The remains of the world’s largest dolphin have been discovered in the Peruvian Amazon, revealing the mammal measured up to 11 feet long.

The remains of an ancient species distantly related to the rare and endangered river dolphin have been discovered in the Peruvian Amazon.

Paleontologists from Switzerland’s University of Zurich (UZH) found that fossils suggested the ancient creature was distantly related to the rare and endangered river dolphin, which lives in South America.

Fossils suggest that the recently discovered Pebanista yacuruna had poor eyesight, an elongated snout and many teeth when it roamed the oceans more than 16 million years ago.

The team named the new species in honor of the mythical people known as the Tacuruna, who lived in underwater cities around the Amazon basin.

The fossilized remains of an ancient dolphin believed to have lived 16 million years ago have been discovered in the Peruvian Amazon.

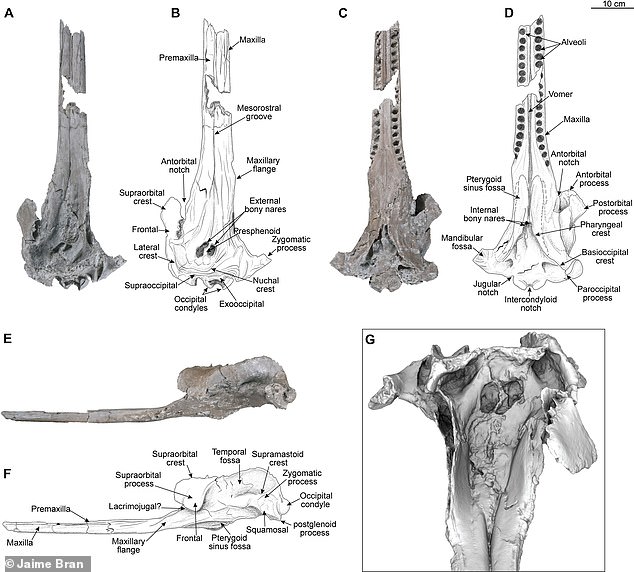

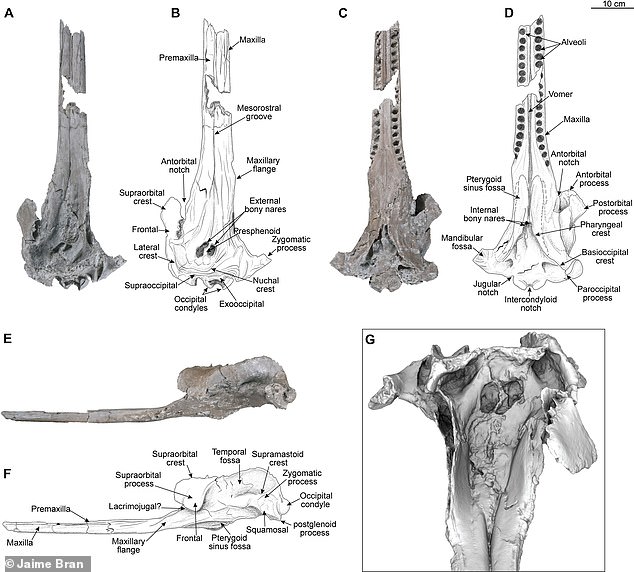

A team of researchers from the University of Zurich discovered the skull of the largest dolphin ever discovered

Researchers first discovered the dolphin’s skull during an expedition to Peru in 2018 when they saw the fossil protruding from the embankment of the Napo River.

The surviving river dolphins were “the remains of once very diverse groups of marine dolphins,” said Aldo Benites-Palomino. The Guardianadding that it is believed they left the oceans in exchange for freshwater rivers for food sources.

“Rivers are the escape valve… for the ancient fossil we found, and it’s the same for all river dolphins living today,” he said.

Back when ancient dolphins populated the oceans, the Peruvian Amazon had a very different landscape: it was covered in large lakes and swamps that covered Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Brazil.

Aldo Benites-Palomino first discovered the dolphin’s skull in a dike of the Napo River in Peru in 2018

According to researchers, climate change caused the demise of the Pebanista, as its prey began to disappear and the lack of a food source drove the dolphin to extinction.

About 10 million years ago, Amazonian waters flowed westward across the sandstone, forcing the lake’s remaining water to flow eastward.

Around this time, the large lake began to dry up and became a river, transforming the region from a wet and diverse ecosystem to a more arid and sparse region.

“After two decades of work in South America, we have discovered several giant forms from the region, but this one is the first dolphin of its species,” said Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, director of the department of paleontology at the ‘UZH.

“We were particularly intrigued by its particular and deep biogeographic history.”

Benites-Palomino said NewScientist that the area where he and his team found the fossil was once covered by an “incredibly large” lake, “almost like a small ocean in the middle of the jungle.”

The dolphin’s small eye sockets led researchers to believe it had poor eyesight, and Benites-Palomino told the outlet: “We know it lived in very muddy waters because its eyes started to shrink in size. “

Researchers found that the Pebanista had an elongated snout and many teeth, indicating that the dolphin fed on fish, like many other species of modern river dolphins.

Benites-Palomino and his team expected the dolphin to be closely related to today’s Amazon River dolphin, but instead found that the raised ridges on its head that aid echolocation make it similar to the dolphin river of South Asia.

Echolocation is an animal’s ability to “see” by listening to the echoes of its high-frequency sounds used for hunting.

“For river dolphins, echolocation, or biosonar, is even more critical because the waters they inhabit are extremely muddy, which hampers their vision,” said Gabriel Aguirre-Fernández, a researcher at UZH and co -author of the study.

Finding fossils in the Amazon is increasingly difficult because paleontologists must wait out the region’s “dry season,” when river levels are low enough to expose fossilized remains.

Collecting fossils is a time-consuming process because if paleontologists don’t extract them before the end of the dry season, rising river tides could wash them away and they could be lost forever.