Suddenly, tourism has become a dirty word, and tourists are feeling increasingly guilty about spending their hard-earned money and travelling to all corners of the world.

This is patently unfair, and particularly unfortunate given that we Brits are the best (and yes, sometimes not so best) tourists in the world, with an insatiable appetite for discovering new places and returning to old, beloved haunts.

Our climate helps, of course, but we are wedded to what Trollope called “the imperative duty to travel abroad.”

But what worries me is not so much the excess of tourism, but the obvious lack of vision of those who underestimate the mass exodus that occurs at this time of year, that infallible need to be somewhere else.

We Brits are the best (and sometimes not so best) tourists in the world, with an insatiable appetite for discovering new places and returning to old, beloved haunts.

Those who shoot water pistols at tourists in Barcelona or occupy beaches in Mallorca should aim their fire at the local politicians who have allowed total chaos.

Protesters hold placards in favour of reducing tourism during a demonstration in Barcelona

Rarely a week goes by without someone getting on their pedestal and complaining about “inhumane” security checks at airports, the chaos in departure lounges and a delay or two.

The good news is that those complaining have a choice: They can stay where they are and never set foot in an airport gate again, allowing the rest of us to enjoy the freedom that travel offers in all its forms.

My colleague Peter Hitchens – whose opinions I do not take lightly – wrote in these pages last week that he is “secretly ashamed” of being a tourist and prefers to call himself, somewhat grandiloquently, a “traveller”.

“Remember that the place you are visiting… is not a Disneyland created for your inspection and entertainment,” he wrote. “Try not to destroy what you have come to see.”

But if we all avoided mass tourism and headed instead to some of the places that have captured Peter’s imagination (such as Pyongyang in North Korea or the Kazakhstan capital Astana), there really would be a black hole in the UK’s finances.

Outbound tourism contributes around £80bn a year to our national coffers, including revenue generated by airlines, tour operators and travel agents, and supports almost three million jobs.

Amidst all the talk about economic growth, we should be promoting the tourism industry, not questioning it.

That’s a hefty £80bn, but listen up, Rachel Reeves.

Research by Advantage Travel Partnership, which represents independent travel agents, shows that on top of the basic cost of a holiday, we spend an average of £200 or more on related goods and services such as clothing, taxis, airport parking and the like.

Next year, the UK tourism industry (both inbound and outbound) is expected to be worth more than £257 billion in all its forms, around 10 per cent of our GDP. Today, it is not all about money, as it was in the distant and not so distant past.

In Victorian times, the Grand Tour of Europe was the preserve of a privileged minority, mainly male. Its purpose was to train the mind, provide a few relics bought at far-off flea markets and serve as a means for the sons of the aristocracy to have sex before marriage without causing a scandal.

