A 16th-century Italian “vampire” who was buried with a brick stuck in his mouth for fear of feeding on corpses underground has had his face reconstructed by scientists.

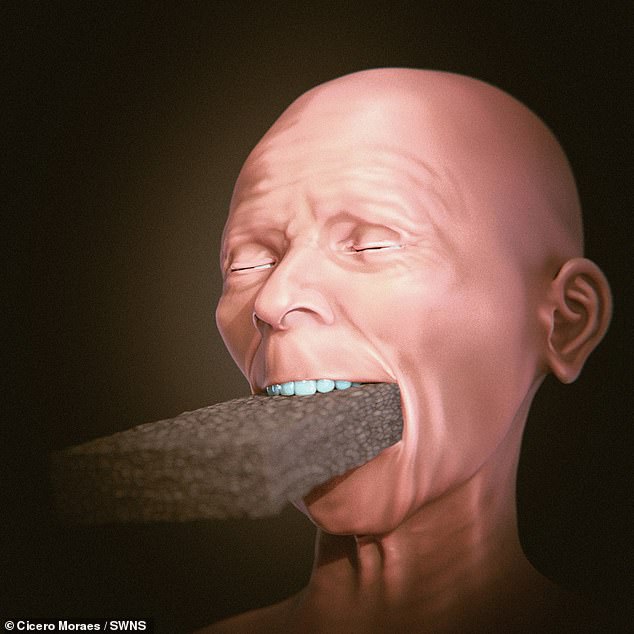

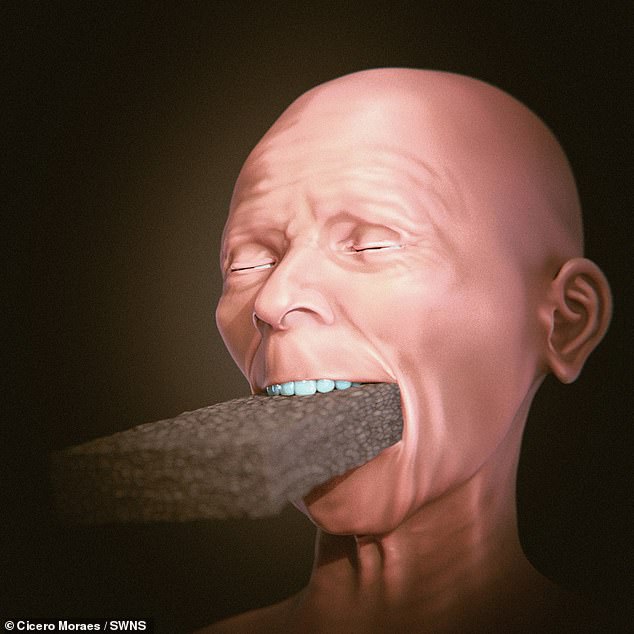

Incredible new images – made from 3D scans of her ancient skull – reveal a woman with a pointy chin, silver hair, wrinkled skin and a slightly crooked nose.

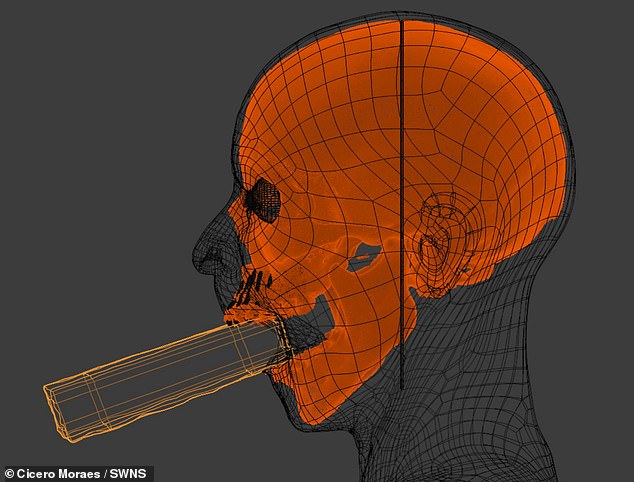

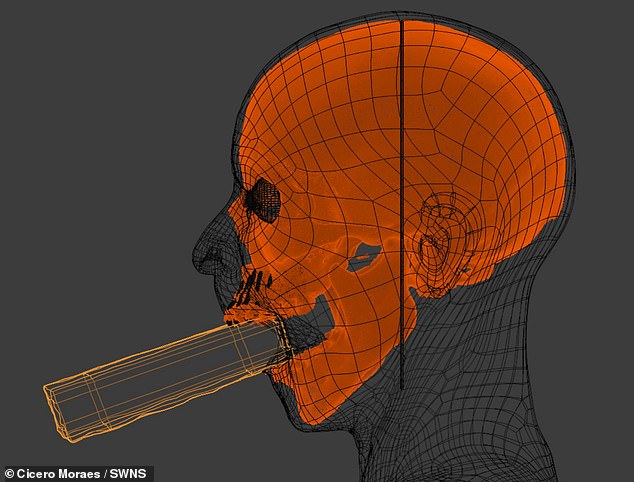

They also show what she would have looked like with the stone block inserted into her jaws.

Experts believe the brick was placed there shortly after her death by locals who feared it would feed on other victims of the plague that swept through an Italian town just minutes from Venice.

Skeletal evidence already suggests that she was 60 years old at the time of her death, but not much more is known about her.

The reconstruction of the woman’s face using 3D software made it possible to check whether a brick could have been inserted in her mouth.

His research also allowed him to test the theory that inserting the brick might even have been possible without damaging the mouth and teeth.

