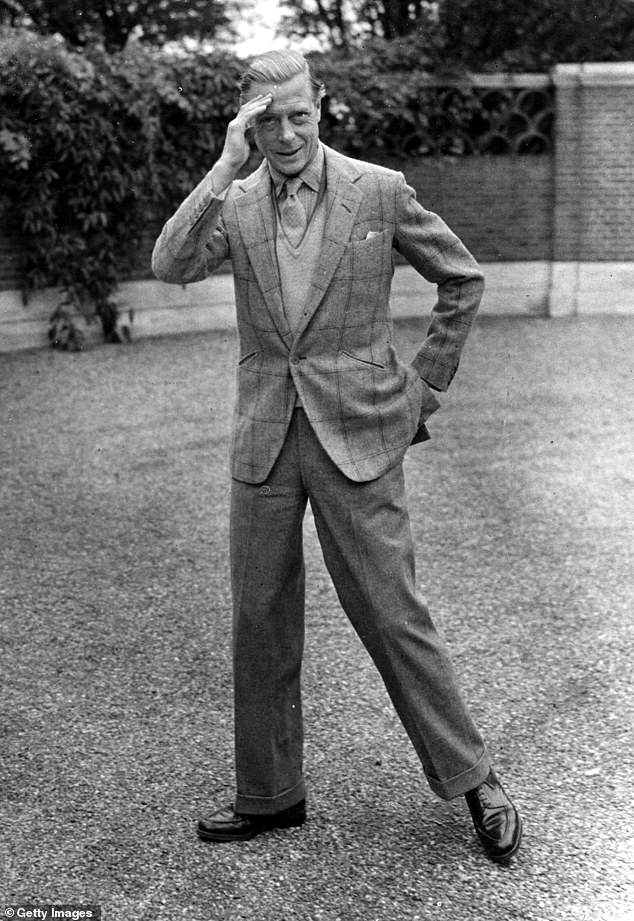

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were photographed in the grounds of Ednam Lodge, Sunningdale, the following day.

Despite the huge loss, the duke seemed happy and relaxed during the photo shoot.

Ednam Lodge, where the robbery took place in puzzling circumstances

Edward later wrote to his brother, King George VI, to describe his visit to Britain (he preferred to live in the United States or France after his abdication in 1936) as a “revelation” and mentioned that he had discovered “the bitter and costly that Britain is no longer the safe and law-abiding country it used to be.

On paper, it was a scandalous crime and one that remains a mystery to this day. No perpetrator was ever arrested.

However, there have been suspicions (both at the time and after Wallis’s death in 1986) that this burglary at Lord and Lady Dudley’s home was an inside job, carried out with the complicity of the cash-strapped Windsors. , or, alternatively, that the jewels were never stolen at all.

I explored this strange history in my new royal book, Power and Glory, and discovered a rich web of deceit, intrigue and wealth, relieved with some black comedy.

The first peculiarity was that, instead of placing the jewels in the locked vault of the house, they had left them in a box under a bed.

Although the Windsor detective was watching the room, the burglars were able to enter the house around six p.m., when the detective left for dinner.

The thieves are said to have climbed a long white rope that was tied to a window in Lady Dudley’s daughter’s bedroom and then walked straight into the Duchess’s bedroom, ignoring any other items of value there (or anywhere else). of the house) and they picked up the jewelry box and left, without being detected by anyone.

After Wallis’s maid, Joan Martin, raised the alarm, Ednam Lodge was thrown into uproar.

Due to the high-profile nature of the victims, Scotland Yard sent its Deputy Commissioner RM Howe and Chief Inspector John Capstick to the house.

When Edward and Wallis arrived, they behaved with almost exaggerated panic and anger.

In her memoirs, Lady Dudley later wrote of the Duchess that, although she was “in a bad state”, she demonstrated “an unpleasant and to me unexpected side to her character”, demanding that all long-serving household servants be ” dismissed”. through a kind of third degree.

The hostess refused, saying that “everyone except a cook [were] long-standing and dedicated staff.’

However, Wallis interrogated the maid as if she had committed the crime, despite the complete lack of evidence against her.

While Lady Dudley admitted that “they were both mad with worry and on the verge of tears”, this was not appropriate behavior for a duchess.

The next day, 18 individual earrings were found scattered around the nearby Sunningdale golf course. Much to Wallis’s annoyance, neither of them were a matching couple.

Boxes of Fabergé and a pearl necklace that had belonged to Queen Alexandra, the duke’s grandmother, were discarded as mere worthless trinkets.

A selection of the missing jewels was made and an impressive list resulted:

Rumors soon circulated that the jewels were worth up to £250,000, prompting Edward to release a statement saying: “There is absolutely no truth to the published statement that the value of the jewels was £250,000.” .

‘It was worth no more than £20,000 and you can say I said so. I can understand that the figure of a quarter of a million is a better reading than £20,000, but £20,000 was the value.

