Whether it’s a slow love song or an upbeat dance anthem, songs have a unique way of evoking emotions in people.

Now, scientists have revealed exactly where in the body different types of music are felt.

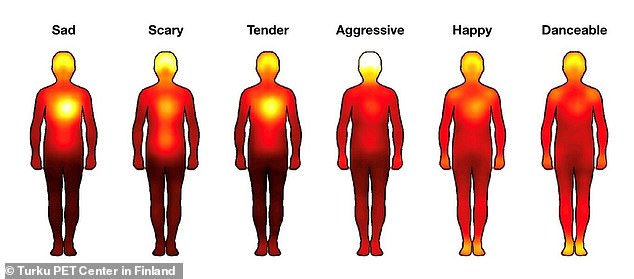

Unsurprisingly, sad songs evoke a response in the heart and the pit of the stomach.

Meanwhile, aggressive songs really get us worked up, according to researchers at the Turku PET Center in Finland.

“The influence of music on the body is universal,” said Vesa Putkinen, lead author of the study.

Scientists have revealed exactly where in the body different types of music are felt. Unsurprisingly, sad songs evoke a response in the heart and the pit of the stomach. Meanwhile, aggressive songs really get us hyped up.

Whether it’s a slow love song or an upbeat dance anthem, songs have a unique way of evoking emotions in people (stock image)

Music is often described as the “universal language that everyone speaks,” and previous studies show that when people from all cultures hear their favorite song, they can’t resist moving.

However, until now, little research has looked at how music evokes bodily sensations across cultures.

In their new study, the team recruited 2,000 participants, half of whom were from Europe or North America and the other half from China.

Participants were shown silhouettes of human bodies and asked to indicate which body region they thought would be activated in response to different styles of music.

The results revealed that different styles of music caused very different bodily sensations.

Sad or tender songs were felt in the head, chest, and pit of the stomach, while scary or aggressive songs were felt primarily in the head.

Meanwhile, happy and danceable songs were felt in the head and feet.

The researchers also found that the emotions and body sensations evoked by music were similar between Western and Asian listeners.

The researchers also found that the emotions and body sensations evoked by music were similar between Western and Asian listeners (file image).

“Certain acoustic characteristics of the music were associated with similar emotions in both Western and Asian listeners,” said Professor Lauri Nummenmaa, co-author of the study.

‘Music with a clear rhythm was found happy and danceable, while dissonance in music was associated with aggressiveness.

“Since these sensations are similar in different cultures, music-induced emotions are probably independent of culture and learning and based on inherited biological mechanisms.”

According to the researchers, the findings suggest that music may have emerged as a way to boost social interaction.

“People move to music in all cultures and synchronized postures, movements and vocalizations are a universal sign of affiliation,” said Dr. Putkinen.

“Music may have emerged during the evolution of the human species to promote social interaction and a sense of community by synchronizing the bodies and emotions of listeners.”