The last surviving Nazi concentration camp guard has been declared unfit to stand trial, sparking outrage in Germany.

Gregor Formanek, 99, is accused of helping to murder 3,300 people at the infamous Sachsenhausen prison during World War II, known for its gas chambers and horrific medical experiments and executions used as a model for Auschwitz.

Formanek, from the Main-Kinzig district in the German state of Hesse, was due to stand trial for his role in the murders, but a court ruled that he is unfit to stand trial based on an expert assessment.

The expert considered that the former SS was unfit due to his advanced age and his alleged state of health, local media report.

The head of Nazi hunters at the Simon Wiesenthal Center said it is outrageous and very disappointing that Formanek’s case does not go to court.

He added that the perpetrator’s age does not diminish his guilt, and that Formanek has enjoyed the luxury of living to an old age, a luxury not allowed to the innocent Jewish victims and other enemies of the Reich whom he “murdered.” ‘.

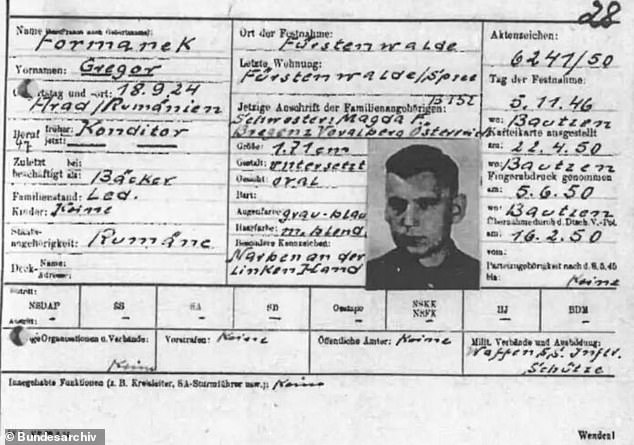

Gregor Formanek’s service as an SS guard is confirmed by a document from the SS Main Personnel Office.

Built in 1936 to house high-ranking political prisoners, Sachsenhausen is the camp where the Nazis perfected killing methods that were scaled up and used to murder millions in larger, more notorious camps like Auschwitz (pictured: prisoners at Sachsenhausen).

Pictured above is a roll call in the early morning or late afternoon in front of the gate of the Sachsenhausen Nazi concentration camp.

Formanek lived undetected for decades in a modest apartment near Frankfurt until journalists tracked him down last year, but the former camp guard remained silent about the allegations against him.

Incriminating documents from the Federal Archives and the Stasi Records Archive reveal Formanek’s horrific past.

Born in Romania, the son of a German-speaking tailor, Formanek joined the SS on 4 July 1943 and became part of the Sachsenhausen guard battalion in Brandenburg.

A Stasi document chillingly notes that Formanek “continued to kill prisoners.”

Holocaust survivor Jurek Szarf, 90, vividly recounted the brutal treatment of prisoners at Sachsenhausen.

Deported at the age of ten to Ravensbrueck with his aunt and mother, Jurek was later transferred to Koenigs Wusterhausen and then to Sachsenhausen.

His mother died of starvation in the Wusterhausen concentration camp in February 1945.

«I was with my father and my uncle in the Sachsenhausen hospital and they were going to shoot me. We waited for hours for the execution and then they released us,” Szarf told the German newspaper. image upon his release in April 1945, when he was 12 years old.

He was deported to Sachsenhausen from the other concentration camp where he was held a few days before being released.

Mr Szarf said: ‘The SS expelled the prisoners from Sachsenhausen on a long march to escape the approaching Red Army. My father, my uncle and I were too weak to march. Two other guys went with us. One was shot dead by SS guards and the other was beaten to death.

On his resume, Formanek omitted his role as a concentration camp guard, saying only that he was “called up for military service in Germany, where I spent 20 months.”

It is estimated that 200,000 prisoners passed through Sachsenhausen and that 30,000 people were murdered there, not including Soviet prisoners (pictured: some of the prisoners in the camp).

The infamous “Work Makes You Free” sign on the gates of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, photograph from the memorial service in January 2019

A dormitory for inmates at the former Sachsenhausen concentration camp, site of the Sachsenhausen memorial in Oranienburg, Germany

After reading the CV, Mr Szarf told Bild: “It does not mention Sachsenhausen. The SS guards insulted and beat us in the concentration camps. We were not human to them.

After the war, Formanek was arrested by the Red Army and sentenced by a Soviet military court to 25 years in prison for espionage and crimes against humanity.

Released after ten years, he moved to West Germany and lived quietly as a porter.

The local prosecutor’s office plans to appeal the decision that Formanek is unfit to stand trial, with the final decision to be made by the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt am Main.