He told his American friend Robert Young that the crime was “a hard blow,” both because of the “substantial financial loss” and because “the sentimental and historical value of some of the objects is much greater.”

He suggested that “I haven’t yet given up hope of recovering parts of the loot, but we’re both feeling pretty sunk about it at the moment”, and blamed the press for making matters worse, saying that “the British tabloids haven’t spared us from taking out profit from our misfortune.’

The police were no help either. Inspector Capstick immediately decided, without any evidence, that the robbery could not have been an inside job, nor that the Duke and Duchess could have had anything to do with it.

Instead, he decided the perpetrator was a 27-year-old local man and petty criminal, Leslie Holmes.

Scotland Yard fingerprint expert Fred Cherrill, pictured, left, in the grounds of Ednam Lodge.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor photographed arriving in Dover in October 1946, a month before the robbery.

He became obsessed with trying to prove Holmes’ guilt, telling the FBI that “the police in this office know the identity of the thief and although, in 1950, he was released from a five-year sentence for burglary offenses, he did not We have done so, so far, we have been able to obtain enough evidence to accuse him of stealing the jewels of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

There is no doubt that he has buried the jewels and I am convinced that he is afraid to get rid of them.

He continued to harass Holmes, begging him to come clean.

For years, Capstick sent Christmas cards to Holmes, suggesting that the time had come to clear things up. As expected, he refused.

As his bewildered prisoner recalled in 2004: “He was a big, jovial guy, always quoting passages from the Bible. He was a very nice guy.

“I was offered a £4,000 reward for confessing and that tempted me. Sometimes I thought I should just put a cross on a map.

However, when Holmes spoke about the case, a possible solution was already in sight.

In 1987, Sotheby’s in Geneva held a sale of Wallis’s effects and at least 30 of the jewels that had allegedly been stolen were offered at auction.

Leslie Field, official historian of the royal jewelery collection, stated that: “I believe that the Duchess of Windsor defrauded the insurers by exaggerating the numbers and identifications of the jewels that had been discarded,” and that “from the beginning They had been in a safe in Paris and remained there.

A Cartier necklace was among the Duchess of Windsor’s treasure trove of jewelry sold at Sotheby’s

