Florida has become the center of a measles outbreak, with a seventh case of the virus confirmed Saturday.

The case is a child under five years old, the youngest infected in the outbreak so far.

It is also the first case identified outside of Manatee Bay Elementary School in Weston, near Fort Lauderdale, where the infection is known to have spread.

It comes as Florida Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo’s decision to allow parents to decide whether to quarantine their children or let them continue attending school has come under increased scrutiny.

Florida currently has the largest outbreak in the US, and there have been 35 cases in fifteen states in 2024 alone.

The cases “are not going to be limited to just that school, not when a virus is so infectious,” said Dr. David Kimberlin, co-director of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Florida Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo (pictured) allowing parents to decide whether to quarantine their children or let them continue attending school has come under increased scrutiny.

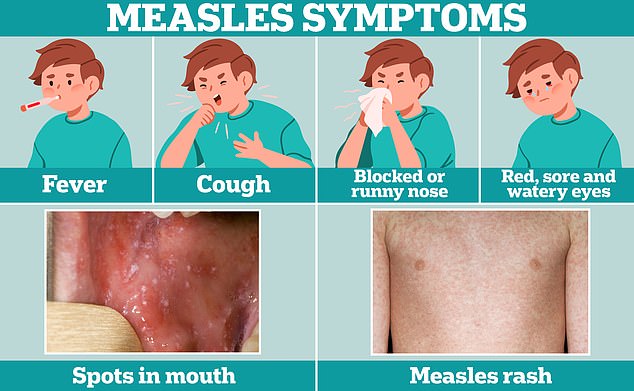

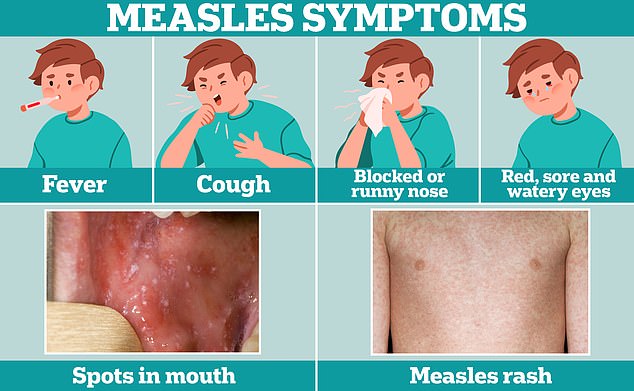

Cold-like symptoms, such as fever, cough, and runny or stuffy nose, are often the first sign of measles.

“Measles is the most infectious human pathogen we know of,” Kimberlin explained.

‘It’s like a heat-seeking missile. You will find people who are not immune and they will get sick.”

On Friday, Michigan recorded its first measles case since 2019.

Pennsylvania recorded nine cases of measles in January, eight of them in Philadelphia.

However, if no more cases are reported there by early next week, the outbreak will be declared over.

Unvaccinated people have a 90 percent chance of becoming infected if exposed, an issue of increasing importance as the use of vaccines such as MMR declines.

MMR vaccine coverage across the United States is below the safety goal for the third year in a row.

Coverage has fallen another two percent between the 2019-2021 school year and the 2022-2023 school year, according to the CDC, meaning approximately a quarter of a million kindergartens are at risk of measles infection across the United States. .

Measles is a highly contagious virus that is transmitted through the air and mainly affects children under five years of age.

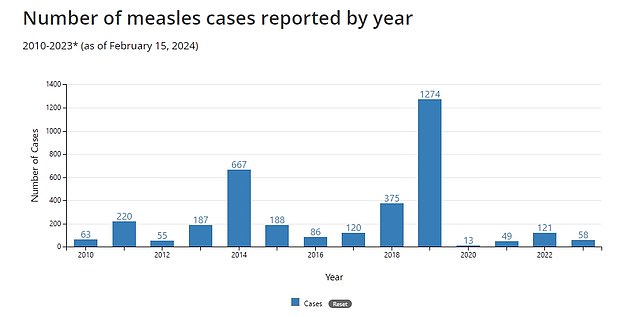

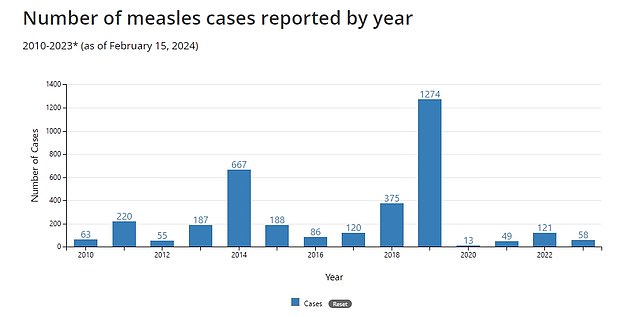

The above shows measles cases year after year in the United States.

The 93.1 percent rate during the 2022-23 school year is lower than the 95 percent rate in the 2019-2020 school year, leaving measles coverage below the national goal of 95 percent for the third year consecutive.

About 33 of 1,067 students at Manatee Bay Elementary School have not received either dose of the MMR vaccine, Dr. Peter Licata, superintendent of Broward County Public Schools, said Wednesday.

Doctors first learned of a case of measles (a third grader with no travel history) on Friday, February 16.

Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist and chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, told ABC News: “The lack of travel history in the measles cases suggests we are likely seeing local transmission, underscoring the serious risk to the community.” “.

“Measles is very contagious and due to its long incubation period of 11 to 12 days, there is a high probability that more children will become infected without showing symptoms yet.

“This situation is alarming and requires immediate public health intervention to prevent further spread.”

Measles is a highly contagious virus that is transmitted through the air and mainly affects children under five years of age.

It can be prevented with two doses of the MMR vaccine and more than 57 million deaths have been prevented since 2000, according to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The two recommended doses of the MMR vaccine are 97 percent effective against measles, the CDC reports.

One dose is 93 percent effective.

But measles vaccination rates have been declining, and more and more young children are entering schools unvaccinated.

Millions of people may not have received vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic, when health systems were overwhelmed and fell behind on routine vaccinations for preventable diseases.

If an unvaccinated child is exposed to measles, he or she should be given the MMR vaccine as soon as possible.

If given within 72 hours of initial exposure, the injection may offer some protection against measles or reduce the severity of the disease.