In 2012, Geri Taylor was a senior executive at a large long-term care facility in NY when he began to experience signs of cognitive decline.

On one occasion, the 69-year-old woman lost her train of thought during a work meeting. On another occasion, she got off at the wrong subway stop and couldn’t remember where her house was.

Then, one morning that same year, he was surprised to see his reflection in the mirror. She couldn’t recognize herself.

A visit to the neurologist in November of that year confirmed the worst: he was in the early stages of cognitive decline, a precursor to Alzheimer’s.

Studies suggest that around eight in 10 patients with so-called mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

And Geri felt like that second shoe would drop before long.

While the disease had not yet reached full force at that time, he felt as if he were in a kind of purgatory, anticipating its devastation.

![I took the now-defunct Alzheimer's medication for seven years and it 'paused' my disease - without it there's no hope 6 Geri [left] and Jim Taylor [right] spoke to DailyMail.com about Geri's journey to Alzheimer's and the benefit a now-discontinued medication had for her](https://whatsnew2day.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/I-took-the-now-defunct-Alzheimers-medication-for-seven-years-and.jpeg)

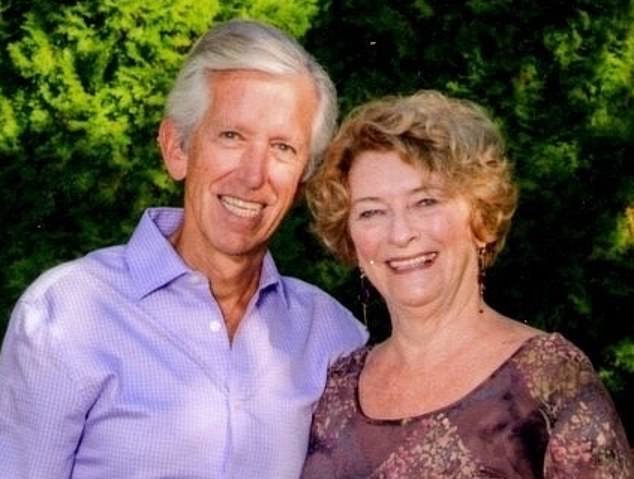

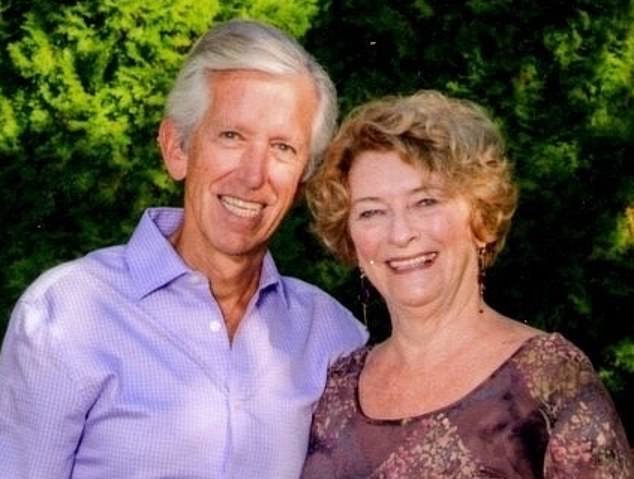

Geri [left] and Jim Taylor [right] spoke to DailyMail.com about Geri’s journey to Alzheimer’s and the benefit a now-discontinued medication had for her

The couple took advantage of Geri’s near-normal cognition during the early years of having Alzheimer’s, traveling and speaking at conferences about caring for the disease.

Three years later, while flipping through the newspapers one morning, Geri’s husband Jim came across an advertisement about an early-stage trial of a promising new drug for cognitive decline in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

The drug was called aducanumab. Its approval under the Food and Drug Administration’s accelerated approval pathway was controversial, because the scientific evidence that it worked was weak and possible side effects included inflammation and brain bleeding.

The couple called Yale-New Haven Hospital about two hours from their New York City apartment where the trial was taking place. The test had few places left and Geri took one of them.

