There was something missing from Sunday night’s SuperBowl that not even an appearance by Taylor Swift cheering on her soccer star boyfriend could make up for.

Joe Biden skipped the traditional pre-game presidential interview, a 15-year White House tradition. Given that it is a light-hearted affair, with no probing questions and reaching some 60 million viewers that night, the decision of any presidential candidate to let it slide with a general election just around the corner seems almost inconceivable.

The Biden team’s explanation was not convincing. Sports fans “don’t want anything to do with a politician, so I think he made the right decision at this point,” explained campaign co-chairman Mitch Landrieu.

Americans would actually love to hear from Biden, but they have precious few opportunities beyond rare, tightly controlled press conferences and meetings with international politicians like Rishi Sunak, where the Leader of the Free World works off letters of reference. When it goes off script, it is invariably disastrous.

US President Joe Biden and First Lady Jill Biden walk on the South Lawn of the White House yesterday.

Former first lady Michelle Obama speaks about her book Becoming at the Barclays Center, New York, in 2018.

Republicans, of course, have been issuing warnings about an increasingly doubtful Biden for years. Donald Trump insisted before the 2020 election that his gaffe-prone political rival had fallen into senility.

At the time, Democrats dismissed such jibes as tasteless scaremongering. But now the left is also expressing its fears.

“Biden is not just in a bubble: he is wrapped in bubble wrap,” one of the most famous political commentators in the United States, Maureen Dowd, observed on Sunday.

“Coddling and locking up Uncle Joe… avoiding the town halls and the Super Bowl interview, they’re just not going to work,” he said. “Keeping quiet about his health” is no longer possible, he added, and the sooner President Biden’s team stops denying it, the better off Democrats will be.

Americans are worried about the president’s “twilight attitude,” Dowd warned. “It’s the elephant in the room, except elephants never forget.”

That concern has spiked after a series of distracted “high-profile moments” by the 81-year-old president in recent days, including his penchant for confusing the names of world leaders.

Joe Biden, pictured with the Kansas Chiefs stars in 2023, skipped the traditional pre-SuperBowl presidential interview last night, a 15-year White House tradition.

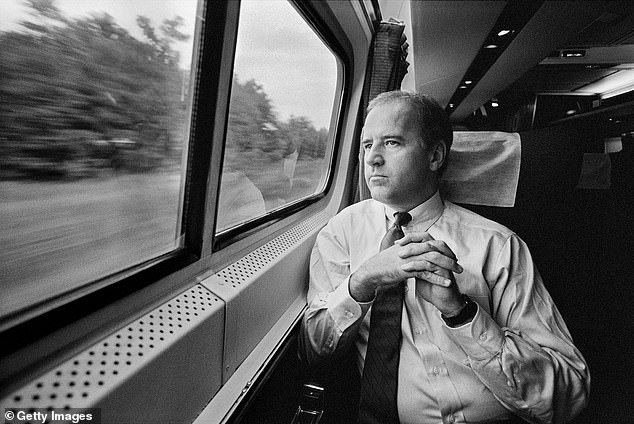

Joe Biden, pictured in his time as a US senator, has been accused by researchers of suffering from memory lapses

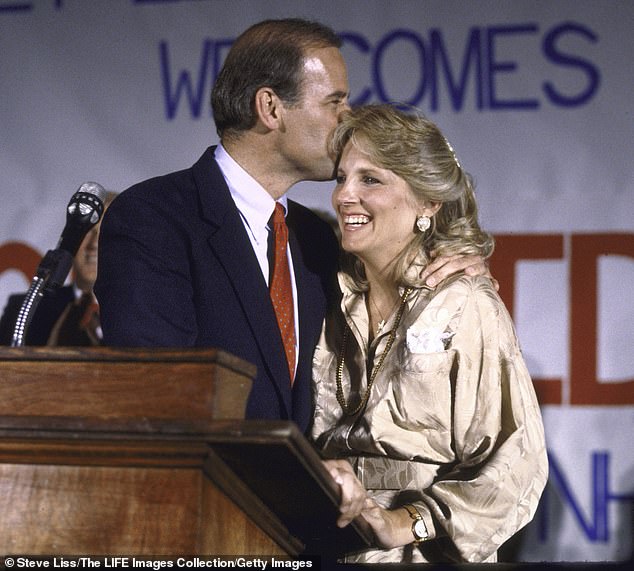

Joe Biden with his family after declaring that he would run for president in 1987

Dowd is not a Trump cheerleader, she is a columnist for the left-wing New York Times, until now a staunch supporter of Biden.

In recent days, its pages have been filled with articles full of pessimism about the president’s age and his electoral prospects. The newspaper has made clear its opinion that it should step aside and let Democrats choose a candidate with the best chance of saving the United States from what they consider the Apocalypse: a second Trump term.

