Table of Contents

Of the world’s seven richest economies, Japan is the most enigmatic. At a time when the West has degraded its industrial base, Japan is a steel, shipbuilding and car powerhouse. There are few homes in Britain without a Toyota parked nearby, a Sony entertainment system or a computer without Japanese hardware.

The country matters to most of our lives as the ultimate owner of key assets such as brewer Fuller’s, computer systems supplier Fujitsu, fashion brand Uniqlo and the Financial Times newspaper.

However, most Britons would be hard pressed to name the country’s prime minister, Fumio Kishida.

They would also struggle to identify the country’s stock indexes, the Nikkei 225 and the Topix, or recognise its financial importance to the world as a holder of $1.3 trillion (£1 trillion) in dollar assets.

Last week, people in Britain and around the world got a rare glimpse of just how crucial Japan’s £3.4 trillion-a-year economy, the world’s fourth-biggest, is to global finance.

The carry trade: The Bank of Japan’s surprise interest rate decision triggered huge losses for domestic and global investors

When Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), raised interest rates against the advice of the International Monetary Fund and to the surprise of traders around the world, it unleashed chaos. There is already speculation that the BoJ may have more tricks up its sleeve.

As stock markets (which have since recovered) plummeted around the world, the value of our pension funds and savings in shares plummeted. The alarm bells rang and asset managers and private investors rushed to restructure their portfolios.

I received a call from a close relative who was shocked to find that his investments had shrunk by many thousands of pounds while he was sleeping.

The market turmoil has put the spotlight on a country whose culture is a curiosity to most Westerners. Consumerism is eschewed in favour of thrift, even though the country is home to some of the world’s most elegant old-style department stores, such as Matsuzakaya.

Tokyo is a city that never sleeps, with its discreet Michelin-starred restaurants and the bustling nightclubs of Roppongi. Yet it is the cleanest city of all, where you can eat on meticulously maintained streets.

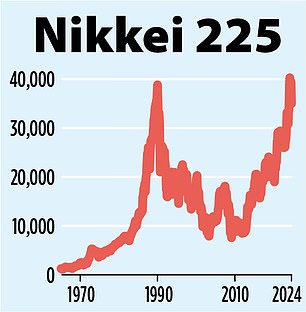

As for the stock market, before the recent crisis it had suffered 34 years of stagnation.

It was only in February this year that the Nikkei index managed to surpass a peak reached in 1989. Finally, the nightmare of the lost decades, which saw stock and property values plummet from peaks reached in the 1970s and 1980s, seemed to be over.

That recovery, which took so long to engineer, was only made possible by Abenomics, a plan unveiled by the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2012, widely seen as an act of homage to Thatcherism.

Faced with an ageing population, disinflation and low growth, Abe’s response was to adopt an activist monetary policy, try to control the growing budget and prioritise growth.

The experiments with quantitative easing, buying Japanese government bonds, corporate bonds and other assets worked so well that America’s most revered investor, Warren Buffett, bought large stakes in five major financial and industrial companies: Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu and Marubeni.

In January of this year, Buffett increased his holdings and other asset managers followed suit.

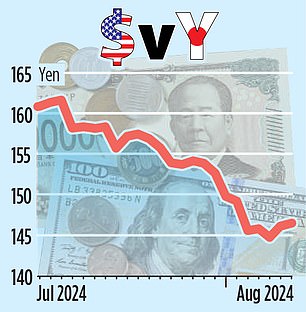

What changed the situation radically was Russia’s war against Ukraine. The US recovery from the sharp rise in inflation and high interest rates left the other G7 countries in the dust and the dollar soared against the yen.

This combination of a weak yen and low borrowing costs in Japan opened up a tempting trading opportunity for hedge funds, arbitrageurs and asset managers around the world. Thus was born the Japanese carry trade. Some $500 billion or more worth of yen was borrowed and invested in high-yielding assets in other markets around the world. What could possibly go wrong?

Suddenly, the situation changed. On July 31, the Bank of Japan changed course and raised its key interest rate to 0.25 percent, from the previous range of 0 to 0.1 percent.

Equally significant was the fact that it outlined a plan to dismantle its massive bond-buying programme after more than a decade of stimulus measures. The era of the cheap yen and ultra-low interest rates was coming to an end. The currency fell more than 2% to 150 yen per dollar for the first time since March this year.

The final straw for the yen carry trade came on Friday, August 2, when the US government reported that the US job creation miracle had stalled in July. The data raised fears that the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, had overdone its fight against inflation and that a recession was looming. The table was set for a powerful implosion when Asian markets reopened early last week.

The shift in sentiment was damaging as investors dumped Nikkei stocks and the carry trade began. Japan’s stock markets suffered their worst drop since the 1987 crash, falling by a staggering 12 percent. The tectonic plates of capitalism shook as investors around the world dumped stocks and bonds. The crisis was short-lived and by midweek a buying frenzy had the Nikkei back to where it had started and more.

In the real economy, where growth and employment are reflected, little had changed. Cars were still rolling off Toyota’s production lines in record numbers. Buffett was selling shares of Apple, not Sumitomo.

The events of the past week will have convinced critics that stock markets are nothing more than giant casinos. Perhaps, but they may force real change. It is now recognised that US interest rates have been too high for too long, creating all sorts of distortions.

Federal Reserve watchers such as Nobel laureate and New York Times commentator Paul Krugman argue that the U.S. central bank must now respond to Tokyo’s warning signal by cutting rates to immediately avert a U.S. and global slowdown.

When governments and central banks act rashly, markets impose severe discipline. The seismic shifts on the Tokyo Stock Exchange may have stabilized, but it is inevitable that some professional and private investors have been crushed in the rush to get out.

DIY INVESTMENT PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investment and ready-to-use portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free investment ideas and fund trading

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat rate investing from £4.99 per month

Saxo

Saxo

Get £200 back in trading commissions

Trade 212

Trade 212

Free treatment and no commissions per account

Affiliate links: If you purchase a product This is Money may earn a commission. These offers are chosen by our editorial team as we believe they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. This helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationships to affect our editorial independence.