The injectable antibody, a “fighter” protein, was designed to eliminate amyloid plaque in the brain. This sticky buildup is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, which doctors look for in brain scans.

Geri’s PET scans revealed significant amyloid plaque buildup. This, along with her increasingly deteriorating memory, meant that she met the requirements to participate in the study.

DNA testing offered clues as to why Geri may have developed the disease relatively young.

Both his mother and father tested positive for the APOE4 gene variant, which increases the risk of Alzheimer’s eight to 12 times. This means that her son is also predisposed to Alzheimer’s disease.

During the seven-year trial, Geri received a high dose of the real drug, not the placebo. And it wasn’t long before she felt an improvement in her ability to improvise sentences.

Jim told DailyMail.com: ‘OrOur lives during those first five or six years. [on the trial] He was remarkably calm.

Geri seemed to benefit from the medication during the trial. She was able to form sentences and retrieve the correct words with relative ease, giving the couple a few extra years of lucidity.

Together they traveled across the country to give talks at churches and conferences about living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Geri participated in support groups and memory workshops organized by the CaringKind organization that connects patients and families with their caregivers.

‘Geri always did 50 percent of the presentation. We went from one side to the other, a kind of ping pong. And she was able to pack and keep track of our itinerary and she really needed very little, if any, help from me for many years.

“We were excited about that and felt like she was benefiting from the medication infusions.”

During that time, Geri became a social butterfly, eager to meet new people and spend time with those closest to her, making the most of her years of clarity.

But then the trial stopped abruptly.

In March 2019, Biogen and pharmaceutical partner Eisai announced that they would end the trial in which Geri was enrolled.

This was based on an interim analysis that led the company to scrap the drug and tell more than 3,000 Alzheimer’s patients that they would no longer receive the infusions.

Geri went a full year without the medication she and her husband believed had helped her cognitive decline.

Jim said: ‘And I noticed during that year, for the first time, that she began to have difficulty with words and the ability to keep a conversation flowing. And she realized that too. And that to me was reinforcement that the drug had been helping.”

Aducanumab is a monoclonal antibody made from living cells that bind to a sticky protein called amyloid beta. Amyloid beta proteins are found naturally in the brain.

A brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease overproduces the precursor proteins that generate beta amyloid, which appear in abnormal forms that clump together in insoluble clumps.

