Women who go to the emergency room with pain are less likely to receive the medications they need to treat it compared to men, new research shows.

An analysis of discharge notes from more than 21,000 patients in Missouri and Israel showed that female patients were less likely to be prescribed painkillers and more likely to have their symptoms ignored.

Co-author Dr Alex Gileles-Hillel, a physician at the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, said: “Women are seen as exaggerated or hysterical and men are seen as more stoic when complaining of pain.”

It’s the latest evidence of sex bias in medicine: Women are also less likely to be treated for a heart attack than men.

Doctors test gender bias in medicine by presenting male and female nurses with identical fictional vignettes about a male patient and a female patient with severe back pain.

When asked to assign a pain management score to male and female patients with exactly the same complaint and health history, nurses perceived the female patients’ pain as less intense and less deserving of treatment.

Pain is subjective and doctors and nurses rely on patients to rate it on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being unbearable.

Medical professionals decide whether or not to give painkillers and how strong they should be based on what patients tell them.

The latest research published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences They reported that women, even when they rated their pain high on the scale, were almost 20 percent less likely to receive pain medication than men, even when their self-reported pain ratings were the same.

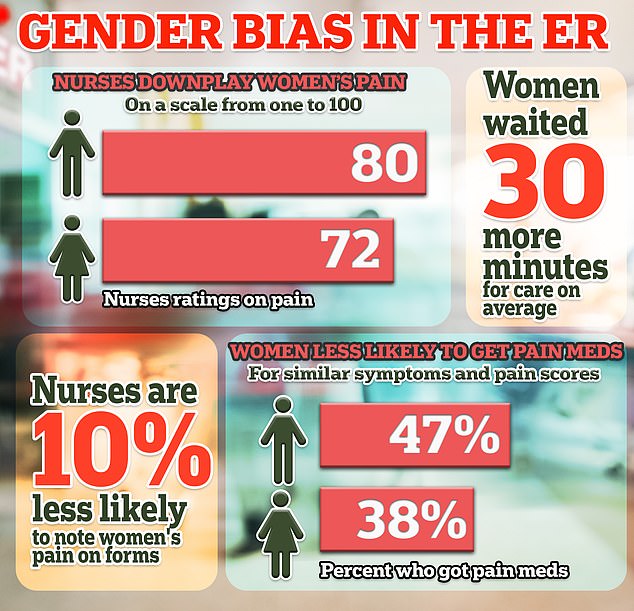

Using notes describing patients’ treatment written when they left the hospital, doctors found that 38 percent received some type of pain-relieving medication, compared with 47 percent of male patients with similar symptoms.

Women tended to rate their pain slightly lower than men: 6.64 versus 6.81.

But the researchers took this into account and found an equally disparate pattern across all pain ratings.

Further analysis revealed that nurses were 10 percent less likely to record women’s pain scores, increasing the likelihood that they would not receive the care they needed.

Women tend not to be taken seriously when they complain of health problems such as breast pain, increasing the chances that they will suffer or die from a condition that could have been prevented.

And women tended to spend an average of 30 extra minutes waiting for a nurse or doctor to see them in the emergency department, compared with men, who spent less time in the waiting room.

To further test their hypothesis—that there is a gender bias in emergency rooms—the researchers gave brief written descriptions of patients to 109 nurses at a Missouri hospital to judge the intensity of the patient’s pain.

The scenarios written for a male patient and a female patient were exactly the same. The only difference was the gender of the fictional patient: ‘Mrs. (Mr.) Jones presents to the Emergency Department.

‘This is a 44-year-old man (woman), previously healthy. He presents with sharp, stabbing back pain that began gradually the previous day.

‘She (he) rates her pain a 9 out of 10 and says it interferes with her functioning. Mrs. (Mr.) Jones has reportedly not tried anything yet to relieve the pain, is otherwise healthy, and is currently not taking any other medications.’

Each nurse was then asked to rate her perception of this pain on a scale of one to 100 (maximum pain).

When the nurses were presented with the vignette describing a man, they tended to rate their pain closer to 90, with an average of 80.

But when a description from a woman was presented, the average pain rating was 72. The disparity persisted regardless of whether the nurse rater was male or female.

The researchers called this gap a sign that women’s pain is often “overlooked,” which has “worrying social and medical implications.”

Women who seek a doctor’s help for pain relief simply tend to be taken less seriously than men, a product of centuries of portraying women as more emotional and dramatic than men and more likely to exaggerate their pain.

A 2009 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health reported that women were double the odds like men who were given a mental health diagnosis when they went to the doctor with symptoms of heart disease.

Swedish researchers saying in 2018: ‘Women in pain may be perceived as hysterical, emotional, whiny, unwilling to get better, pretending to be sick and inventing the pain, as if it were all in their head.

‘Other studies have shown that women with chronic pain are attributed to psychological rather than somatic causes for their pain.’

The disparity between the care women receive and that received by men is most clearly evident in cases of women who present to the emergency department with symptoms of a heart attack.

A 2022 study found that men were around 22 percent were more likely to be seen by a doctor immediately when they experienced chest pain than women.

Women had to wait 29 percent longer than men to see a doctor — about 11 extra minutes. And when a person is in the midst of a heart attack, those 11 minutes can mean the difference between survival and death.