Scientists scanned more than 13,000 creatures and revealed eggs inside a turtle, the ribcage of a bat and a rare stone snake that ate a centipede.

The project, called openVertebrate (oVert), was carried out by 18 institutions, which spent six years scanning specimens from museums with the aim of providing useful data for researchers to make more discoveries about the animals.

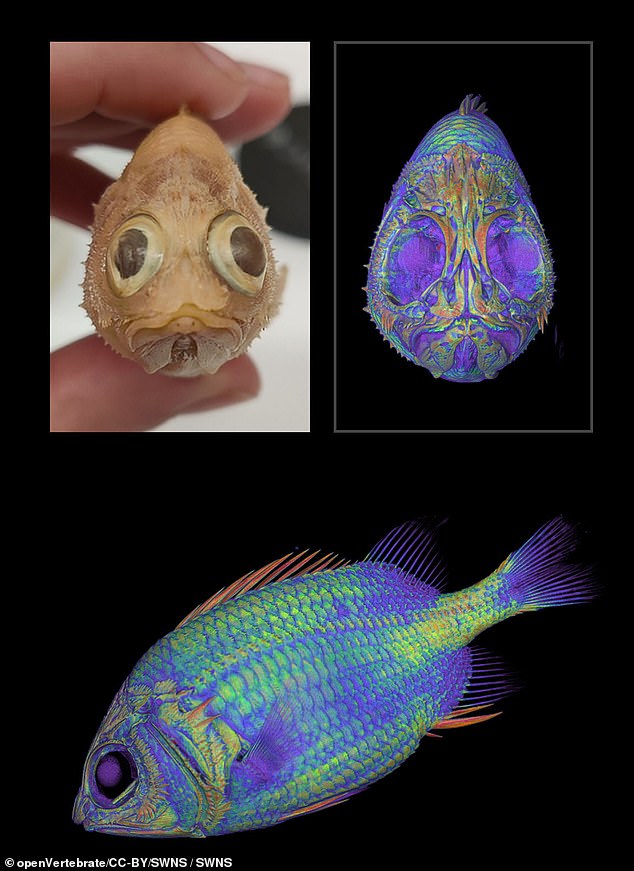

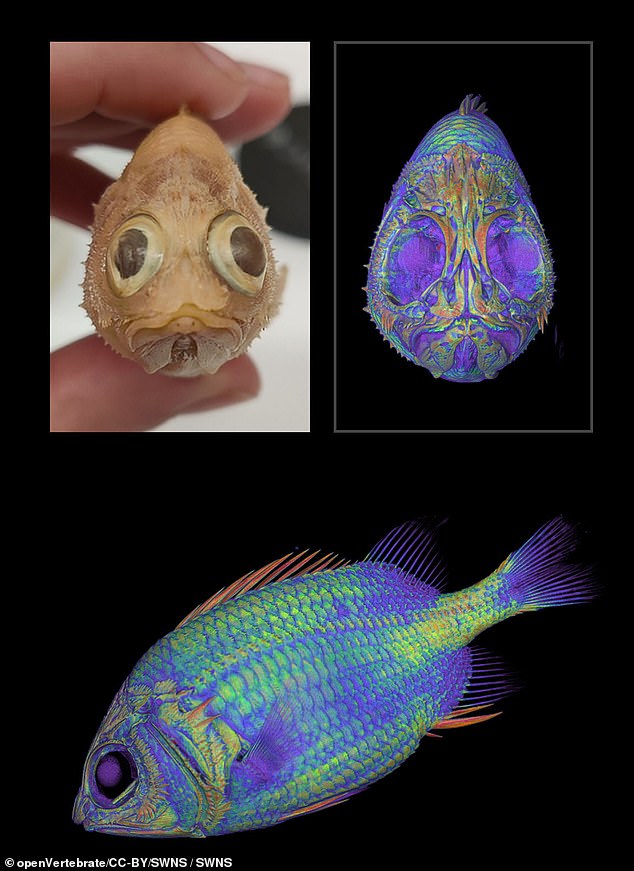

The team used high-energy X-rays to see through each specimen’s exterior, eliminating the need to dissect them, potentially destroying the creatures in the process.

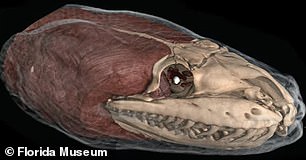

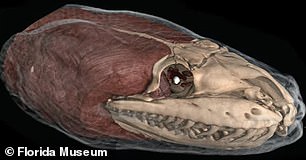

Scientists have already made discoveries using the scans, such as learning that a rare rock crown snake was killed while trying to eat a centipede.

Meanwhile, it also revealed that a dinosaur called Spinosaurus, which was larger than Tyrannosaurus rex and long thought to be aquatic, was actually a poor swimmer and would have stayed on land.