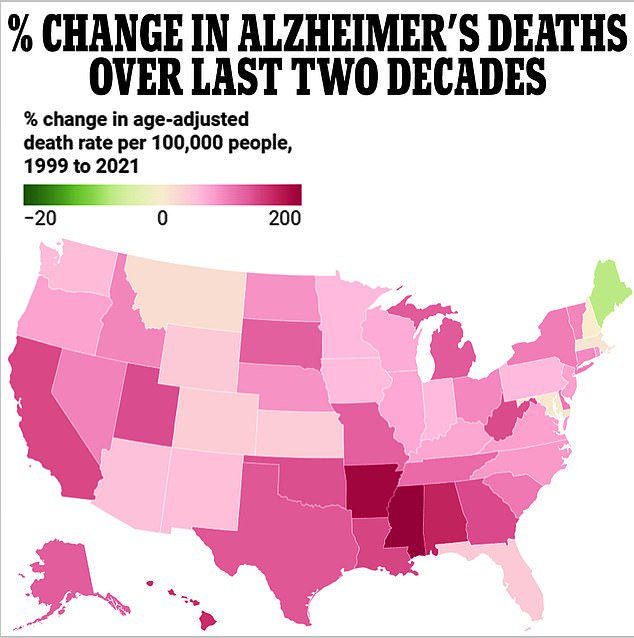

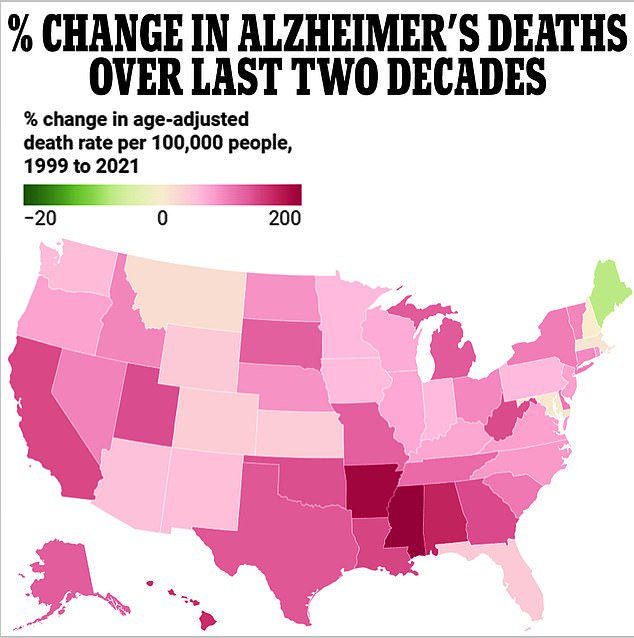

All but one state has seen an increase in Alzheimer’s deaths over the two decades through 2021, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows.

These clumps disrupt normal neuronal function and cell signaling pathways, eventually killing those cells.

Amyloid is a marker of Alzheimer’s and the target of several other drugs in the pipeline besides aducanumab. But the scientific evidence that reducing amyloid can alleviate memory and thinking problems is weak.

Clinical trials of other amyloid-targeting drugs over the past two decades have failed in slow cognitive decline. This has led to some disagreement in the scientific community about whether drugs should focus excessively on lowering amyloid.

The trial resumed in 2020 and Geri was able to rejoin, but she had lost a valuable year of treatment in which her cognitive decline could have been delayed.

The drug has been plagued with controversy since its inception.

The eventual June 2021 approval was the source of years of controversy and investigation into possible clandestine communications between FDA staff and the drug’s manufacturer.

When it passed narrowly, acceptance was low. Biogen put a sticker price of $56,000 a year.

Since the vast majority of Alzheimer’s sufferers are 65 or older and on fixed incomes, compounded by the fact that Medicare, which provides health coverage to seniors, limited their coverage of the drug, not many people were able to get it.

Earlier this year, Biogen decided to discontinue the drug it had called Aduhelm, which the company said was “not related to any safety or effectiveness concerns.”

Had the trial not been shortened, Geri may have continued to benefit from the infusions.

But when it resumed, Geri’s illness had progressed to a point where she was no longer likely to see any benefit.

Jim said: ‘[New medications in development] They are trying to detect people who are likely to develop the disease before symptoms begin.

“But at this stage and in the illness in Geri’s journey, I would say that there are no innovative medications that will slow the cognitive decline in her. The drugs at this stage are mostly symptomatic drugs, which try to control behaviors like laying down. sun.

Geri is now in a memory care unit full time. Last summer, she began having significant symptoms of sundowning, or confusion in the late afternoon and evening, which can be extremely distressing for patients.

But even without her by his side all the time, Jim continued his work advocating for Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers. They founded Voices of Alzheimer’s on behalf of the approximately six million Americans living with the disease.

One of the organization’s first goals was to establish a patient “Bill of Rights” requiring ethical treatment by providers who understand the disease.

Jim recounted a harrowing experience that indicated to him that such a bill was necessary: ’One time, Geri was hospitalized and I couldn’t walk her to her room. And I got to her room 30 minutes later, and three attendants were trying to force her into a hospital gown and she was hysterical.

“Then I found out that the assistants are not even trained, and the hospitals are not trained to differentiate between patients with dementia.”

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, although there are treatments that can slow the progression of the disease. Aduhelm was the first Alzheimer’s treatment to come to market in about 18 years, earning the endorsement of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Research into new treatments is ongoing and Biogen said it will repurpose resources toward the development of an alternative treatment. But funding for Alzheimer’s research is not as strong as advocates believe it should be.

Today, funding for Alzheimer’s and dementia research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) exceeds $3.7 billion annually. For comparison, the National Cancer Institute’s budget in 2023 was $7.3 billion.