<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

He has been one of the most prominent faces on the Awards Season circuit.

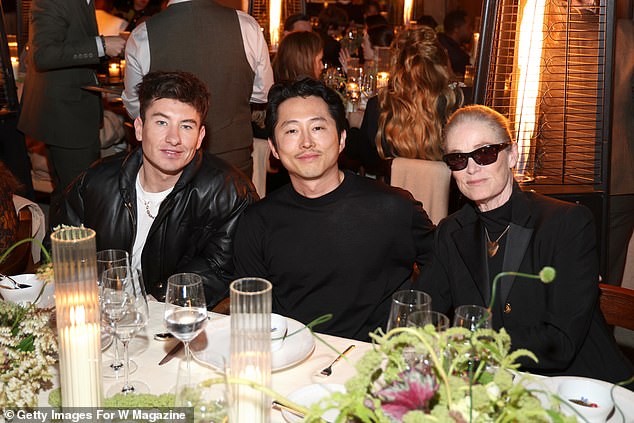

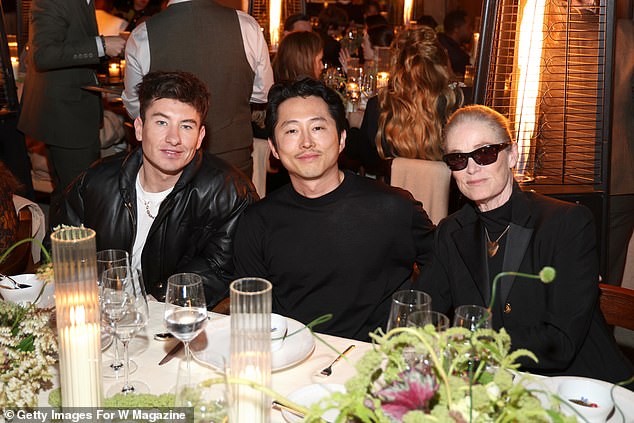

And Barry Keoghan mixed with Hollywood’s crème de la crème again on Thursday night when he attended the W Magazine and Louis Vuitton Academy Awards dinner in Los Angeles, ahead of Sunday’s Oscars.

The Irish star, 31, looked stylish in a white crew-neck t-shirt teamed with a leather bomber jacket as he lived with a host of stars.

As he continues to enjoy the huge success of Saltburn, Barry seemed delighted to be among the stars, including Lana Del Rey and Zendaya.

In a celebration of their joint success, she was putting on a playful display with her Saltburn co-star Archie Madekwe, 29, who played Farleigh Start in the film Emerald Fennell alongside Barry’s character Oliver Quick.

Barry Keoghan mixed with Hollywood’s crème de la crème again on Thursday night when he attended the W Magazine and Louis Vuitton Academy Awards dinner in Los Angeles ahead of Sunday’s Oscars.

The Irish star, 31, looked stylish in a white crew-neck T-shirt paired with a leather bomber jacket while hanging out with a host of stars, including Zendaya.

In a celebration of their joint success, she was putting on a playful display with her Saltburn co-star Archie Madekwe, 29, who played Farleigh Start in the film Emerald Fennell alongside Barry’s character Oliver Quick.

Archie and Barry starred in Saltburn

Barry’s night on the town comes after he was unveiled as the new face of Burberry following his recent collaborations with the iconic heritage brand.

The fashion house announced on Thursday that Irish actor Barry has been named the brand’s new ambassador.

Barry follows in the footsteps of famous ambassadors of the past including; Cara Delevingne, Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, Emma Watson and Rachel Weisz.

Speaking about his excitement following the reveal, Barry said: “I have been a Burberry fan for many years.

‘It is such an iconic heritage brand with innovation at its heart and a commitment to supporting arts and culture. “I am very excited to be a part of this next chapter.”

Speaking about the news, the brand’s creative director, Daniel, said: “I’ve known Barry for over 5 years and have watched him become one of the most talented actors of his generation.”

‘Their pure and unique talent is incredibly inspiring and perfectly reflects the spirit of our brand. “I am proud to welcome him to the Burberry family.”

The 96th Academy Awards honor the best films of 2023, with a dazzling ceremony held at the Dolby Theater in Hollywood.

He seemed delighted to be with Jaden Smith in one of his snapshots.

He posed happily with journalist Lynn Hirschberg.

Last year’s most anticipated films, Barbie and Oppenheimer, lead the nominations.

Oppenheimer has earned 13 nominations, including best picture and best actor for Cillian Murphy, who is the favorite to win the top category after winning a BAFTA, a Golden Globe and a SAG Award for his role as physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The impressive total, which also includes best actor and supporting actress for Robert Downey Jr. and Emily Blunt, as well as best director for Christopher Nolan, is just one nomination away from the all-time record set by Titanic in 1998.

For the award for best leading actor, Bradley Cooper and Cillian Murphy will compete for the award. Colman Domingo, Paul Giamatti and Jeffrey Wright also received nominations.

Leonardo DiCaprio was not recognized for his performance in Killers Of The Flower Moon.

The awards will take place on March 10 at 7 pm ET/4 pm PT live on ABC, and will be hosted for the fourth time by Jimmy Kimmel.

He wowed with his modern leather jacket.

Barry’s night on the town comes after he was unveiled as the new face of Burberry following his recent collaborations with the iconic heritage brand.

He sat at the table with Steven Yeun and Lisa Love.