Book of the week: Paris ’44: The Shame And The Glory by Patrick Bishop (Viking £25, 400pp)

The Olympic Games are proving to be a wonderful showcase for Paris’s historic sites, as athletes from around the world race down its Haussmann boulevards and over its imposing bridges, passing Notre Dame, the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, the Luxembourg Palace, Les Invalides – one architectural gem after another.

It is strange then to realise that exactly 80 years ago, in the first weeks of August 1944, the inhabitants of the French capital lived in fear that all this magnificent and irreplaceable heritage was about to be destroyed, blown up and burned by German occupiers bent on revenge, now forced to flee as Allied forces closed in on the city.

An Olympic struggle of a different kind was underway, one of life and death.

British war historian and Parisian resident Patrick Bishop gives a vivid and moving account of how Paris came close to being devastated and many of its citizens massacred in a massive bloodbath.

Adolf Hitler with his right-hand man and Nazi architect Albert Speer, left, and German sculptor Arno Breker next to the Eiffel Tower in Paris in June 1940

Allied tanks and other army vehicles on the Champs-Élysées during the Liberation parade in August 1944, as crowds cheered.

We relive the tension of those days full of terror and, although we know the outcome in advance, it is a relief that the city emerges intact. It could easily have had a different, catastrophic ending.

Four years earlier, in 1940, Parisians had been shamed when their city fell to Hitler’s Nazis without a fight; their misfortune was compounded by their unbridled cooperation with their new masters, to the point of active collaboration in many cases.

It was more than a year before any kind of formal Resistance emerged, and even then it was irregular, disorganized and riven by political rivalries and suspicions, particularly between FTP communists and supporters of Charles de Gaulle, the irritable and self-centered head of Free France who had fled to England and whom many condemned for defecting to France.

August 1944, as the Germans began to retreat, was the opportunity for the French to counterattack, and for most of those who had been keeping their heads down – the atentistes, as they were known, those who were waiting – to jump on the bandwagon, “eager to redeem their mortgaged manhood,” as Bishop puts it, and pretend they had been holding out all along.

American troops marching down the Champs-Élysées in Paris with the Arc de Triomphe in the background

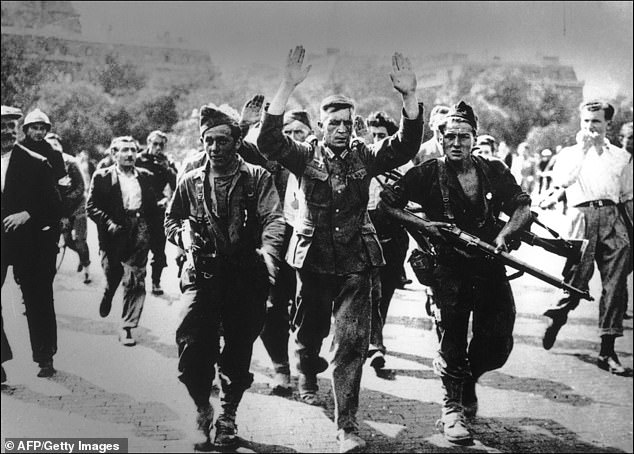

German soldiers surrender to French troops in August 1944 before the liberation of Paris.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill with French leader Charles de Gaulle in Paris in November 1944

But it was crucial to choose the right moment to take to the streets and man the barricades. On the other side of Europe, SS stormtroopers were ruthlessly crushing an uprising that sought to liberate Warsaw. If action was taken too soon, Paris could face a similar fate.

Amid the chaos and uncertainty, myths were created that endured. After the war, the German commander in Paris, General Dietrich von Choltitz, claimed to be the hero who saved the city by daring to defy Hitler’s order to raze it. And indeed, he had delayed, then negotiated, and surrendered, without pressing the destruction button.

But Bishop believes the general was stretching the truth, that he never had the explosives or the manpower to cause widespread damage and that his primary motivation was to save his own skin.

The real credit for Paris’s survival intact, the author argues, should go to the supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe, General Eisenhower.

The military plan, agreed from above, had always been to bypass the capital and concentrate all resources on forcing the enemy back to the German border. Paris was seen as a potentially dangerous distraction, slowing progress and jeopardising victory.

But Ike was discreetly shielded by the wily de Gaulle, who convinced him that leaving Paris to its own devices risked massive loss of life, anarchy and, worst of all, a communist takeover.

Against the orders of his superiors, the American undertook to ensure that de Gaulle could demonstrate his authority as the new leader of France. To this end, he agreed to have French troops, albeit backed by the Americans and the British, lead the liberation of the capital.

By mid-August, Paris was in serious turmoil, with strikes paralysing both the city and the police (who had been complicit with the Germans throughout the occupation but were essentially changing sides).

German tanks rolled down the boulevards, smashing through makeshift barricades. German snipers fired at random at people from rooftops. Anyone caught carrying weapons was shot on the spot.

Casualties mounted on both sides in what had become a people’s war, a popular uprising against the occupiers. However, they were vastly outgunned and barely surviving.

But salvation was on the way. Under the command of General Philippe Leclerc, the tanks and 16,000 men of the Free French Army’s 2nd Armored Division were approaching Paris. As they entered the city amid cheering crowds, those at the head of the column – most of whom had never set foot in Paris before – did not know the way to the centre.

A motorcyclist rode ahead and led them through winding streets to the Seine. It was 9.22pm on Thursday 24 August when Captain Raymond Dronne entered the Hotel de Ville to shouts of “Long live de Gaulle” and “Long live France”. Bells rang out all over the city, culminating in the grand peal of Notre Dame.

The Marseillaise, banned during the occupation, was sung on street corners. “We all had tears in our eyes,” recalled one soldier. “It was the sound of freedom, the sound of victory.”

But who won? When de Gaulle – radiating majesty and determined to take credit for himself – led the victory parade down the Champs-Élysées, he sidelined the communists of the Resistance and, in a speech, only nodded approvingly to the Allies, seeking their “help”.

Another myth was born: that France had been liberated. Although this was a parody of the truth, the past was successfully rewritten.

What happened next was anything but pleasant. Parisians turned against anyone they could make a scapegoat. Women who had slept with Germans were brutally treated – some 20,000 of them. Thousands of collaborators were summarily executed.

Bishop is scathing: “Few of his persecutors had done much to be proud of during the occupation. It is hard not to see this as an attempt to erase years of acceptance in an orgy of false righteousness.”

The subtitle of your book, “Shame and Glory,” is there for good reason.