Researchers scanned 13,000 creatures, including amphibians, reptiles, fish and other mammals

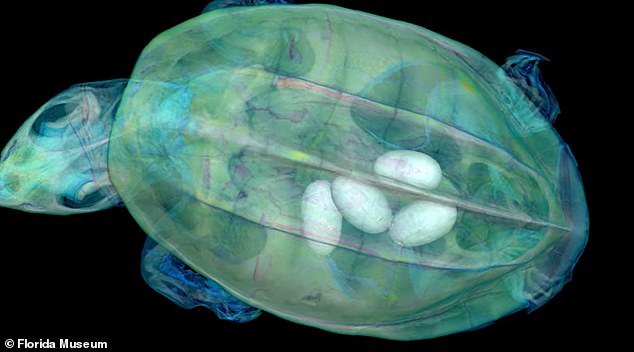

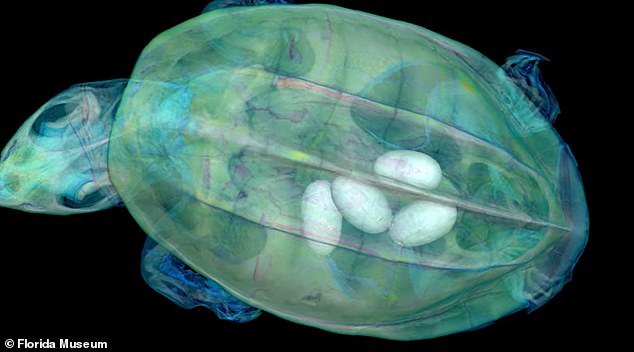

The 3D rendering of the turtle was difficult to get, so the researchers put it on a raft to get a full scan

Scientists scanned the creatures over six years, from 2017 to 2023

Previously this data could only be seen by scientists who traveled to see the specimen or if it was sent to them on loan, but now researchers and the public can marvel at the inner workings from anywhere in the world – and for free.

From 2017 to 2023, members of the oVert project took CT scans representing more than half of all amphibians, reptiles, fish and mammals in the United States

The research paper said that while they were able to obtain most amphibian and reptile samples, they are unlikely to make more progress for birds and mammals due to the lack of available samples in the US

“Museums are constantly engaged in a balancing act,” said David Blackburn, principal investigator of the oVert project and curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum.

“You want to protect specimens, but you also want people to use them.

“OVert is a way to reduce wear and tear on specimens while increasing access, and is the next logical step in the mission of museum collections,” he said.

A rare rock snake died while trying to eat a centipede

Scientists had to decide which specimens to use and have still only scanned about half of the creatures still locked up in museums

Researchers were able to collect most amphibian and reptile samples, but do not think they will make more progress for birds and mammals due to the lack of available samples in the U.S.

In some cases it was simpler to create a 3D rendering of the creature by running the specimen through the X-ray beam, but in other cases the project participants had to use their ingenuity to get a more complete picture.

Participants also had to decide which samples to use, and although the original goal was to scan only samples preserved in ethyl alcohol, some samples were too large for liquid preservation and the researchers did not want to leave them out.

Most 3-D models show before and after pictures of what the finished specimen looks like and its internal organs

The Idaho Museum of Natural History, for example, wanted to make a digital model of a humpback whale, but it was too large to get a clear image using the scanner, so instead they took the skeleton apart and scanned and produced a 3-D image of each bone.

When they were done, they reassembled the physical skeleton and the digital model.

These images are giving scientists better insight into how some of these creatures worked for the first time, including a model that revealed pumpkin toads’ fluid-filled canals in their ears had stopped working properly because they had become so small.

The OVert 3-D data has been viewed and downloaded by researchers, undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral scientists, collection managers, K-12 educators, and more

The OVert program is already being used by more than 3,700 people and the data has been viewed more than a million times.

Scientists have already made several discoveries because the 3-D models show details they couldn’t see before

The fluid channels trigger electrical impulses in the brain that help the frog identify itself from below, but because they stopped working properly, the frogs would crash when they jumped.

“All kinds of things jump out at you when you’re when you’re scanning,” said Edward Stanley, co-principal investigator of the oVert project and associate scientist at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Stanley was scanning spiny mice for the oVert project last year when he discovered that their tails were coated with internal bony plates called osteoderms, which were previously thought to be found only on armadillos.

“I study osteoderms, and through kismet or fate, I happened to be the one scanning the particular specimens that day and noticed something odd about their tails on the X-ray,” Stanley said.

‘It happens all the time. We have found all sorts of strange, unexpected things’.

Blackburn said it is important that people around the world can see these samples because it will not require them to travel to collaborate, adding that it is cost-effective in many ways.’

He continued: ‘Now we have scientists, teachers, students and artists around the world using this data externally.’

As of March 2024, the program is already being used by more than 3,700 people, and data generated by oVert has been viewed more than a million times.

The oVert 3-D data was viewed and downloaded by researchers, undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral scientists, faculty, collection managers, K-12 teachers, exhibit staff and more, according to oVert Research Article published in BioScience.

“It’s been a game-changer for my developmental unit,” said Jennifer Broo, a high school teacher in Cincinnati. Florida Museum.

Broo told the outlet that her students can become less engaged when they know things are fake, but by using the oVert models, ‘you can teach concepts at an appropriate level while maintaining the authenticity of science.’