The mother of a boy with a severe peanut allergy has hit out at Manchester Airport after life-saving medication was allegedly confiscated during security checks.

Emma Wakefield, from Derby, was anxious at the thought of her son Ben, 14, going on a school trip as his allergies had hospitalized him in the past and left him seriously ill.

In preparation for her trip to Pisa, Italy, earlier this month, she packed two batches of medications, a paper prescription, a signed doctor’s letter, and a copy of Ben’s care plan.

He also wore a disability cord and was accompanied by a teacher. But at security, his medication was confiscated and allegedly thrown away, without staff first consulting his teacher.

In Italy, Ben had an allergic reaction to an apple, which was treated with a second batch of medication he kept in his suitcase.

Emma, from Derby, was anxious for her son Ben (both pictured) to go on a school trip to Italy earlier this month due to his severe peanut allergy.

Emma packed two batches of medication, a printed prescription, a signed letter from the doctor, and a copy of Ben’s care plan in preparation for her trip. Above: the couple appears together

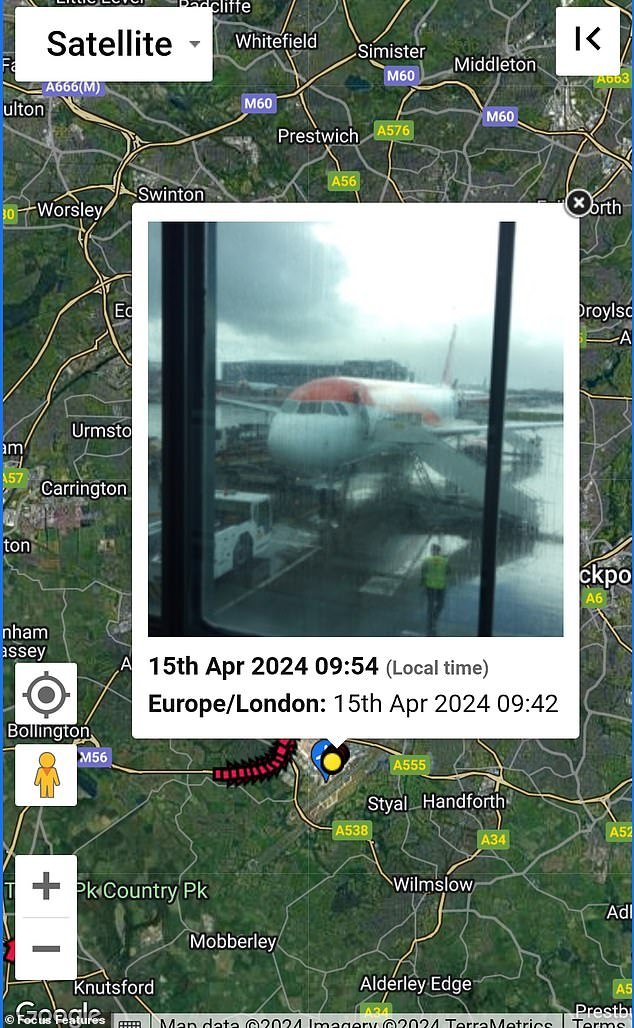

Emma claims security staff at Manchester Airport (pictured) confiscated Ben’s medication and ratted them out.

The 44-year-old mother said: “I was worried he would disappear due to his allergies so I followed all the instructions very carefully.”

‘The security worker did not consult with Ben’s teacher and did not consult his doctor’s letter or his care plan. He simply saw that Ben had too much liquid and spilled it.

‘That decision could have had tragic consequences. Ben took a flight without all the medications he needed and was at risk.

“In the past he was seriously ill in hospital due to allergies. His condition, and others like it, must be taken seriously. At a minimum, security workers should not make decisions for children without even letting their adult know.’

Ben’s condition was diagnosed at age two, after his arm swelled when he spread peanut butter on it. His condition was well managed, but at age 10 he suffered a severe reaction from a nougat bar.

The mother-of-two said Ben had been “extremely sick” in the past due to his allergies and was shocked to hear he had supposedly been taken off his medications. Above: Emma with her two children, Ben and Izzy.

Emma slammed the airport and said the alleged action could have had “tragic consequences.” Above: the mother photographed with her children Ben and Izzy.

Ben needed to take his medication after suffering a reaction to an apple on the trip to Pisa and luckily he had medication in his suitcase. Above: One of Ben’s vacation snaps.

He was rushed to the hospital by ambulance and placed in intensive care while doctors stabilized his condition.

Emma said: “There is no doubt they saved his life and it was a reminder of how serious it could be.” ‘When the school trip came, she wanted her to go have fun, but she was also worried.’

The mother-of-two said she followed Manchester Airport’s instructions when packing her teenage son’s medication.

‘I had packed two batches of medication, one in my carry-on and one in the hold, so if I had any problems at the airport or during the trip, I had my epi-pen and my antihistamine. She also had two inhalers,” Emma said.

At security, Ben and his teacher became separated and a security worker allegedly knocked over his antihistamine bottle.

The teacher explained: ‘Like most 14-year-olds, Ben made no complaints. They made no effort to talk to his teacher and he just moved on. An airplane is a high-risk environment for Ben, there is little ventilation and there are people eating in close proximity.

Emma claimed she followed Manchester Airport’s instructions when packing her son’s suitcase. Above: the mother photographed with her children Ben and Izzy.

Ben and his teacher separated during security checks and allegedly took away his medication. In the photo: the plane in Manchester before take-off.

Natasha (pictured), who had a fatal nut allergy, died on board a flight in 2016 after eating something containing sesame seeds.

“It’s terrifying to think he made that trip without proper medication.”

In 2016, a 15-year-old girl died on board a flight after suffering an allergic reaction to a Pret sandwich.

Natasha Ednan-Laperouse had a fatal nut allergy and was traveling with her father and friend to Nice on July 17, 2016.

Her father Nadim shared a baguette of artichokes, olives and tapenade with Natasha just before boarding the British Airways flight, but within an hour he lost consciousness and went into cardiac arrest.

The chain store had not labeled its packaging or revealed that the sandwich contained sesame seeds, a fatal ingredient for Natasha.

Her father Nadim shared a baguette of artichokes, olives and tapenade with Natasha just before boarding the British Airways flight, but within an hour he lost consciousness and went into cardiac arrest.

He said: “You can’t imagine having a small amount of something and having your child die in front of you.” It’s simply unthinkable.”

After her horrific death, Natasha’s Law was unveiled, a rule requiring food chains to include adequate warnings about allergens.

Emma complained at Manchester airport, but they claim their worker “was right to throw away the item”.

In their response to Emma, they said: “I understand your concerns regarding the medication, unfortunately we cannot allow it in hand luggage as per DfT directives, details and operational procedures we must follow, and I apologize for any inconvenience this causes. has caused.” caused you. ‘

Emma said: “I would like reassurance that this will not happen again.” I want them to change the procedure in the future so other children aren’t at risk like Ben was. Next time, his mistake could be fatal.

A Manchester Airport spokesperson said the incident is under investigation.