Rebel Wilson, the American actress and comedian, claimed that a member of the royal family invited her to a drug-fueled medieval-themed orgy at the home of an American tech billionaire in her new memoir, Rebel Rising.

Rebel stops short of naming the royals in question, but claims they were far removed from the line of succession and that the incident occurred in 2014.

The actress, 44, said she dressed in “a buxom damsel outfit complete with cone hat” and watched the “British royals stagger as [she] rose continuously [her] tits.’

She writes: “I was invited at the last minute to a tech billionaire’s party; the guy who invited me, who is fifteenth or twentieth in line to the British throne, had told my friend: ‘We need more girls”.

“The party was crazy. Men were jousting on horses in a field, girls dressed as mermaids were in the pool…

Rebel Wilson, the American actress and comedian, has claimed that a member of the royal family invited her to a drug-fueled medieval-themed orgy.

The actress, 44, made the claims in her controversial new memoir.

“The property was huge and because there was quite a bit of driving, people had been assigned rooms to sleep there overnight.

‘{..]There’s a huge private fireworks show and suddenly it’s 2am and a guy comes out with a big tray full of what looks like a ton of candy.

‘I thought, “Ooooh, is that candy?” and the guy holding the tray says, “No, this is the Molly [MDMA]”, and I turned to the screenwriter I had been talking to, confused.

“He says, ‘Oh, it’s for the orgy… orgies usually start this stuff around this time.’

He continued: ‘Now the Windsors’ comment about needing more girls started to make a lot more sense. They weren’t talking about a ratio of boys to girls like it was an 8th grade disco. They were talking about an ORGY!

“Needless to say, I lift up my damsel dress and run out of there as fast as I can.”

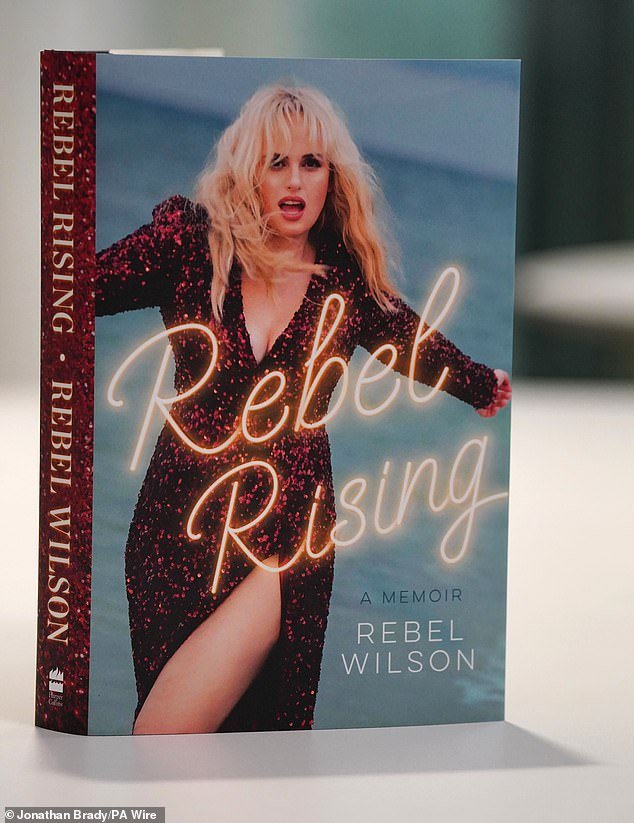

The memoir will be published in the United Kingdom on April 25 and has already created a wave of controversy in the United States.

The Australian actress originally claimed she was facing possible legal action after devoting an entire episode to a difficult work experience with an unnamed former co-star, branded a “jerk” by Wilson.

