If Caravaggio had stopped at artichokes.

The Italian artist, one of the greatest of the 17th century, had a prodigious talent and a temperament to match.

Hitting a waiter in the face with a plate of vegetables was the mildest act in a criminal career that included bar fights, drunken riots, alleged sexual assaults and a prison escape.

So far, so bad. Then in Rome in 1609, things got even uglier.

When fighting, supposedly over a tennis match, he drew his sword and murdered his opponent. With a death sentence hanging over his head, he fled south to Naples. Ruled by Spain, this prosperous city was outside the jurisdiction of Rome. So here, at least until his next act of stupendous madness, he was safe. It was here that he made some of his most famous paintings.

Masterpiece: Deirdre Fernand travels to Naples (pictured) to explore the legacy of Italian artist Caravaggio, who fled to the city in the 17th century.

So it is to Naples that the National Gallery is looking for its latest exhibition, The Last Caravaggio, which opens in London next Thursday. It will focus on his final work, The Martyrdom of Saint Úrsula.

It has been inserted into the image. It would be her last self-portrait. Nine weeks later he died of fever at age 38.

What better place to go in search of Caravaggio (born Michelangelo Meravisi in 1571) than Naples, Italy’s third largest city after Rome and Milan.

The city, gateway to the Amalfi Coast and Pompeii, rarely appears as a destination in itself. More is the pity.

“Best view I’ve ever had,” my husband shouted from the balcony of our hotel, the Paradiso. Beyond us stretched the silver-blue bay of Naples and Mount Vesuvius shining in the sun.

When Caravaggio arrived in 1610, he was already a star of the Baroque, praised as a successor to Leonardo and Michelangelo. Only three of the approximately 80 paintings attributed to him remain in the city.

Caravaggio’s Seven Acts of Mercy exhibited in the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia

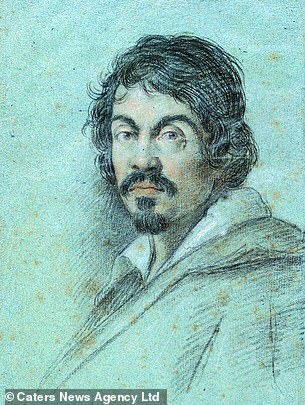

Above, a portrait of Caravaggio

This historic settlement, first colonized by the Greeks in 600 BC. C., has more than 450 churches and a tangle of medieval streets.

Feeling lost, panic took hold. Then we saw the artist himself. A miracle?

No, just a Caravaggio double, in 17th century attire, doing business in front of the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia.

Here we find ourselves in front of the artist’s imposing altarpiece, The Seven Acts of Mercy.

It represents a series of good works, such as feeding the hungry and caring for the sick.

His genius was to combine these facts into a large composition and place all the actions on a normal street in Naples.

The city has always been a place of pilgrimage for more than just art lovers. Some ask for miracles from San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples. Others come to pay tribute to Maradona, the legendary Argentine soccer star who brought glory to Napoli in the 1980s. The player, who died four years ago, appears in a giant mural in the Spanish Quarter.

And then there are the millions who come for the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Visiting the former on a bright afternoon with guide Luca, we walked along ancient paths, trying to imagine the lives of the citizens who met their deaths when Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD 79.

Deirdre reveals Naples has around 450 churches and a ‘tangle of medieval streets’

Naples is the gateway to the Amalfi Coast and Pompeii above, with Mount Vesuvius in the background.

Luca was not impressed with our knowledge of the Roman emperors and made us promise to go to the city’s National Archaeological Museum to learn more.

We bought a children’s guide to the ancient world (plus a slice of Neapolitan pizza), sat in the cafe and got steamy.

Augustus, Nero, Titus… how much there was to know.

We promised to return to this crowded but exciting city. Come for Caravaggio, stay for Caesar.