At school there was always one student who seemed to excel in every subject, from math to literature to music.

Scientists call this phenomenon “general intelligence” or “g factor” and for the first time have found evidence that it also exists in dogs.

Researchers in Budapest, Hungary, recruited more than 100 dogs for various tasks, testing key skills such as memory, learning and problem solving.

They found that rather than simply excelling in one area, the smartest dogs tended to get high scores across the board, as did the school’s top students.

While the g factor in humans is linked to better academic and work performance in life, gifted dogs may be better able to fend for themselves or help humans in a crisis.

Like humans, dogs excel at different tasks involving different cognitive abilities, regardless of breed, the new study shows. In this task from the experiments testing problem solving, dogs had to locate the entrance to a box containing food, when the position of the opening of the box kept moving.

“The study suggests that the structure of dogs’ cognitive abilities is similar to that of humans,” study author Professor Enikő Kubinyi from Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) told MailOnline.

“Dogs have a general intelligence that influences their performance on a range of cognitive tasks in a similar way to that of humans.”

In psychology, the g factor is a “fundamental component of intelligence” and is closely related to academic and career success.

“The concept of ‘g factor’ or general intelligence comes from human psychology,” Professor Kubinyi added.

“It refers to the idea that individual cognitive (mental) performance is based on a single, global cognitive ability that spans different tasks.”

To see if it exists in dogs, the team used seven tasks to evaluate the cognitive performance of 129 domestic dogs between three and 15 years old, over two and a half years.

The sample was made up of 59 mixed breed dogs and 70 purebred dogs from 33 different breeds belonging to families.

Researchers in Budapest, Hungary, recruited more than 100 dogs for various tasks, testing key skills such as memory, learning and problem solving.

In one task, the dogs had to follow a person’s gesture to locate a hidden food reward, while in another, they had to remember which jar the treat was in.

In the pot task, the dogs saw which pot the food had been placed in, but were then distracted by commands or petting and conversation. Dogs with higher intelligence could remember the location of the food later despite the distraction.

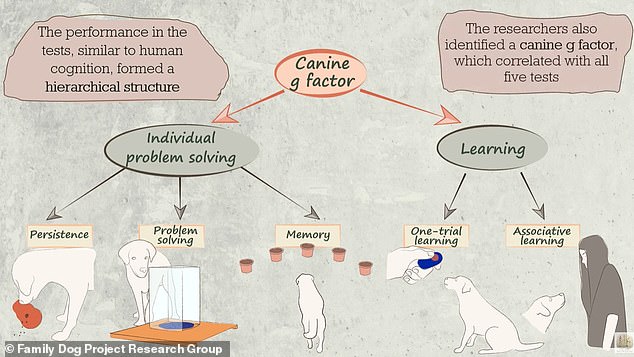

Typically, the tasks assessed learning ability and problem-solving ability (which included tests of memory and “persistence”).

In one task, the dogs had to follow a researcher’s gesture to locate a hidden food reward, while in another, they had to remember which jar contained a treat.

In another task, the canines had to obtain treats from a Kong Wobbler dog toy, which is held upright until they touch it with their paw or nose.

Overall, the researchers found that dogs that performed well on problem-solving tasks also performed well on learning tasks.

This suggests that there is a “general cognitive factor” that unites them, which they call the “canine g factor.”

“The general cognitive factor (g) showed consistency over a period of at least two and a half years,” Professor Kubinyi told MailOnline.

Because of the diversity of dogs used in the experiments (33 different breeds in total), the findings are generalizable to all dogs, he added.

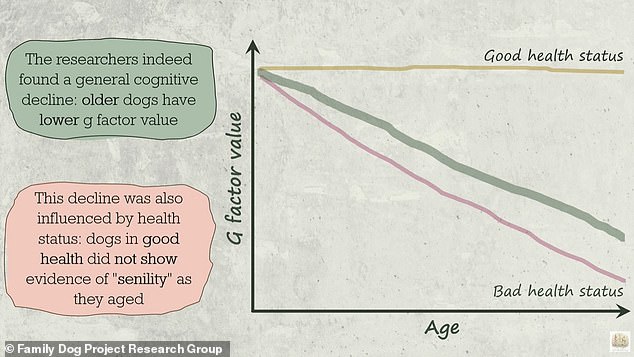

The researchers also found that the dogs’ g factor decreased with age, but only when overall health declined at the same time.

Dogs that continued to be in good health as they aged did not actually suffer a decline in their overall intelligence.

While the g factor in humans is linked to better academic and work performance in life, gifted dogs may be better able to fend for themselves or help humans in a crisis.

The tasks generally assessed learning ability and problem-solving ability (which included memory and “persistence” tests).

The dogs’ g-factor declined increasingly as they aged, but only when their overall health declined at the same time. Dogs that continued to be in good health as they aged did not suffer a decline in overall intelligence

This aging pattern resembles human aging and presents another parallel with that of canines, according to experts, who publish their findings in Geroscience.

“The study provides novel insights into canine cognition, particularly with regard to its structure, stability and the impact of aging and health status,” Professor Kubinyi said.

“Furthermore, it highlights the value and translational relevance of dogs as models for studying human cognition and aging.”

Eötvös Loránd University regularly conducts research into dog behavior, and previous research also suggests that they are incredibly similar to us despite being a completely different order of mammals.

A 2020 study found that both dogs and humans process intonation (how a voice rises and falls) and the meaning of words in different parts of the brain.

Meanwhile, a 2022 study found that they recognize the difference between speech and gibberish and can even distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar languages.