Table of Contents

Fashion conscious: Nowadays Next sells not only its own brand, but many others

The story of Next, the £12.5bn retail giant, began 160 years ago in Leeds. The company, then known as Hepworth, was the first High Street chain to offer bespoke and ready-to-wear tailoring.

Next’s transformation into a 21st century clothing and home goods powerhouse is an example of how to survive and thrive amid radical changes in an industry. The company, which is ranked number one in the UK clothing market, is prominent in the shopping center and also online.

Today, Next sells not only its own brand, but many others, including Gap, Laura Ashley, New Balance, Victoria’s Secret and The White Company. Maintaining its tradition in tailoring, the retailer also owns 72 percent of Reiss, the luxury chain famous for its elegant suits.

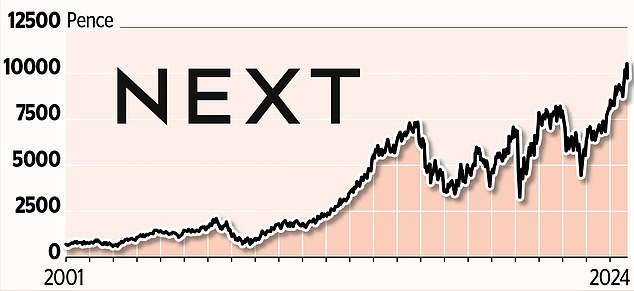

No wonder Next shares, which have soared 33 per cent this year, are seen as one of the stocks to own if you want to back big British companies that are also set to become global stars.

Last month the company reported a 14 per cent rise in half-year sales to £2.86bn. Interactive Investor’s Richard Hunter praised the figures as “next-level figures.” He maintains that Next, under its cerebral chief executive Simon Wolfson, has “an unparalleled understanding of the market in which it operates and its ability to capitalize on new opportunities.”

Some of these opportunities will arise here at home. In recent days, Next has acquired a 16 per cent stake in homewares brand Rockett St George.

But there may be other opportunities abroad, given the growing international demand for Next fashion. A spokesperson for the retailer says that thanks to the influence of Netflix series, the tastes of various countries are converging.

Next also forecast it would generate £1bn in profits for the full year, even in a tough economic climate. This prediction was not seen as an exaggeration, as Next tends to underpromise and overdeliver.

Rathbones Asset Management’s Will McIntosh-Whyte is optimistic about the outlook. He says: “The company is well positioned to take advantage of the British consumer recovery, provided the new government does not destroy consumer confidence with its doom and gloom talk.”

Ben Preston of the Orbis Global Equity fund is also optimistic about Next’s prospects. He says: “Strong companies can often take advantage of tough times, and that’s exactly what Next has been able to do.”

This ability to adapt to circumstances began to become evident back in 1987, when Hepworth changed her name to Next. The move was a recognition that its future lay not in old-fashioned formal wear, but in the Next fashion stores created in 1982.

These stores, which cater to younger women looking for glamorous outfits, were the brainchild of George Davis, a major retail personality of the 1980s.

Davis, who launched Per Una at Marks and Spencer and George at Asda, was chief executive of Next between 1984 and 1988. Although this was a turbulent period, the innovative retailer ushered in a new era.

This pattern of disruption resumed under Wolfson, 56, who took over in 2001, having spent a period working in Next’s shop after graduating with a law degree from Cambridge. It has ably weathered the subsequent attrition of the retail sector that has claimed victims such as Debenhams.

Its rivals may have closed their stores, but Next has 460 stores and will open more. It also has a sophisticated online offering based on the infrastructure of its mail-order arm Next Directory.

Next’s total platform, established in 2023, provides distribution, warehousing, website and other services to other retailers for a fee.

Such is the investment in logistics, IT systems and software to service Total Platform and the online shopping revolution that Next now employs more people in technology than in its product divisions. As Wolfson says: “History has received a push, and having moved forward, it seems unlikely to go backwards.”

Fidelity UK Select Fund portfolio manager Aruna Karunathilake, a long-time investor in Next, underlines the extent of the shift to online. He says: “Most people think of Next as a brick-and-mortar retailer given its presence on our high streets, but in reality in-store retail now accounts for less than 10 per cent of its profits.”

This radical change in the nature of the business explains the general approval that Next enjoys and the respect for its stance even on controversial issues.

Last month, the company said it could close stores if it lost an appeal against a long-standing equal pay claim. But this did not stop the rise of the share price. The assumption seemed to be that Next would follow its usual policy of closing less profitable stores, rather than penalizing workers.

AJ Bell’s Russ Mold describes the company’s management as “a showcase of how to run a public company.” He highlights the “detailed guidance” Next provides. Its report and accounts outline the reasoning behind its strategy, mentioning mistakes that have been made, for example, in acquisitions, but also how others have been avoided.

Next regularly steps in to snap up struggling names like FatFace and Made.com, the furniture company. However, Wolfson maintains that this does not mean Next is a conglomerate, suggesting it is more like a group of venture capitalists.

In the “Overview” section of the report and accounts, Wolfson sets out the tasks ahead. These pages give a clue to his thinking: his public pronouncements are relatively rare… and to the point.

It is this candor that investors appreciate about Wolfson, who, as Baron Wolfson of Aspley Guise, sits in the House of Lords. As the son of a former Next chairman, Lord Wolfson of Sunningdale, he could be seen as a beneficiary of nepotism, but it is difficult to find anyone who holds this view.

Their experience is respected and so is their discreet lifestyle. In his free time, Wolfson, a father of three, enjoys gardening. It also sponsors the £250,000 Wolfson Economics Prize.

His wife, Eleanor Shawcross, was an adviser to Rishi Sunak as Prime Minister and George Osborne during his time as Chancellor. Wolfson is unlikely to leave anytime soon, although he is the longest-serving chief executive in the FTSE 100. He loves his job and investors hope he stays that way.

A long-term wait for future growth

If you’re thinking about adding Next to your portfolio, don’t look for a quick death. This is a long-term bet on economic recovery in the UK (and elsewhere).

Next shares have risen 50 per cent in the last five years to 9,742p. As a result of this increase, 13 of the analyst teams at the brokerage firms that follow the stock consider it a ‘hold’ and four ‘buy’.

Rathbones’ McIntosh-Whyte is among those who argue the valuation may be overstated, even if only in the short term.

Others are more confident. Fidelity’s Karunathilake argues that Next is undervalued by the market due to its good return on equity and cash flow.

Shares are valued at 15 times earnings, in line with other retailers. But Karunathilake says this underestimates Next’s online capabilities. This will be the driver of its expansion in Great Britain and beyond.

DIY INVESTMENT PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-to-use portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free Fund Trading and Investment Ideas

interactive inverter

interactive inverter

Fixed fee investing from £4.99 per month

sax

sax

Get £200 back in trading fees

Trade 212

Trade 212

Free trading and no account commission

Affiliate links: If you purchase a This is Money product you may earn a commission. These offers are chosen by our editorial team as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.