At a time when the world is arguably more beset by danger than at any time for nearly a century, it’s all hands on deck. ‘Biden should step aside, but how?’ demanded the headline of another Sunday article by Times columnist Ross Douthat. “This is a dark moment for Mr. Biden’s presidency,” the Times intoned in an editorial. ‘The combination of Mr. Biden’s age and his absence from the public stage has eroded public trust. It seems as if he is hiding, or worse yet, as if he is hiding.

And the Times isn’t the only one feeling panicked.

Hillary Clinton, who beat Biden for the Democratic nomination in 2016, said her age is a “legitimate issue.”

James Carville, a veteran Democratic strategist who planned Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 campaign, said witheringly that Biden’s absence from a Sunday Super Bowl interview was a sign that his staff had little confidence in him.

The evidence is clear only in the last few days. Last Sunday, Biden confused Francois Mitterrand, French president who died in 1996, with Emmanuel Macron.

Joe Biden, with his wife Jill in 1988, confused the conversations he had had with European leaders

On Wednesday night, during a pair of campaign fundraisers in New York, Biden twice confused conversations he had in 2021 with European leaders at the G7 meeting in Cornwall. In both cases, he said former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who died in 2017, asked him about the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol that took place in 2021.

On Thursday, special counsel Robert Hur, a former top Justice Department official under Trump, delivered the coup de grace. Explaining why the department would not prosecute Biden for mishandling classified documents, he said it was partly because he was a “well-intentioned old man with a bad memory.”

Investigators who questioned Biden said his memory “appeared to have significant limitations” and that he “did not remember, even after several years.” when her son Beau died. (It was in 2015). Biden also did not remember when he was vice president or the details of a debate over sending additional troops to Afghanistan, they said.

Biden quickly compounded the damage by holding a press conference in which he petulantly defended his cognitive powers, only to confuse the presidents of Egypt and Mexico in a conversation about Gaza.

It’s no wonder his White House team, reportedly led by his super-protective wife Jill, preferred not to risk even a few softball questions at the Super Bowl Sunday meeting.

Of course, Robert Hur’s comments about his age and memory would not have had as much impact if the issues he raised had not already been weighing on the minds of American voters.

Repeated polls have shown that both Republicans and Democrats have deep doubts about Biden’s age and his ability to serve a second term. Sleepy Joe, as Trump nicknamed him, is already easily the oldest person to become president in American history. If he takes back the White House, he would be 82 years old at the start of his second term in January 2025 (if Trump wins, he would be 78 years old).

A recent poll showed that a staggering 71 percent of swing state voters — the people most likely to decide the outcome of November’s presidential election — agreed that Biden “is too old to be an effective president.” Another new poll found that 76 percent of all voters are concerned that the president has the physical and mental strength for a second term.

Biden’s long-standing reputation for embarrassing gaffes and misstatements (in 2018 he even described himself as a “gaffe machine”) has benefited him in some ways so far, allowing his team to explain errors as if his Uncle Joe was folksy and stupid. charm.

But the dramatic increase in the frequency of his verbal stumbles is causing alarm. And it has also been accompanied by evidence of physical frailty. Since 2021, he has reportedly tripped eight times while climbing the stairs of Air Force One, the presidential plane, including three times on a single flight to Atlanta.

In 2022 he fell from a bicycle after getting caught in its pedals; in 2023 he stumbled down some small stairs at the G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan; Later that year, he tripped on a sandbag and fell on stage at an Air Force academy graduation ceremony. And when the stairs on Air Force One were shortened last year so he could enter the plane at a lower level, Biden tripped on them, too.

The two brain aneurysms Biden suffered in 1988 were completely treated and, as a result, he showed no signs of mental problems, according to the surgeon who operated on him.

At an annual physical last year, White House physician Kevin O’Connor attributed his stiffness when walking to “significant spinal arthritis, mild post-fracture arthritis of the foot, and mild sensory peripheral neuropathy of the feet.” However, the doctor refused to comment on his mental acuity.

One of Biden’s most frequent mistakes has been referring to Vice President Kamala Harris as ‘president.’ And that, Washington insiders say, may be a Freudian slip.

They believe the main reason Biden intends to run again is because he knows that if he resigns and is succeeded by Harris – widely regarded as useless and even more unpopular than him – the Democrats have an even worse chance of beating Trump.

There is a way out, though: He could hang on, win the party nomination, and then, at the Democratic National Convention in August, announce that he is retiring and won’t endorse a replacement. The convention, made up of party bigwigs rather than the idealistic grassroots who decide primaries, can then elect someone who has a better chance of winning over crucial swing voters and defeating Donald.

That would mean Harris would likely be swept by stronger contenders like California Gov. Gavin Newsom or Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (although both may be too woke for independent voters). Some have not given up hope that Michelle Obama can overcome her many reservations and run.

All this, however, remains an illusion for now. And since it would be very difficult to oust Biden, it’s up to him to play ball. Which brings us back to square one: because privately it is understood that he believes he is the only Democrat who can beat Trump.