The astonishing reconstructions were carried out by Brazilian forensic expert and 3D illustrator Cícero Moraes, who detailed the project in a new study.

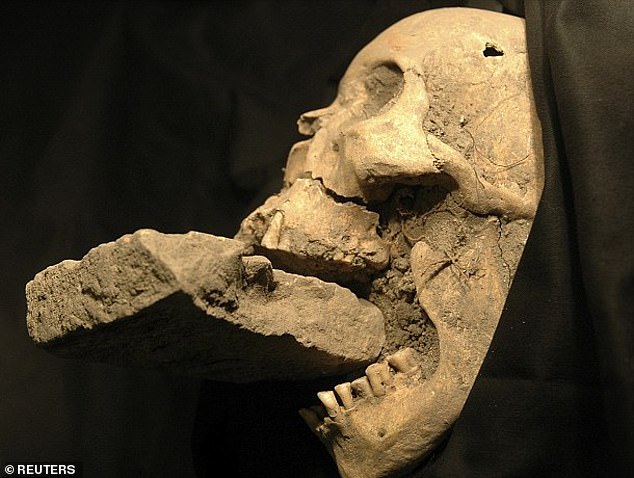

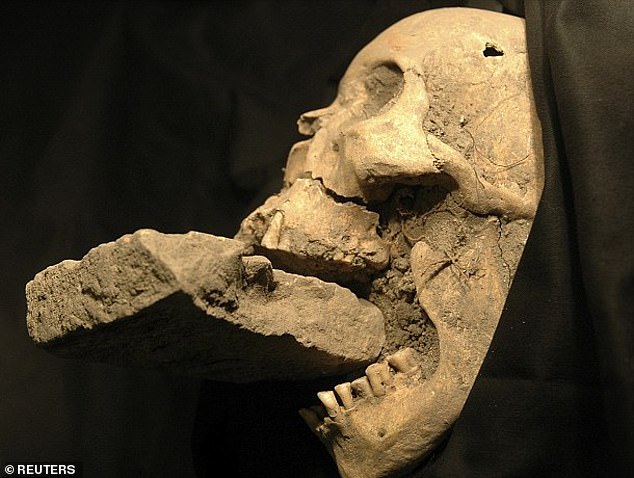

As Moraes explains, the skeleton was discovered in 2006 during excavations in the burial pits of Nuovo Lazzaretto in Venice, where plague victims who died between the 15th and 17th centuries were buried.

During the work, the skull from one of the graves attracted attention, because the jaw was open and inside the oral cavity was a stone brick.

“Studies were carried out to determine whether the positioning of the brick was accidental or deliberate,” Moraes explains in his article.

“The results rejected the first hypothesis, indicating that the placement of the brick was intentional and part of a symbolic burial ritual.”

Fear of vampires was widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages, largely due to a lack of understanding of why corpses swelled.

Belief in vampires led to rituals such as planting corpses in the heart before burying them.

In some cultures, the dead were buried face down to prevent them from rising from their graves, but objects in the mouth were another practice.

According to Moraes, the suggestion that the woman was considered a vampire dates back to a 2010 study published by forensic anthropologist Matteo Borrini.

“The anti-vampirism rituals we know today are the result of a historical evolution of the myth,” Moraes told MailOnline.

The remains of a 16th-century Venetian “vampire” buried with a brick in her mouth, allegedly to prevent her from feasting on plague victims.

Exploration of the mass grave from the 1576 plague epidemic resulted in one of the most bizarre archaeological discoveries. Now the pictures show what she probably looked like

In 2006, the woman’s skeleton was found in a mass grave of plaque victims on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Nuovo.

“The study specifically addresses the belief that inserting the brick prevented vampires from feeding and incapacitating them.”

Using 3D scans of the skull, Moraes estimated the distribution of soft tissue to flesh out the woman’s face.

Next, the nose was designed based on data extracted from measurements taken from tomograms of living individuals of different ancestors.

“Using all the projected information, it was possible to draw the profile of the face,” he explains.

His research also allowed him to test the theory that insertion of the brick would have been possible without damaging the mouth and teeth.

Moraes recreated the brick with Styrofoam cut to exact measurements to see if it would fit in his own mouth.

‘The original study contains some measurements of the brick, other images contain references to the thickness,’ Moraes told MailOnline.

“I cross-referenced data to generate a compatible sized brick and cut it from a piece of polystyrene which I painted to hold it firm.

“Then I tested the placement in my own mouth, with another person observing, because I wasn’t sure if it would work or not.

“It worked, so I transported the data to the 3D model and there too it was compatible.”

3D scan of the skull of the “vampire” woman in red with reconstructed tissue and the brick protruding from her mouth

Researcher Cicero Moraes recreated the brick using Styrofoam to see if it could fit in his mouth.

Researcher Cicero Moraes recreated the brick using Styrofoam to see if it could fit in his mouth.

Moraes says there are no surviving records from the woman’s life to suggest she was considered a vampire.

Instead, it comes from modern interpretations of why the brick was there.

It is already known that Lazzaretto Nuovo served as a quarantine station for plague victims from the 15th to the 18th century.

This coincided with a fear of vampires, sparked when locals noticed the corpses bloating as if feasting on flesh.

The skeleton of the “vampire” of Venice, however, is not the only one to have been found with an object in its mouth.

In 2014, researchers reported the discovery of the remains of a man in Poland with a stone in his mouth and a stake in his leg.

In Ireland, remains from the eighth century also had large stones in their mouths, placed there “violently”.