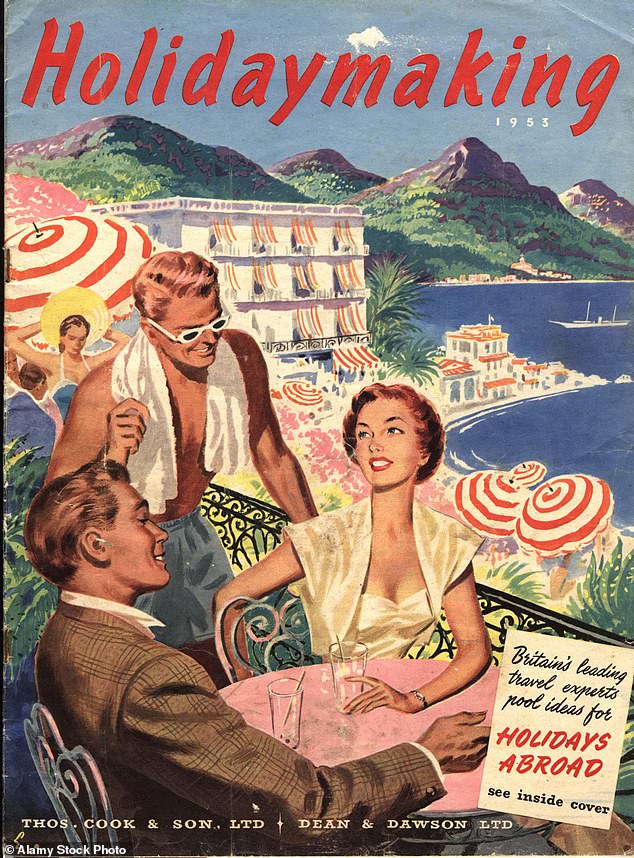

Thank goodness Thomas Cook introduced the first package holiday in 1851 (a trip to the Great Exhibition in London, with train, hotel and tickets included), but even in post-World War II Britain only the wealthy could afford to hop on a state-owned BOAC jet and enjoy a three-course meal before landing on the French Riviera, Barbados or Kenya.

And let’s not forget that the idea of being paid for a day off, let alone a week or two, is a relatively new phenomenon. It wasn’t until the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938 that a week’s paid holiday a year was recommended (but not enforced) for full-time workers. The beloved Sir Freddie Laker did his best to shake things up by launching the first “no-frills, low-cost” airline in 1966 and, although it crash-landed in 1982, the skies opened for companies like Ryanair, EasyJet, Tui and Jet2. It’s hard to think of a better example of levelling up.

According to aviation data analysts Cirium, almost 3,000 flights will take off from the UK tomorrow. Logistically, this will be a huge achievement, and we are likely to hear about any glitches in the system.

But what about the successes? I fly to and from Gatwick Airport regularly and have developed a fondness for the place. It may not have the architectural cachet of Singapore Airport or the Abu Dhabi Terminal, which cost £2.4bn and has become a tourist attraction in its own right, but, on the whole, it works.

Nearly 41 million passengers passed through Gatwick last year and that number is expected to rise substantially in 2024.

Contrary to what complainers would have us believe, getting through security at the newly remodeled North Terminal is almost always painless and the mood is full of anticipation of carefree days ahead.

I have even come to enjoy the meandering walk through the Duty Free, lined with dressed and groomed beauticians offering a spritz of some cologne or another.

Even at 6 a.m., they put on makeup like they’re ready for a wild night on the town (and that’s just the men).

No, I’m not ashamed of being a tourist. In fact, there’s nothing I like more. It’s a chance to be a different person for a week or two, a chance not so much to find yourself as to get lost.

It may all come to nothing once you get home and throw the same old trash into the same old bins, but vacations don’t just get you from point A to point B, literally; they can transport you from a tried-and-true reality into a world of new possibilities.

There is a philosophical answer as well as a geographical one to the question, upon returning from a vacation: “Where did you go?”

So sometimes holidays can be unsettling. They make us ask ourselves questions about ourselves that can be difficult to answer. The old saying “wherever you go, there you are” is inescapable, as is the person who looks back at me in the mirror every day – unfortunately, it’s me.

Of course there are concerns about tourism, but it is not the fault of the tourists.

Those who shoot water pistols at tourists in Barcelona or occupy beaches in Mallorca should aim their fire at local politicians who have allowed such madness, buying houses with the sole intention of renting them out, without regulation, at exorbitant prices, making them unaffordable for locals.

But let us not lose sight of the undeniable truth that tourism has lifted many countries out of extreme poverty, developed a solid infrastructure and contributed to improved health and education.

In fact, tourism is estimated to account for 10 percent of the world’s gross domestic product.

My older brother and I rarely travelled abroad when we were children. I think our parents, who married in 1950, considered it a bit vulgar, extravagant, even decadent. My grandparents thought so too.

They lived in the Scottish Borders but only came as far as Bournemouth for what my grandmother described not as a holiday but simply as a “change of scenery”.

The furthest my brother and I got was to the Isle of Wight, which at the time at least seemed like a different country because of the ferry ride.

If my parents were alive today, I’m sure they’d be in the “fast track” queue at Gatwick, although they might be annoyed at having to pay up to £90 for a bag in the hold.

Such are the rigors of modern life that getting away from it all has become sacrosanct.

During and after the pandemic, when people were asked what they intended to cut back on as the cost-of-living crisis worsened, very few said vacations.

All kinds of surveys suggest the same thing: holidays are the reason for many people’s lives. They have become central to our existence, a form of self-expression, a reaffirmation of family and friendship. A natural right.

What the hell is wrong with that?