At first it seemed like a simple but tragic accident. Fourteen months after they disappeared in a snowstorm in the mountains of central Italy, the remains of British Jeannette May and her partner Gabriella Guerin were found in a forest ravine by a man who was hunting wild boar.

But far from solving the mystery, the macabre discovery of their decomposed bodies only served to fuel more questions about a case that had gripped the public imagination from the moment they disappeared.

As time passed, speculation moved from one sensational theory to another. The women had been victims of a kidnapping and ransom. They were linked to an international ring of jewel thieves. The Vatican was involved, as was the mafia.

No wonder the suspicion that they had died from something as simple as exposure after getting lost in bad weather was so quickly dismissed.

What fueled this fascination was not only the manifest incompetence of the local police, but also the glamor and backstory of the surprising Mrs. May.

Former model Jeanette May, found dead in 1982 in Italy, had previously been married to international banker Sir Evelyn de Rothschild.

The body of Jeanette May, above, and that of her partner Gabriella Guerin were found by a man hunting birds.

A former model, she had previously been married to international banker Sir Evelyn de Rothschild, financial advisor to Queen Elizabeth, and, interestingly, still used his name.

Now, almost exactly 44 years after she and her friend set out sightseeing in the countryside where Mrs May had bought a holiday home, only to be swallowed up by a blizzard and never seen alive again, Prosecutors dramatically announced that they had been returned. opening your investigation.

Many of those wilder theories, discarded long ago, will surely be aired again. The question is: ‘Why now?’ And what can they hope to discover almost four and a half decades after the tragedy?

The police are coy about their motives, speaking only of finding “aspects worth investigating.”

Detectives have begun reinterviewing witnesses. Among them is hotelier Oretelio Valori, who says he served the women hot drinks and that there was a man waiting for them in a car.

You might think that no one is more important to a re-examination of events than Stephen, Mrs. May’s husband. But I understand that you were not informed of the review of the cold case.

Now 87, the former John Lewis Partnership personnel director refuses to talk about a case that must still be painful for him. How can it not be?

For more than four decades he has had to endure not only the agony of losing his wife of 41 years, but also the morbid curiosity surrounding her disappearance.

The Mays had been married just four years when Jeannette died. They met at a dinner in 1975, four years after Jeannette’s amicable divorce from Rothschild, who had not yet received a knighthood.

Jeannette had worked as an interior decorator but was looking for a change. Stephen, a bachelor, suggested he follow a John Lewis training program and he spent six months in the shoe department of the store in Brent Cross, London. They married the following year.

An only child, Jeannette was nine months old when her RAF sergeant father was killed defusing a German bomb in 1940, and she was raised by her mother Susan. At the age of 16 she dedicated herself to modeling and television work. Photographs from Vogue and other magazines of the time show a beautiful, slender blonde with blue eyes.

Following her divorce from de Rothschild (their marriage ended after five years in 1971), the two maintained a good relationship. This contact would prove vital in the months after his disappearance.

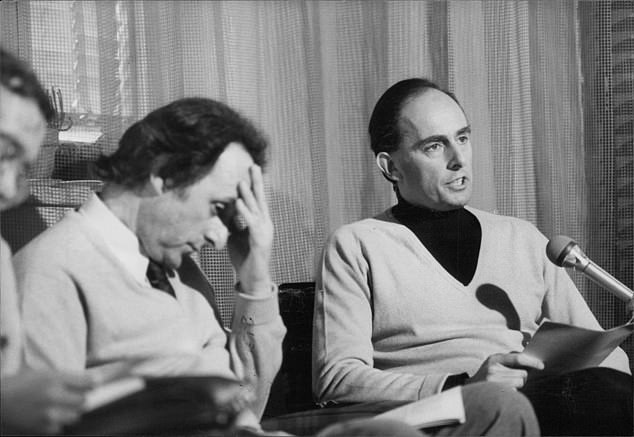

May’s then-husband Stephen May (right) at a press conference in Sarmano, Italy.

In 1979, she and May bought a 300-year-old farmhouse near the medieval town of Sarnano, 225 kilometers northeast of Rome, a renovation project for the couple, who loved the area.

It was in Sarnano that she checked into a hotel in November 1980, signing the register in the name of her first husband that she had kept in her passport.