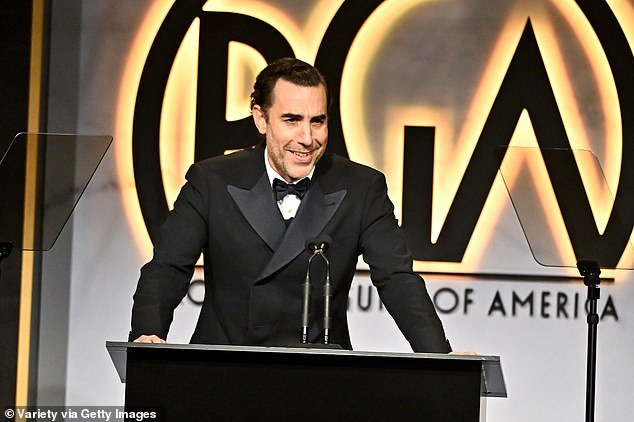

Sacha Baron Cohen broke his silence in March after Rebel Wilson claimed he is the ‘jerk’ she refers to in her explosive new memoir.

Rebel has named British actor and comedian Sacha as the celebrity responsible for making threats over his no-holds-barred memoir, Rebel Rising.

The post came two days after the Pitch Perfect star alleged that a celebrity she had worked with was threatening her over the publication of the memoir.

He has since confirmed that the actor in question is Sacha Baron Cohen, 52, best known for his comedy creations Ali G and Borat, with whom he starred in the 2016 action comedy Grimsby.

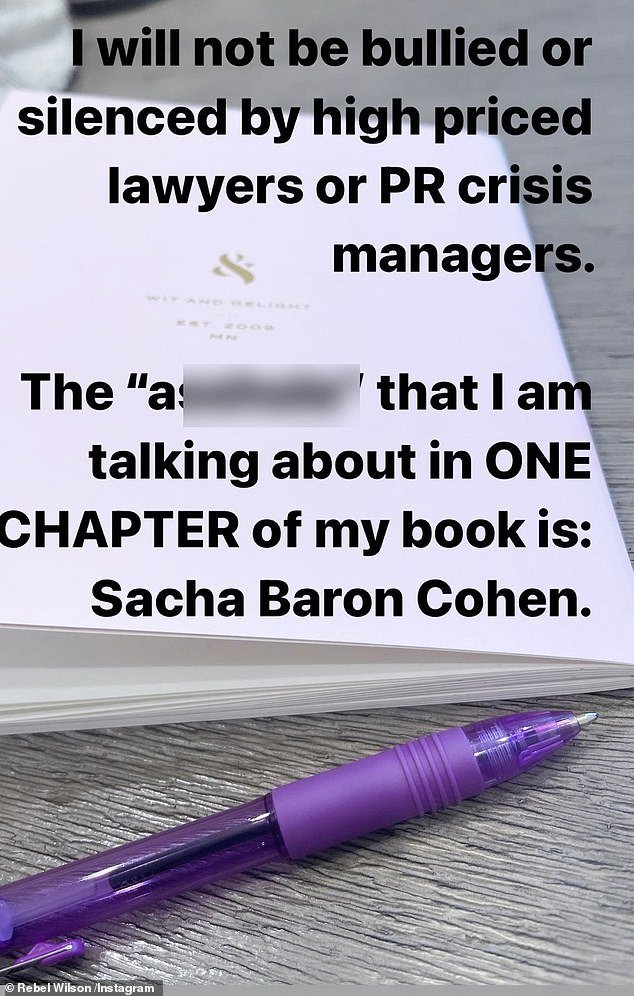

On Sunday she wrote on Instagram: “I will not be silenced by expensive lawyers or PR crisis managers. The idiot I talk about in ONE CHAPTER of my book is: Sacha Baron Cohen.

The post came just two days after the Pitch Perfect star alleged that a celebrity she once worked with was threatening her over the publication of the memoir.

“I wrote about a dick hole in my book,” he told his Instagram followers. ‘Now,’ he said, a ****** is trying to threaten me. He has hired a crisis public relations manager and lawyers.

He’s trying to stop the press from talking about my book. But the book will come out and you will all know the truth.’

Next, Sacha’s representative shared a statement with TMZwriting: ‘While we appreciate the importance of speaking out, these demonstrably false claims are directly contradicted by extensive and detailed evidence.

‘Including contemporary documents, film footage and eyewitness accounts from those present before, during and after the production of The Brothers Grimsby.’