The United States is headed for another year of bloody gun violence; So far this year, more than 80 people have died in mass shootings.

New data from the Gun Violence Archive shows that 81 people have died in mass shootings in less than two months of 2024.

This year there have been 49 mass shootings, defined as an incident with four victims shot, either wounded or dead, not including the shooter.

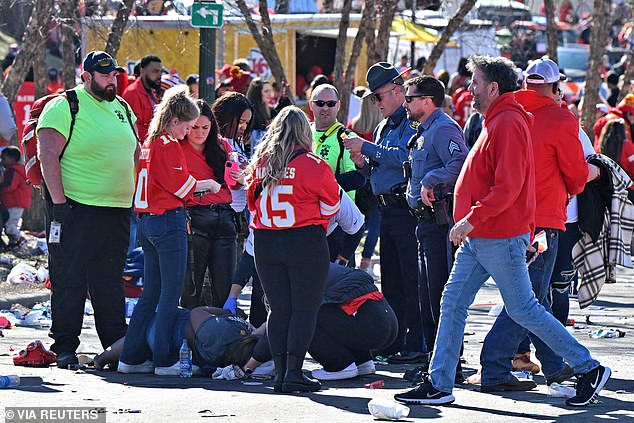

The latest tragedy occurred when one person was killed and more than 20 injured after a gunman opened fire at the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl parade, where thousands gathered to celebrate the team’s victory over the 49ers. from San Francisco.

Lisa López-Galván, a mother of two and disc jockey for a community radio station, died in the attack.

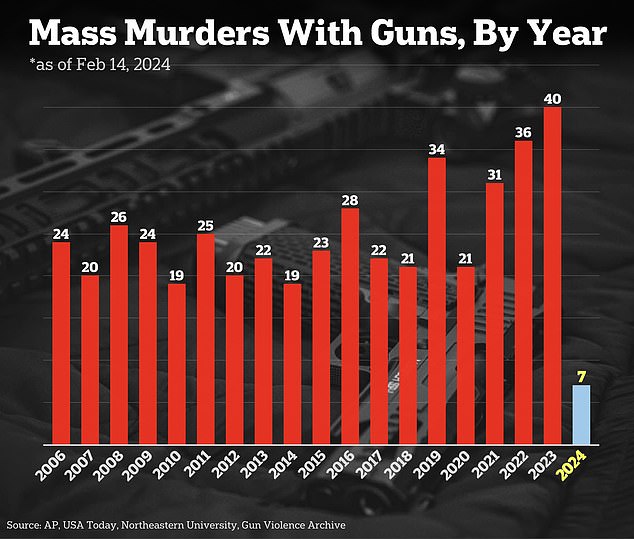

There were 40 mass murders with firearms in 2023. Less than two months into 2024, seven have been reported

Data from the Gun Violence Archive shows that 81 people have died in mass shootings this year. The last one occurred on February 14 at the Kansas City Chiefs victory parade.

As gunmen fired into the crowd, one was killed and 29 wounded.

There were 656 mass shootings last year, down from 647 in 2022, but up from a record 689 in 2021.

This included 40 mass gun murders across the country, from Texas to Maine. In the first seven weeks of 2024, Americans have already seen seven mass murders, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

Among them was the shooting in Joliet, Illinois, where 23-year-old Romeo Nance killed eight people before committing suicide.

Earlier this month, a man in East Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, shot and killed five of his family members before setting fire to their home. The shooter, identified as Canh Le, 43, also died.

The deadliest shooting of 2023, carried out by an Army reservist in Lewiston, Maine, left 18 dead.

On October 25, Robert Card opened fire at a bowling alley and a bar that had hosted a cornhole tournament before taking his own life in a trailer several miles away.

While this figure fell short of the 21 lives claimed by Uvalde shooter Salvador Ramos the previous year, it surpassed the death toll from what was at the time the worst shooting of the year.

In that shooting, which occurred less than a month into 2023, Huu Can Tran, 72, killed 11 people during a Lunar New Year celebration in Monterey Park, California.

The third worst incident took place at a Texas shopping mall, where alleged neo-Nazi sympathizer Mauricio García shot dead eight people and wounded seven.

