Meghan Markle once told a business advisor that she had “legs up to a mile long” and that she wanted to show them off to get the best business advantage.

They are not its only strong point, as last week’s photos from the Canadian ski resort of Whistler demonstrated once again.

Never mind the all-American smile and careful dress sense, it is Meghan’s hair that could be described as her ‘crowning glory’, even if the Duchess is no longer a working royal.

Fans raved about the impeccably kept brunette locks on display, including Meghan’s “hairdresser to the stars” Kadi Lee from the Highbrow Hippie salon.

Color expert Lee revealed on Instagram that the duchess’ new look was due to a “blend of red and gold undertones” and “next-level high-gloss.”

Meghan’s ‘chocolate brown’ hair looked long and healthy on the first day at Mountain Square in Whistler

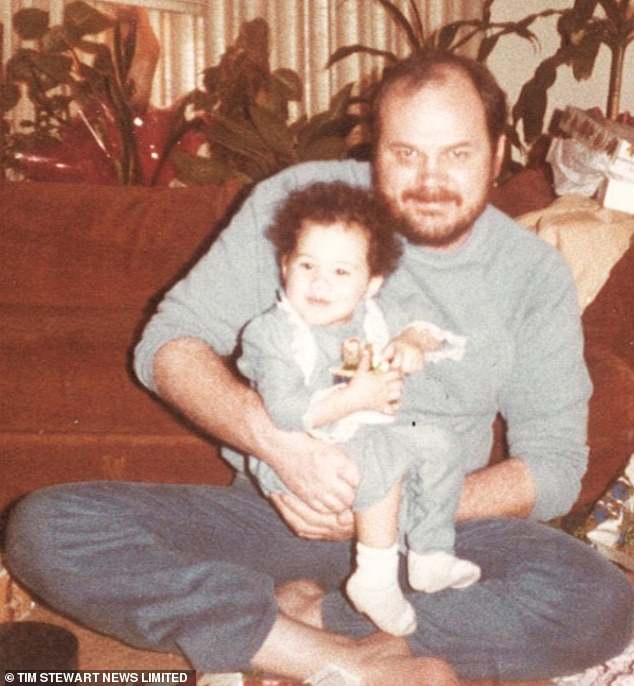

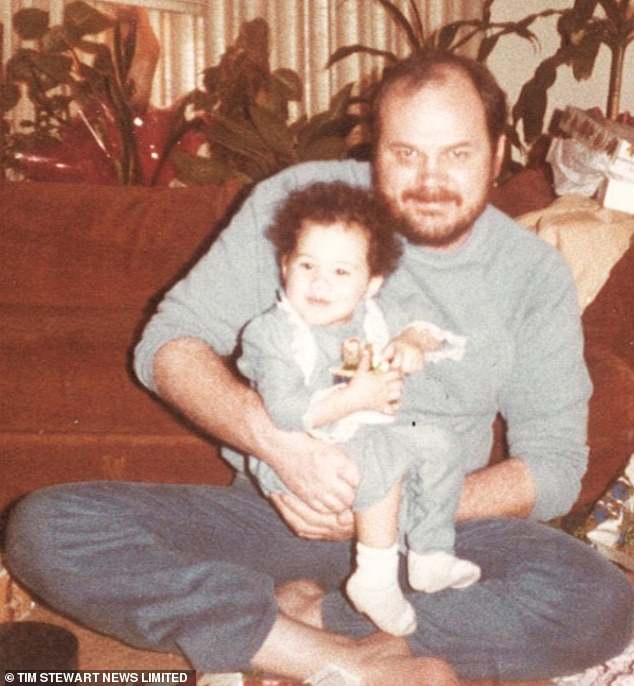

Meghan’s curly hair was a mix of her mother and father’s Dutch genes: Thomas, 79, got up at 5 a.m. every morning to help her straighten her hair with a straightening iron.

If Meghan’s hair has been an obsession throughout her life, as it is for many women, there is a “secret” that until now has not managed to transcend on social networks.

That’s the poignant role played by her father, Thomas Markle, who told me he sometimes got up at 5 a.m. to help his young daughter straighten her hair with a flat iron to make sure it looked exactly the way she wanted.

“When she wanted to straighten her hair, it would take her hours to do it before school,” she recalls.

“But it was something I did willingly.”

Tom, 79, once made his living as an Emmy Award-winning lighting director in Hollywood, but turned to amateur hairdressing when Meghan came to live with him after the breakdown of their marriage.

The duchess has not spoken to her father since he suffered two heart attacks on the eve of her 2018 wedding to Prince Harry and was unable to walk her down the aisle.

Tom says he was shocked to discover that his daughter’s hair exposed Meghan to racism at a young age.

During a vacation, father and daughter were driving across the United States from their home in Los Angeles to Florida, when they stopped in rural Texas and tried to find a salon to wash and straighten Meghan’s naturally curly hair.

“We tried several, but no one took us in because I was a white man with a mixed-race son,” he said.

When she became a ‘suitcase girl’ on the show Deal Or No Deal, Meghan adopted the signature shiny look we recognize today, using specialized treatments to soften and strengthen hair against damage.

Meghan still styles her own hair when necessary, often pulling it up into a sleek ‘ballerina bun.’

Once Meghan became a teenager, she learned to do her own hair and makeup, helped by spending time on set and in the studios with her father, a lighting director.

Tom recalls how Meghan studied and learned from professionals working on hit American shows, including General Hospital and Married with Children.

It was when she rose to prominence as an actress and became a Hollywood star (most famous as the “suitcase girl” on the show Deal Or No Deal) that Meghan adopted the signature shiny look we recognize today, using specialized treatments to smooth and strengthen the skin. hair against damage.

As he explained in 2011, it involves a fair amount of work and expense.

“My mom is black and my dad is Dutch and Irish, so my hair texture is densely curly,” she said. “I’ve been suffering from Brazilian blowouts for a couple of years.”

A Brazilian blow dry is a semi-permanent strengthening treatment that uses keratin (a key protein in hair and nails) to penetrate the hair cuticles and smooth the hair shaft.

Results last up to four months, but some salons in Los Angeles charge more than £400 ($500) per treatment.

Described by her stylist as “a dynamic shade of brunette, Meghan’s latest hairstyle worked well with skinny white jeans, a $675 (£530) white cashmere sweater and a beige puffer coat when she appeared in front of cameras last week .

The Duke and Duchess were in Canada to publicize the upcoming Invictus Games, hosted in Whistler, in a year’s time.

Created for sick and injured military men and women, the games were founded by Prince Harry, who organized the first event in 2014. Next year will see the introduction of winter sports for the first time.

Visiting a training camp, the couple met athletes hoping to participate next year and the prince was photographed “skiing”, joking: “Do I need to sign a waiver?”

If Harry received star recognition, Meghan’s hair, praised for its new reddish tint, came in second place.

‘This is the best her hair has ever looked!’ said one fan in response to the Instagram page of Los Angeles-based salon Highbrow Hippie, a favorite of Julia Roberts.

“Absolutely stunning,” said another. ‘So bright and healthy. GOALS.’

Meghan still styles her own hair when necessary, often pulling it up into a sleek ‘ballerina bun.’ It is also speculated that she wears high-quality hair extensions to add length and volume on special occasions.

In this, as in many other things, she has become quite an expert.

As one source said: “Meghan can do her hair and makeup at a professional level because, like everything she sets her mind to, she practiced and practiced until she was perfect.”