Scientists have proposed a radical plan to stop the melting of a massive Antarctic glacier that would cause catastrophic flooding along the US east coast.

They suggested installing a giant underwater curtain, artificially thickening the glaciers with seawater or cooling the bedrock they slide over to prevent warm waters from reaching the Thwaites Glacier, also known as the ‘Doomsday Glacier’.

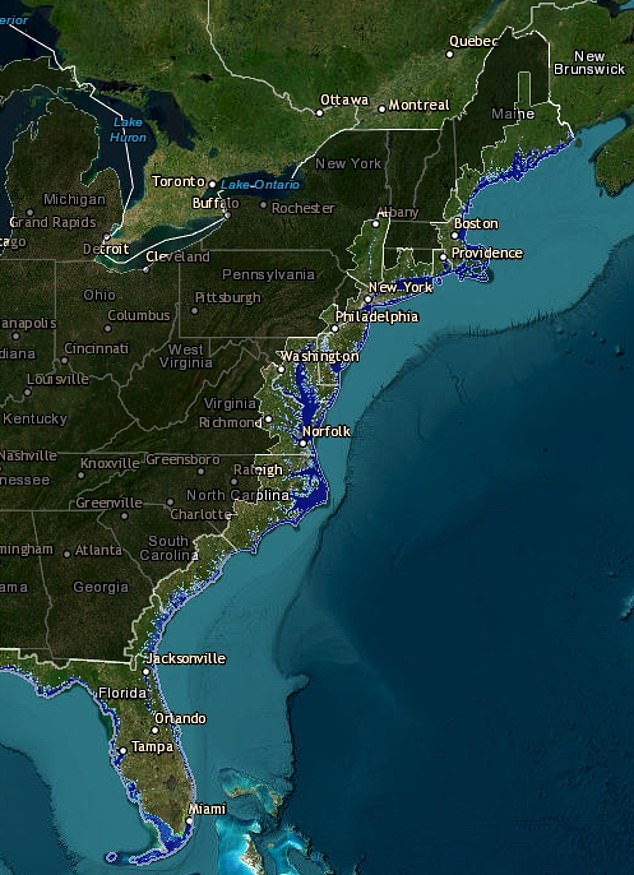

The Thwaites Glacier is melting at an increasing rate due to climate change and would raise global sea levels by 10 feet, flooding coastal cities like New York. Charleston, Atlantic City and Miami.

To prevent this, researchers led by the University of Chicago’s Climate Systems Engineering Initiative published a report calling for a “major initiative” in the coming decades to investigate what interventions, if any, could and should be used.

Douglas MacAyeal, professor of geophysical sciences and co-author of the white paper, said: “Our argument is that we should start funding this research now, so we don’t make panicked decisions in the future, when the water is already lapping at our waters.” our ankles.’

One proposal in the new report would pump seawater to the surface of Doomsday Glacier, where cold air temperatures would cause it to freeze in place and therefore thicken the glacier.

But the idea carries risks and costs, the authors warned.

The salinity of seawater could damage the structural integrity of the ice, and the energy required to pump large volumes of seawater poses unresolved problems.

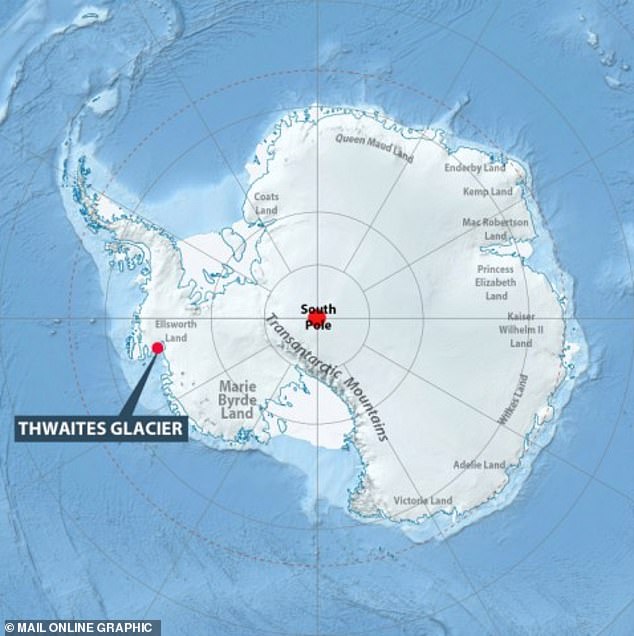

An Antarctic glacier the size of Florida is melting faster than expected. If it collapses, it will cause catastrophic flooding in coastal cities around the world.

If the Doomsday Glacier and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet melt, global sea levels would rise 10 feet (a rise of only six feet is shown in the photo), flooding coastal cities such as New York, Charleston, Atlantic City and Miami.

A UK startup called Real Ice has been working on this solution since 2019. Field tests conducted earlier this year in Canada showed promising results, but implementing it at scale would cost approximately $6 billion per year and would require a huge energy contribution.

This and other interventions analyzed in the report are examples of geoengineering solutions. They intentionally alter the planetary environment to counteract the effects of human-driven climate change.

Some experts have called the ideas “radical,” saying geoengineering “would be difficult or impossible to achieve and would divert attention from the more necessary conversation about reducing carbon emissions.”

Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at the Columbia Climate School, said: “When we talk about glacial geoengineering, we must tell the truth, which is that it is not a solution to climate change; at best, it is a painkiller.”

The Doomsday Glacier spans 74,000 square miles and is losing about 50 billion tons of ice each year, accounting for about four percent of global sea level rise.

It also acts as a natural dam that prevents the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), which covers 760,000 square miles, from collapsing.