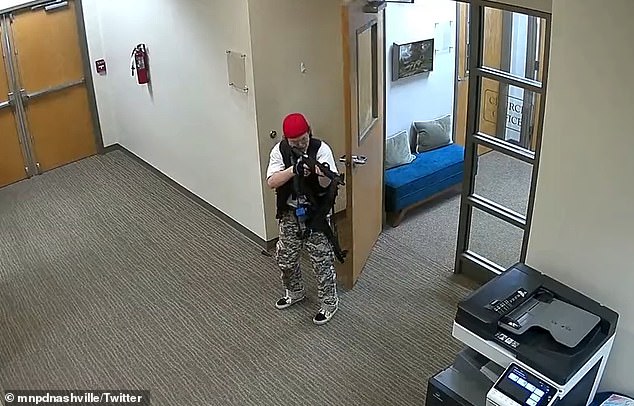

Another took place at a Nashville elementary school in March 2023, in which former student Audrey Hale killed three nine-year-old children and three adults before being shot to death by police.

Also this year, a man in East Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, shot and killed five of his relatives before setting fire to his home and killing himself.

The deadliest shooting of 2023 occurred when Army reservist Robert Card opened fire in a bar and bowling alley, killing 18 people.

Children have figured prominently in the number of deaths from gun violence. According to Gun Violence Archive, 1,385 young people between the ages of 12 and 17 were murdered last year, the highest number in a decade. Another 3,871 were injured.

Young people were also among the victims in Kansas City, as Children’s Mercy Kansas City reported it was treating 11 children between the ages of six and 15, nine of whom suffered gunshot wounds.

The Feb. 14 shooting erupted outside Union Station minutes after the parade concluded.

Police Chief Stacey Graves later told reporters that firearms had been recovered, but declined to comment on how many.

“We have recovered firearms,” he said. ‘I don’t have a number for you or a gauge. “We have recovered firearms.”

The right to bear arms has proven to be a controversial and politically charged issue.

Several US states have passed bans on assault rifles in recent years and have faced pushback from groups who argue the restrictions impede their Second Amendment rights.

A shooting at an outdoor shopping center in Allen, Texas, left nine people dead. Gunman Mauricio García pictured after being shot dead by police

Police cordon off a crime scene in Joliet, Illinois, following a shooting in which Romeo Nance, 23, killed eight people before committing suicide.

Another shooting took place in March 2023 at a Nashville elementary school, in which former student Audrey Hale killed three nine-year-old children and three adults.

The latest state to attempt a ban is Colorado, where two Denver Democrats introduced a measure Tuesday to prohibit the purchase, sale and transfer of a wide range of semi-automatic firearms.

Democratic lawmakers have consistently passed gun control laws in the state since 2013.

This includes provisions for universal background checks, a waiting period on gun purchases, and safe firearm storage.

However, it remains to be seen whether the measure, known as House Bill 1292, will gain enough political support to pass both the House and Senate.

Also on Tuesday, the Illinois State Rifle Association filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court regarding the state’s ban on high-powered rifles.

The law went into effect on January 1 and prohibits the sale and manufacture of weapons such as the AR-15 and AK-47. Those who already owned assault weapons had to register them.

The ban was praised by President Joe Biden in a July 2023 statement released exactly one year after the Highland Park shooting, where a gunman killed seven people during an Independence Day parade in suburban Illinois.

“It is within our power to once again ban assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, require safe gun storage, end gun manufacturers’ liability immunity, and enact universal background checks,” Biden said at that moment.

“I urge other states to follow Illinois’ lead and continue to call on Republican lawmakers in Congress to come to the table on meaningful, common-sense reforms that the American people will support.”

The Kansas City attack claimed the life of Lisa López-Galván, a mother of two and disc jockey for a community radio station.

This year there have been 49 mass shootings, defined as an incident with four victims shot, wounded or killed, not including the shooter.

Maryland’s assault weapons ban also faces pushback from opponents.

Last week, a coalition of gun rights groups asked the Supreme Court to take up his challenge to the state ban before a federal appeals court can rule on the case.

Arguably the most significant development in the gun ownership debate was the Supreme Court’s landmark opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen.

The June 2022 ruling expanded gun rights nationwide and stated that firearms rules must be consistent with the nation’s “historical tradition.”

In December 2023, a federal judge ruled that Massachusetts’ assault weapons ban was consistent with the opinion.

“The relevant history affirms the principle that in 1791, as now, there was a tradition of regulating ‘dangerous and unusual’ weapons, specifically those not reasonably necessary for self-defense,” said U.S. District Judge F. Dennis Saylor. IV. wrote.

The weapons banned in the state “are not suitable for ordinary self-defense purposes and pose substantial dangers far beyond those inherent in the design of ordinary firearms,” Saylor continued.

The law prohibits some semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity magazines. It was passed in 1998 and made permanent after a similar federal statute expired in 2004.