When I was 18 years old I got pregnant. The other side denied any involvement, so it must have been one of those “immaculate” things we always learned as Irish kids.

In the 1980s I was living and intending to study in Belfast where things were a bit behind the rest of the world and certainly not being done to produce babies where babies were not expected.

I couldn’t return to the deepest, darkest countryside to live with my parents and work at the local animal feed plant, so I thought I would have to stay and finish my studies. But because I was from the countryside, where women had an idea of themselves as physical forces made of muscles and bones, rather than just pretty skin, I became a bouncer in the Students’ Union at Queen’s University Belfast for a while. . . It was easier to get a babysitter at night than during the day, so my neighbor stayed with the baby while I worked.

She was a lovely old lady who never seemed to sleep and said she enjoyed company; She was either my daughter or a cat, she told me she, and she was allergic to cats.

Every night he was at the doors of one of the bars on the premises. Entry was free for those with a student card and their guests, and door staff were there to stop drink smuggling and general bad behavior. We were not allowed to smile. We also weren’t supposed to lean against the wall, we weren’t supposed to dance or drink.

Maguire: ‘We weren’t allowed to smile’

Drugs were not a problem then in Belfast. I told you we were a little behind on everything else. We had to see everyone having fun and having fun with each other, and with each other’s girlfriends and boyfriends and drinking shots and a lot of whiskey and turning red in the face and… Then, usually around kick time, like When the kids went out of a birthday party, the tantrums began.

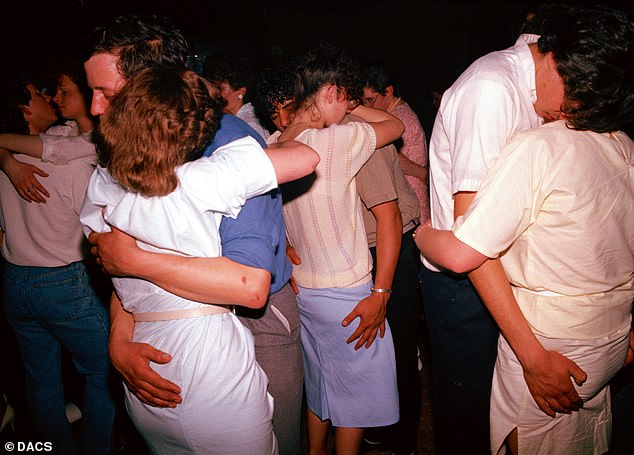

You would watch him finish from a distance and look at the others across the room. Your heart was beating a little faster, your palms were sweating, you cleared your throat to feel a little more encouraged, and you moved a little closer, grateful to see the others coming closer. also, a closed circle of eight or ten black and white photographs in the muggy, smoky darkness before someone turned on the lights.

They stood face to face, then chest to chest, then they pushed, then we were gone, Wild West time, flying chairs and screaming women and a rugby scrum without a referee, right in the middle of the dance floor, pushing forward and back tables, counters and speakers without order or plan.

We, the students’ union door staff, learned that girls in Belfast fight much dirtier than boys.

People backed away but held onto their glasses tightly and drank the last of their drinks in case they lost them in the chaos.

We had to throw ourselves into the melee, put an end to the altercation and expel the two or three offenders. If you were a bouncer you got into boy fights and if you were a bouncer, the idea was that you got into girl fights and the Union wouldn’t be convicted of assault.

The problem was that the Belfast girls fought much dirtier than the Belfast boys. We had been trained for half a day on how to hold people down so they couldn’t throw a punch, but the training hadn’t covered how to hold people down so they couldn’t take a big bite out of your arm or stab you in the instep. with a stiletto heel or poking out your eyeball with your fingernail.

So when it came to a girl fight, we usually all let it wear itself out. The goalie boys stood on the periphery looking embarrassed and we, the goalie girls, ran the circle of hate. The boyfriends also stayed behind, looking scared, and other girls gathered their coats and bags, made disgusted faces, and walked away toward the bathrooms or doors.

In Belfast in the 80s the police were busy elsewhere so pretty much anything goes for students without a terrorism conviction. The worst injury I saw was that of a young man who had been glassed. He had a big jagged cut on his face which he kept holding while blood ran through his fingers, while he said: “No, no, it’s okay, I’ll have another pint, sure, it’ll be great.”

The other goalkeepers were as strange as me, a real mix. Some were there for the uniform, the power and the fights, and these were the ones I avoided, both men and women. You would see their eyes shine, from time to time, with something more than humanity, and you would know that it was not safe to be around them.

They would be the ones to exchange the loot at the end of the night as the gray-faced cleaners pushed mops across the sticky dance floor: knives, keys, bills and whatever else was stolen from the drunken oafs they had kept together in close quarters. . They were the ones who broke bones, smashed faces (that kind of thing) and blamed the gamblers.

Then there were the boys. Without smiling? Regardless of the rules, these bouncers leaned against the door frames with their arms crossed and lazy smiles. They constantly flirted with the punters, repelled the ugly ones and admitted the charming ones, hoping that the subsequent payment would be, at the very least, a smile.

It was the ’80s, remember? No one saw anything wrong with this, except the Ugly Ones, of course, who shivered and shivered outside as they waited for a decent bouncer to come in on duty. Or a blind one.

The Minesweepers were only looking for one thing. Free drink. They raised glasses unattended and drank surreptitiously, and confiscated flasks and quarter bottles of vodders to drink in the bathrooms during their break.

At closing time they wandered around the tables, drinking everything from gin to sex on the beach, with unlit butts in the glass or not. In a fight they were worse than useless: they flailed and fell everywhere.

But on the plus side they tended to have staying power, as they had usually lost the ability to feel pain and simply lay on top of their attackers when their limbs failed: dead weights that allowed the rest of us to have a secure grip.

As co-workers everywhere do, we found our set and stuck to it. I was with the Yuks, who were no one or nothing, they were just there for the job, looking at the clock to find out the closing time and the salary (£3.25 an hour, for 20-25 hours a week).

We didn’t have much to say to each other, but we didn’t have much to say against each other either, so we spent what time we could and waited for ours to come, when we too could drink and roar and jump. around Van Halen and Def Leppard and waking up with a mouth as dry as Gandhi’s flip-flops on a stranger’s bedroom floor.

Now silence reigns where I sit, writing about that youthful noise, that stench and that threat. As soon as my rosy-cheeked baby left me, I took a day job as a classroom assistant and got the hell out of Dodge. I never missed it. Primary school children are loud, unpredictable and sometimes bite, but there is never any force behind it and there is no need to pin them to the ground and bounce their forehead on the ground to get their attention. The same may not be true for high school kids; I’m not in a position to say.

Everything we do remains with us, of course, throughout our varied lives.

The brightly colored girls who scratch and bite are woven into my writings and nightmares over the years, as are the bouncers I stood with along the sweaty, throbbing walls night after night: the misfits, the impoverished and the psychotic, all drawn to work by their demons and all held for that short time in a tight bond of connection against everyone else, against the happy, drunken, careless people of the world.

Roisin Maguire’s first novel night swimmers is published by Serpent’s Tail, £16.99. To order a copy for £14.44 until April 14 with free UK delivery, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.