Today, former Labor opposition leader Bill Shorten will make his farewell speech to Parliament before his political career soon comes to an end.

He will take up the role of vice-chancellor of the University of Canberra.

While Shorten enters the political twilight, Anthony Albanese is planning the imminent election campaign, scheduled for before the end of May next year.

Shorten came very close to becoming prime minister but fell short when he lost what has been called the “unloseable election” in 2019 against Scott Morrison.

Shorten led every major opinion poll in the two years leading up to that election, including polls taken during the campaign itself.

However, the Labor Party not only lost the election, it went backwards. Undoubtedly, a major factor behind Shorten’s defeat was his high-target political strategy.

After Labour’s defeat, Albo took a very different approach. He pulled himself into a small ball and went to the 2022 election with the smallest of small-target agendas, having discarded almost every policy script Shorten had previously campaigned on.

The question arises: where would Australia be now if Shorten, and not Albo, had become Labor prime minister after the years of Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison Coalition government?

Would we be better or worse than now?

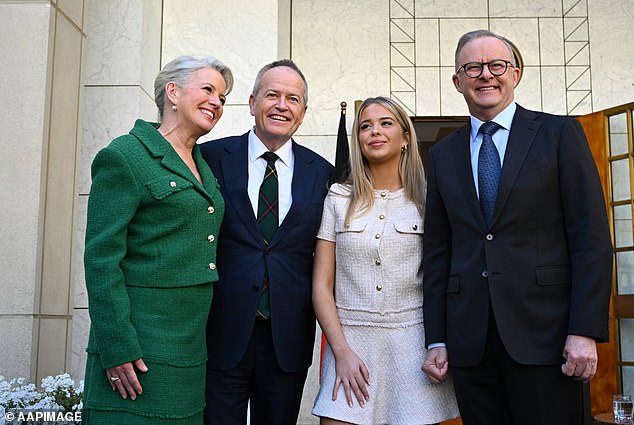

If things had been different, Bill Shorten would be the prime minister in the prime minister’s backyard, and Anthony Albanese simply a cabinet minister. Mr Shorten’s wife Chloe and daughter Clementine are above, first and third from the left.

For a start, Labor would have been in government before the pandemic hit, not immediately after.

And he would have won with a mandate for change, unlike the pyrrhic victory that Albo obtained, with no agenda or mandate in sight.

Shorten’s big plans included significant increases in government spending on health and education, along with major changes to the way the government collects taxes.

He pledged to introduce a new top marginal tax rate, limit negative gearing to new build properties and also wanted to limit franking credits on shares so they could not be used to receive a government credit where no tax had been paid. about income.

This final policy change created a huge backlash against the Labor Party among self-funded retirees.

Inevitably, some of Shorten’s agenda would have stalled or been modified in the Senate.

But with the support of the Greens it is very much possible if it had become law, especially in the context of winning an electoral mandate.

Economists are divided over the impact the policy changes would have had.

Some may have distorted markets, others had the potential to help with the cost of living and housing crisis we see today.

Anthony Albanese would probably be infrastructure minister (again) and his leadership ambitions would have been hampered.

Tanya Plibersek would not have been assigned to a secondary portfolio: she would have been deputy prime minister during the Shorten government.

The fact that Shorten had become prime minister less than a year before the pandemic struck may have limited the number of policies he would have implemented in a first term.

Remember: this would be Prime Minister Shorten’s second term at this point, had he won in 2019 and been re-elected three years later.

In addition, Albo would have been his infrastructure minister, the same position he held during the Rudd and Gillard years.

The rules of leadership probably would have prevented Albo from stirring the pot even if he had wanted to.

It is unlikely that Shorten would have plunged headlong into a Voice referendum campaign as Albo did.

It would have been much more pragmatic and cautious, avoiding the scenario we have seen where Indigenous rights have been set back decades courtesy of trying to impose a voice on Parliament when voters were not ready for it.

Shorten had committed to holding a plebiscite in his first term to determine whether or not the majority of Australians wanted a republic before moving on to debate models, if so.

Would the pandemic have put an end to that process? Maybe.

In an alternative Shorten universe, Treasurer Jim Chalmers would have been a much younger minister, although still in cabinet as finance minister. But it would not have been in Shorten’s inner sanctum.

Instead, Chris Bowen would be Treasurer and Tanya Plibersek would be deputy prime minister, rather than external, as she is now under Albo’s leadership.

She would probably be Shorten’s heir apparent, although Bowen and the right-wing NSW Labor faction might have had something to say about that when the time came.

So would Australians be better off or worse off if Shorten became prime minister?

It is difficult to imagine that we would be worse off, given the collapse in living standards and real GDP per capita under the Albo government.

That said, Shorten’s agenda implemented in full before the pandemic could have been a terrible time, causing all sorts of unintended consequences in the context of Covid.

Would Shorten have legislated important initiatives like JobKeeper? His instinct would certainly have been to do so, but would the Coalition in opposition have been as supportive as Labor was when Josh Frydenberg and Morrison did it? I have my doubts.

It would have been interesting to see whether Shorten could have improved his popularity with voters if he had been elected to high office.

His critics have long argued that his personal unpopularity was as relevant to the 2019 defeat as was the larger goal.

Perhaps the pandemic would have helped him achieve this, as was the case for state premiers such as Mark McGowan in Western Australia.

The 2019 election was a sliding-door moment for Shorten and Albo and, by extension, for the nation as well.