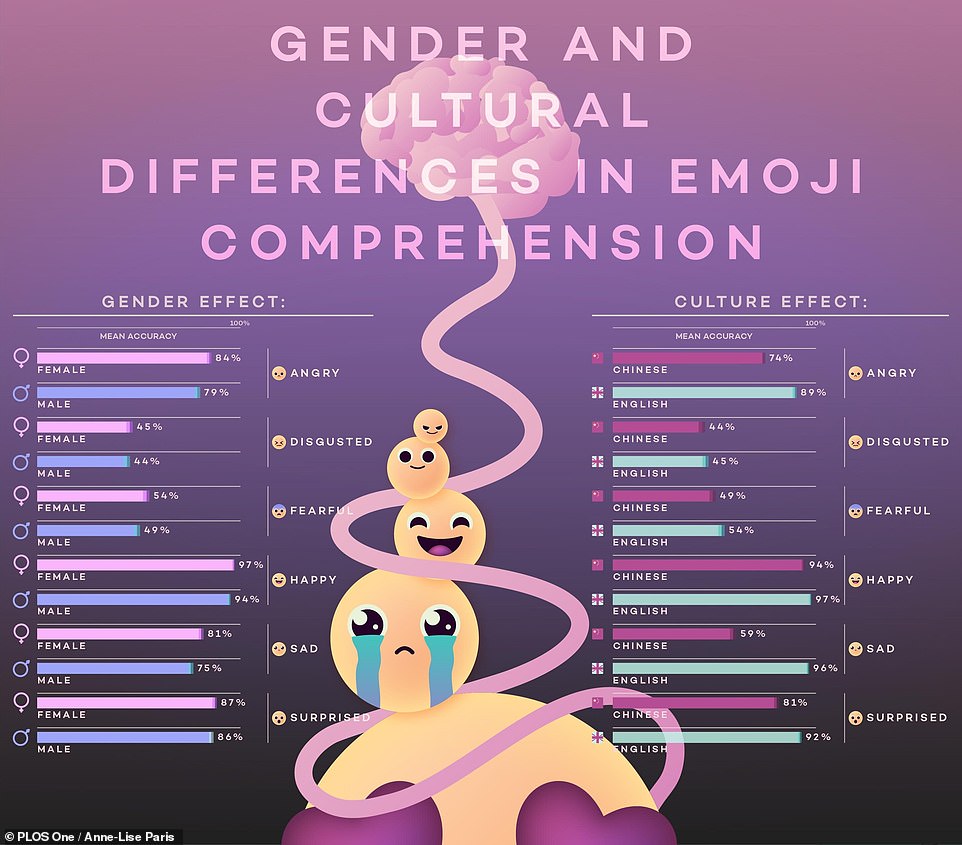

- Women were better at identifying emoji emotions, and researchers theorized that childcare skills gave them an advantage.

- READ MORE: Second guess each text? Scientists discover that people use happy emojis to hide negative emotions

Advertisement

Men struggle to understand the meaning of emoji faces because they are less sensitive than women, according to a study.

Researchers asked 500 men and women in the United Kingdom and China to identify emotions represented by a series of small yellow icons popular in text messages and social media posts.

They also found that Brits had a harder time recognizing the “disgust” face, possibly because the infamously reserved Brits are less likely to express that emotion, keeping their displeasure closer to the vest.

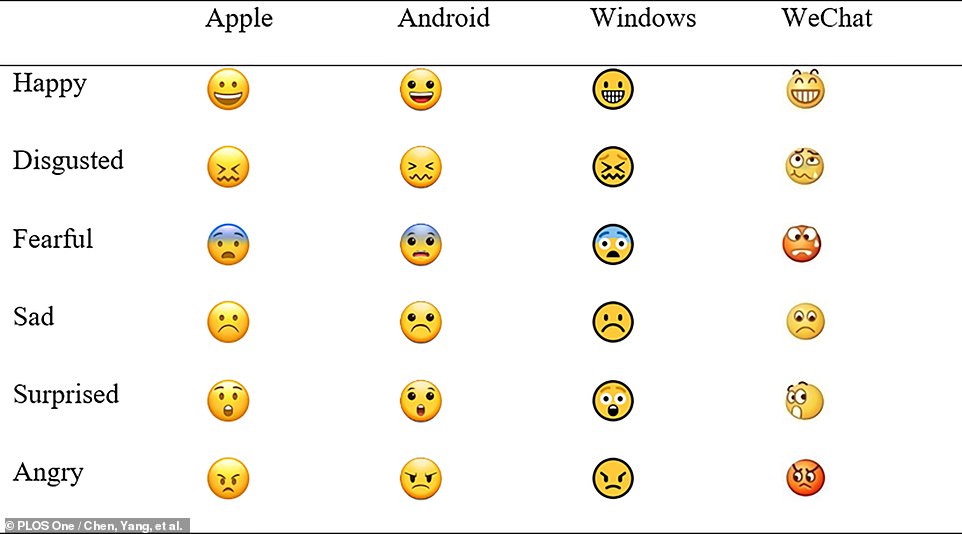

Study participants looked at emojis representing happiness, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise and anger.

Researchers asked 500 men and women in the United Kingdom and China to identify emotions represented in a series of emojis, those little yellow icons popular in text messages. Women surpassed men in being more insightful when it came to reading the meaning of the icons.

Study participants observed emojis representing happiness, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise, and anger, across multiple technological operating systems that varied in emoji design (above).

Women fared better across the board. The researchers said this may be because women are better able to recognize the emotions of human babies.

Yihua Chen, from the University of Nottingham, said: “Women demonstrate greater accuracy in emotion recognition than men. One possible explanation is the ‘primary caregiver hypothesis.’

“Quickly and accurately identifying infant emotions, especially facial expressions, is a very important part of infant care, as infant mortality has generally been high throughout human evolution.”

Overall, Westerners did better than Chinese in recognizing emoji emotions, but struggled with the “disgust” face, which has low features with a trembling mouth, a frown and closed eyes. The researchers said this may be due to “specific emotional experiences in different cultures.”

They also noted that in China, the “smile” face was often used to represent emotions other than happiness. The study was published in the scientific journal. Plus one.

Britain is one of the most emoji-hungry nations in the world, and half of us send at least one every day. They are also popular across all age groups, with little variation between generations.

The researchers found that English posts on X, formerly Twitter, were also riddled with emojis, more so than on China’s Weibo social media platform.

Emojis are a standard feature on smartphones and computers. Cartoonish faces expressing various emotions date back to the 1990s and have since become a cultural element.

In fact, in 2015, Oxford Dictionaries made the “crying with laughter” emoji their “word of the year.” Casper Grathwohl, vice-president of Oxford University Press, said at the time: “Traditional alphabetic scripts have been struggling to meet the rapid, visually focused demands of 21st-century communication.”

“It’s not surprising that a pictographic script like the emoji has stepped in to fill those gaps: it’s flexible, immediate, and wonderfully infusing tone.”

“As a result,” Grathwohl concluded, “emoji are becoming an increasingly rich form of communication, transcending linguistic boundaries.”