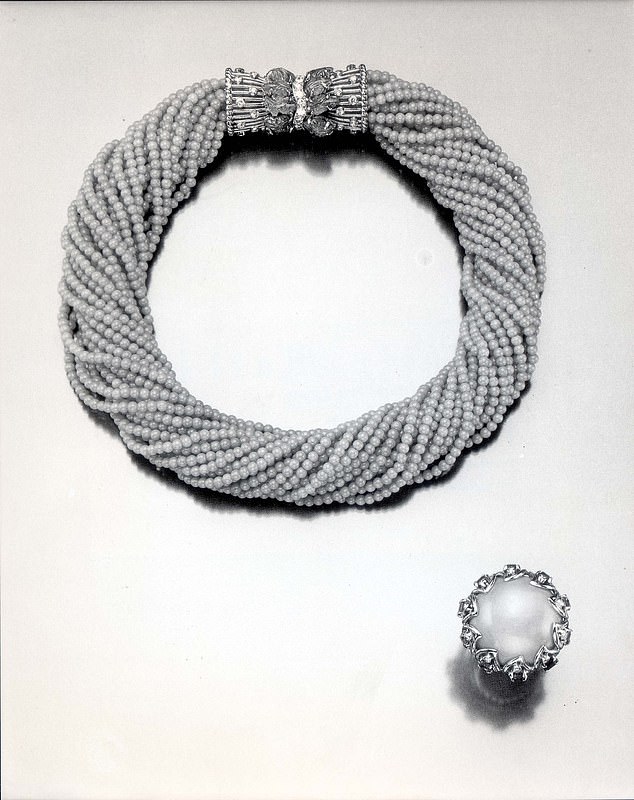

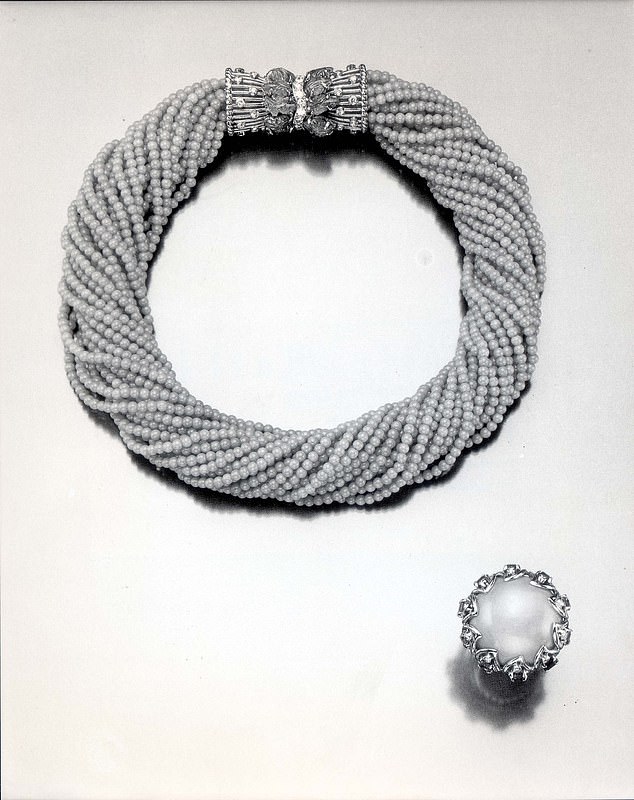

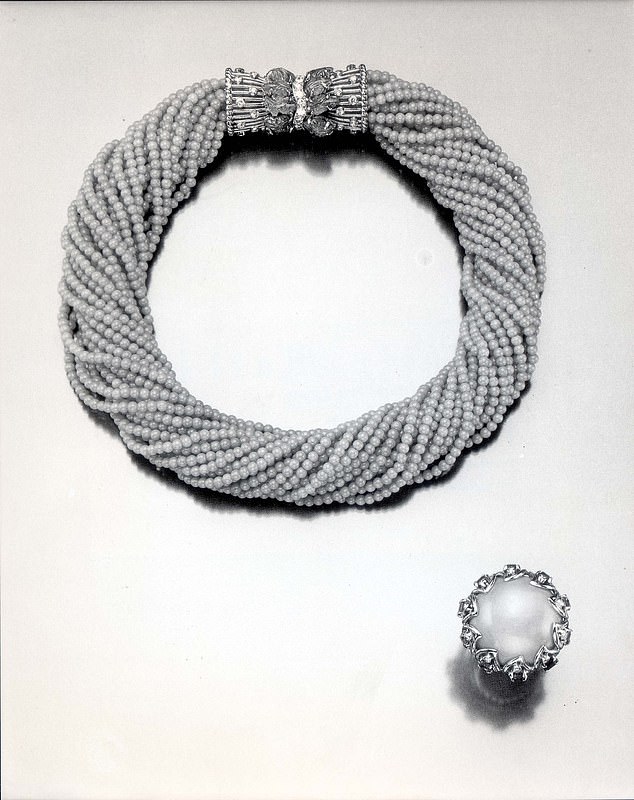

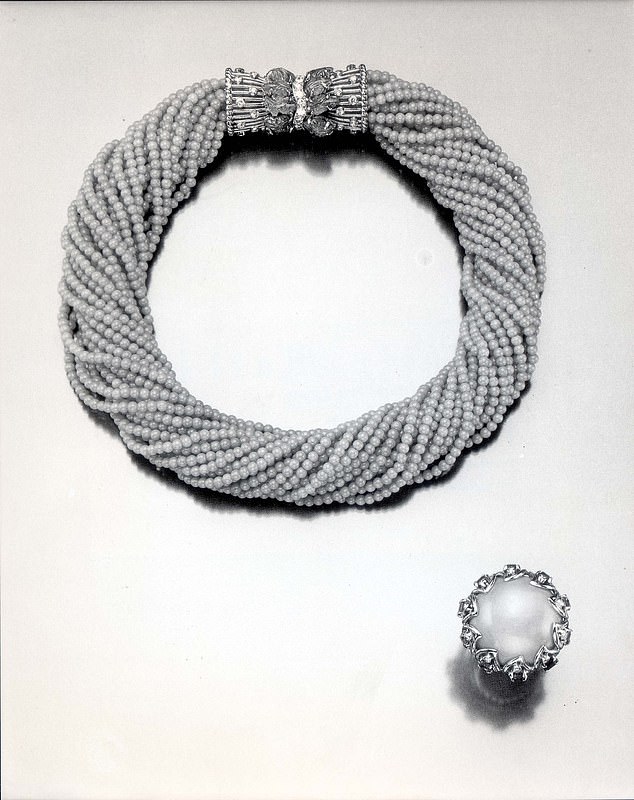

Some more examples of Wallis jewellery, later sold at auction. Gold, coral, emerald and diamond choker, by Cartier, designed as a skein of 24 rows of coral beads, on a tubular clasp, set with foliate motifs of cut emeralds and diamonds. And a cabochon coral ring, also by Cartier

The most charitable view is that a robbery had actually occurred, perpetrated by an unknown person or persons, and that Edward and Wallis capitalized on the crime to pocket the insurance money, exaggerating the losses for their own benefit.

The less generous view is that the Duke and Duchess had planned a fake robbery from the beginning, which would support Lady Dudley’s belief that Wallis’ show of indignation and anger seemed false.

Either way, it shows the most controversial royal couple of the 20th century in a singularly unflattering light, even if we will never know the definitive story of what happened that night at Ednam Lodge.

- Alexander Larman’s new book, Power And Glory – Elizabeth II And The Rebirth of Royalty, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, price £25