Among the tens of thousands of words about Chelsea’s chaotic start to the season, there is one significant element missing from the raucous discussion.

The incompetence at Stamford Bridge is an example of the worst that private equity can do. Ownership is vitally important to football clubs, as it is to all businesses, whether supermarkets, department stores or advanced aerospace and engineering firms.

Ownership is of crucial importance to football clubs, as it is to all businesses, whether supermarkets, department stores or advanced aerospace and engineering firms.

Private equity firms are often portrayed as a panacea for sclerotic and poorly managed publicly traded companies, and as a road map for amateurishly run sports teams.

But there have been a series of calamities and warning signs: Debenhams, Asda and care home provider Southern Cross. Chelsea fell into private equity hands in May 2022. The club had been seized by Her Majesty’s Treasury from Kremlin friend Roman Abramovich following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

By the standards of its baseball team, the Los Angeles Dodgers, when Todd Boehly and California-based Clearlake Capital took control of Chelsea for £2.4bn, the company was in good health. But all that private equity has brought to Chelsea is too clever accounting.

Incompetence at Stamford Bridge shows private equity at its worst

Chelsea looked to have a bright future in 2021 after winning the Champions League

The Boehly consortium is promising to spend £760m on replacing or improving Stamford Bridge (pictured) but so far little has been done and it is the least impressive of the top-flight club stadiums.

To avoid “fair play” rules that limit transfer spending, Boehly and company have turned to financial engineering. Instead of two-, three- or four-year contracts, players are on “long-term leases” of six to nine years, allowing their value to depreciate over the duration of the contract.

This is a clever calculation, but it also means that when mistakes are made, the players with the highest wages are the hardest to move on, and now the young lions born and bred at Chelsea are cannon fodder to be culled.

In 2021, under German manager Thomas Tuchel, the club became European champions. The future looked bright, with the Boehly consortium pledging to invest $1bn (£760m) or more in modernising or replacing Chelsea’s historic but comparatively small stadium at Stamford Bridge.

So far, little has been done. The stairs are narrow, steep and difficult to reach. The bathrooms are unhygienic. It is the least impressive luxury club.

When the team was a reliable, trophy-winning outfit, the shortcomings were tolerable. All this despite the fact that Stamford Bridge sits on one of the biggest and most valuable pieces of real estate. Abramovich had plans to invest £1bn or more in west London before he was ousted.

It’s easy to understand why so much faith was placed in Boehly and company. They turned the Dodgers from serial losers into World Series champions and developed a shiny new field at Dodger Stadium, despite it being the third-oldest stadium in Major League Baseball. They added business experience from the United Kingdom in the form of real estate magnate Jonathan Goldstein.

What could go wrong? Football is a notoriously fickle business, but generally a bottomless pit of money, stable ownership and skilled management and coaching yield trophies.

At Chelsea, the opposite has happened: a carefully constructed team of experienced and young players has been demolished and many of their best players are now at rival clubs.

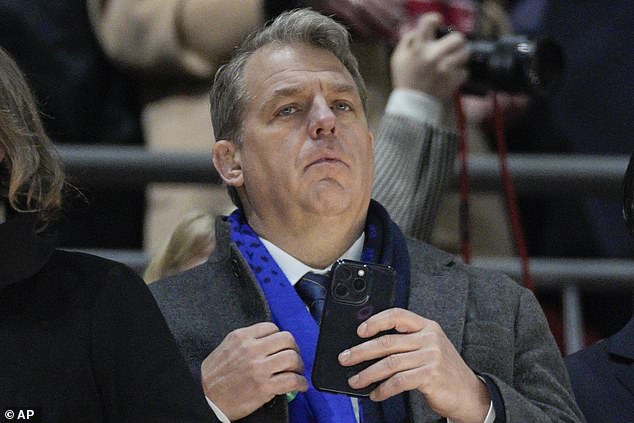

Enzo Maresca is the third manager in two years and Chelsea are eager to make a quick success of it

Conor Gallagher (left) has been transferred to Atletico Madrid, while Raheem Sterling (right) could be on his way out before the transfer window closes on Friday evening.

Instead of assembling a well-functioning team, the private equity owners embarked on a bizarre accumulation of a long list of potential stars, whose names most fans can barely recognize.

A £1bn transfer splurge has resulted in one of the most bloated squads in football history, with 54 players (at last count), eight of them on loan.

Instead of stability, they have brought the volatility of hedge fund investors to the club. The owners treat their main assets, the enormous talent of the established stars, with contempt.

Hard-earned, acquired players like Raheem Sterling and future academy talents like Conor Gallagher are being humiliated and traded away like objects rather than people after their breakout season.

Keen to make it big quickly, there is a third new manager in two years: Italian Enzo Maresca, 44, who joined from Leicester City with no direct experience of Premier League or European conquest. He replaced Mauricio Pochettino, who left by mutual consent, after securing a sixth-place finish in the 2023-24 season.

The patience of seasoned, intelligent fans with a deep understanding of the game and football finances has been tested. One of them, who has an acclaimed podcast, said he had “not turned on the TV for the first time in 20 years” for the season opener against Manchester City.

A lifelong fan and well-known lawyer and activist against racism in football wrote: “What a disaster.”

The rotation of players has left many fans asking for guidance for their own team from unknowns in the program rather than more easily identifiable visitors.

Pedro Neto is one of the latest additions to the Premier League’s most fan-filled squad

Chelsea appear to be a financially driven franchise on a path to self-destruction

Football has become increasingly scientific, analytical and statistical. Teams such as Brighton and Brentford have employed brilliant techniques, which have far exceeded their spending power, stadium size and international support.

But that mathematical precision only works when combined with specialized training, brilliant psychology and leadership.

Some 2,550 private equity tycoons in the UK benefit from a tax loophole known as “carried interest”. The sector defends itself by arguing that it employs millions of people and contributes greatly to the success of the City.

But there is a tendency to sweep under the carpet the negative effects in terms of wasted jobs, excessive reliance on debt and an ability to bypass good governance.

Chelsea shows the private equity scam at its worst, most culturally blind and indifferent.

It has provided the worst of both worlds in West London: a financially driven franchise on a journey towards self-destruction.