This “vigorous melting” is largely due to warm tidal currents pumping beneath the glacier, according to a study published in May in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The white paper, published in July, included results from recent conferences at the University of Chicago and Stanford University on geoengineering.

A team of scientists is urging officials to invest in geoengineering initiatives, such as installing a massive stream to block warm waters.

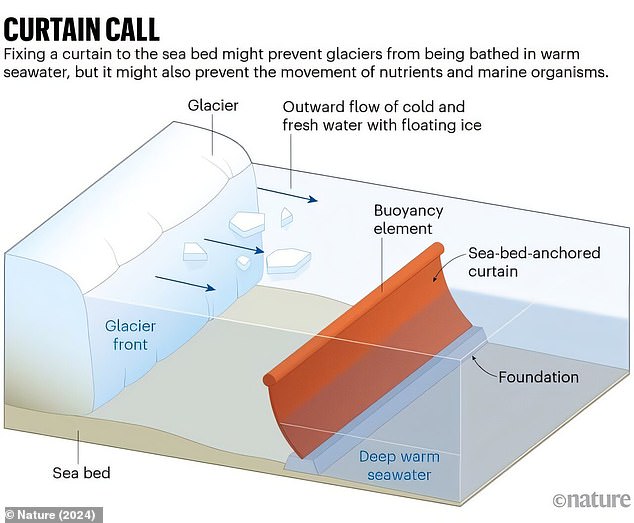

Another proposed intervention would be to prevent warm currents from impacting the glacier by building a giant underwater “curtain” in front of it.

This idea was designed and proposed by glaciologist John Moore of the University of Lapland, co-author of the white paper.

The curtain would be 62 miles long and could cost up to $50 billion to build.

It would anchor to the bottom of the Amundsen Sea, preventing warm underwater currents from hitting the underside of the Thwaites Glacier.

Supported by a floating top edge and anchored at the bottom, the curtain would float on the ocean floor, invisible from the water surface.

Achieving this would require a feat of engineering and construction, not to mention a massive financial investment.

It also carries risks. The white paper notes that blocking heat from cavities under the ice could have effects along the entire coast of the Amundsen Sea.

“For example, if the warm circumpolar deep water circulation shifts westward, it could affect other ice shelves, potentially reducing their stability, while changing the local ecology in uncertain ways,” the report reads.

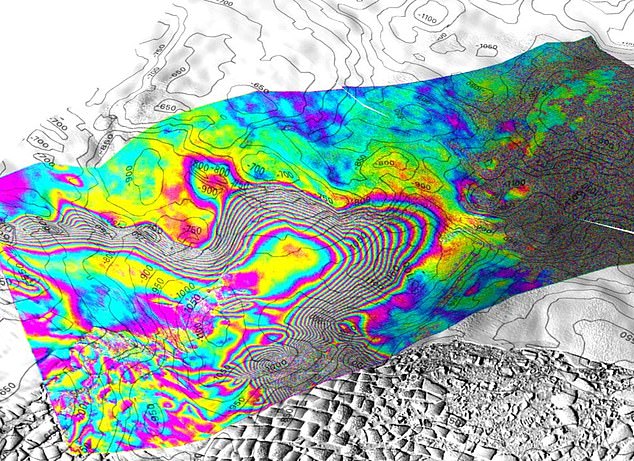

A team of glaciologists used high-resolution satellite images and hydrological data to identify areas where warm tidal currents flow beneath the glacier and cause it to melt faster.

Thwaites Glacier is part of a line of glaciers found along the sea edge of the WAIS.

But Moore is moving forward with his plan. He previously told DailyMail.com that he and his colleagues were working on computer simulations to get the design right, as well as “some small-scale tank testing, basically with fish tanks.”

Other experts believe they can slow glacial melting by cooling the bedrock over which the glaciers slowly slide.

Glaciers are constantly moving towards the sea and, as they do so, their undersurfaces scrape the underlying bedrock, generating friction and therefore heat that causes them to melt from below.

Michael Wolovick, a glaciologist at Princeton University, thinks he could slow this melting by drilling tunnels into the bedrock and pumping cold water through them.

This would combat the heat generated by the movement of the glaciers and thus reduce melting at the bottom of the glacier.

This idea would cost tens of billions of dollars, and the potential risks involved – especially to local ecosystems – require more research.

As researchers sound the alarm about the Doomsday Glacier’s rapidly accelerating rate of melting, more scientists are urging support for geoengineering projects.

“It will take us 15 to 30 years to understand enough to recommend or rule out any of these interventions,” Moore said in a statement.

The white paper came on the heels of May’s PNAS study, which used high-resolution satellite images and hydrological data to identify areas where warm tidal currents flow under the Doomsday Glacier and cause it to melt faster.

This accelerated melting rate could mean that predictions of global sea level rise need to be reevaluated, as catastrophic levels arrive sooner than experts previously thought, the researchers concluded.

The loss of Doomsday Glacier would also lead to the collapse of the WAIS, the continental ice sheet that covers West Antarctica.

The WAIS is essentially a bowl of ice three times the size of Texas located in a basin below sea level in West Antarctica.

Thwaites Glacier is part of a line of glaciers found along the sea edge of the WAIS.

These glaciers are the only thing preventing the ocean from filling the WAIS basin and melting or dislodging its ice.

If both Thwaites and WAIS were to collapse, it would cause extreme, irreversible sea level rise that would endanger millions of people and accelerate the melting of other glaciers around the world.

Climate scientists classify this potential disaster as a “tipping point,” or the crossing of a critical threshold that leads to major, unstoppable changes in the climate system.

‘We expected it would take a hundred or five hundred years to lose that ice. A big concern right now is whether it happens much faster than that,” said Christine Dow, co-author of the study and associate professor of glaciology at the University of Waterloo. American scientist.