The objective of the visit was to check the progress of the works on the house with the surveyor Nazzareno Venanzi. He was one of the last people to see her and Mrs. Guerin, her housekeeper during her marriage to de Rothschild, who acted as interpreter.

“We had a snack before lunch, then she asked me if I wanted to accompany them both on the mountain, but I declined because I was busy,” Venanzi later said. “When I found out they weren’t returning to their hotel, I became concerned and notified the police.”

It remains puzzling why the two decided to go on such an outing on the night of November 29. That afternoon a snowstorm began: the heaviest snowfall in the region in 35 years, with drifts up to 3 meters deep.

Stephen May disembarks from a helicopter after searching for his missing wife Jeanette

This house in Schitto, near Sarnano, Italy, was owned by Mr. May and his wife Jeanette.

While the police began to comb the valleys, Stephen May arrived from London. The official opinion was that the women should be sheltered somewhere. But police also harbored some prejudices, suspecting that the women might have been involved in a romantic affair.

The search continued for weeks. Then, on December 18, a helicopter crew spotted the roof of a Peugeot poking out of a pile of snow; The car was empty and locked.

Not far away was a shepherd’s summer hut. When the police forced their way in, there were signs that it had been occupied. Wood had burned in the fireplace and there were dirty dishes. Outside, they had tied a tablecloth to the railing and lit a fire with deck chairs.

The police deduced that the women had sought refuge there. The tablecloth and fire were thought to be an emergency signal.

It was assumed that, since no one came to their aid, the women had gone out on foot and died in the snow. They were confident they would find the bodies when the snow melted. But when spring came there was still no sign of them. Throughout 1981, May traveled to Italy at least once a month, but progress had stalled.

In January 1982, he offered a reward of up to £150,000. Twelve days later the hunter made his discovery. The wild animals had been working and not much was left of their bodies.

Next to the bodies were the women’s bags containing wallets, cash, traveler’s checks and their wristwatches, which had stopped at the same time.

Instead of solving the mystery of their disappearance, the recovery of the bodies made it worse. Was this, after all, a kidnapping gone wrong?

Just a year before Mrs May’s disappearance, British businessman Rolf Schild, his wife and daughter were kidnapped by a gang in Sardinia. They were released after an appeal from the Pope and the payment of a ransom.

The kidnappers had taken the German-born Schild’s name as Rothschild. Was the same methodology used with Mrs May?

But in his case there was no ransom demand. Logic would suggest that any such approach would have been beneficial to the Rothschild family, but Evelyn de Rothschild, Jeannette’s ex-husband who died two years ago at the age of 91, assured May that she had received no such demand.

Meanwhile, an examination of the Peugeot found no snow under the tires, suggesting it had not been snowing when the women parked. And the dirty dishes inside the shepherd’s shelter suggested that more than two people had been present.

Samples of twine were also found near the bodies inside the remote cabin, reinforcing the theory that the women had been tied up and abandoned.

‘Why did the hunters find the bodies in a place that had been searched by the police? “Maybe the police didn’t see them or the bodies were left there later,” said Colonel Raffaele Ruocco, who is working on the new investigation.

Had they been lured to the farm, kidnapped, and subsequently murdered? And what about the mysterious figure seen by the hotelier?

Questions were also raised about a robbery at Christie’s in Rome a day before they disappeared. A fortnight after leaving her hotel in Sarnano, a telegram arrived for Mrs May setting up an appointment at a Rome apartment which police were linking to goods stolen from the sales room.

The police eventually decided that the telegram was a hoax, but (wrongly) linked May’s death to the murder of an Italian, Sergio Vaccari, who was found stabbed to death in an apartment in Holland Park, west London. According to them, he was known in the antiques trade.

Curiously, Vaccari was linked to the murder of Roberto Calvi, the Holy See banker found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge that year, an apparent mafia “hit”.

Sources tell me May has insisted that such links with his wife are absurd. She did not know Vaccari and the connection to the Christie’s robbery was said to be “nonsense.”

Still outlandish theories persisted. One suggested that his wife had been silenced because she had to make accusations against high-ranking members of the Vatican.

In such circumstances, it is not surprising that Stephen May has barely spoken publicly about this disturbing story.

The death of his wife remains a detective novel that, at times, has bordered on farce. She cries out for someone to tie up the loose ends. But after all these years, no one expects this new research to do it.