A woman has revealed how her uncle repeatedly sexually abused her from the age of seven to 13 and sent her Valentine’s cards throughout the abuse.

Elisa Blanco, now 25, was regularly raped and assaulted by Charles Sharkey, 72, until she was a teenager.

He began his campaign of abuse by sending her another Valentine’s card when she was a child, but when she received another “love” note from him at age 22, she decided to tell her story to the police.

Sharkey was sentenced to 15 years in prison last October after being found guilty of four counts of rape, two of causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity, two of sexual assault of a child and one of assaulting a child by penetration.

Now, Elisa bravely gives up her right to anonymity to help other survivors of sexual abuse.

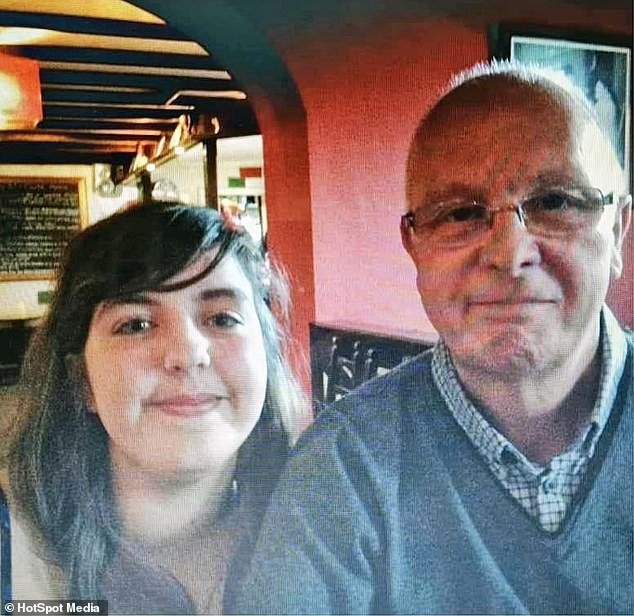

Elisa Blanco (pictured), from Northumberland, bravely gives up her anonymity to tell how her devious uncle sexually abused her when she was between seven and 13 years old.

Elisa, a pastry chef, said: ‘For years, I blamed myself for what my uncle did to me.

‘I want others to know that it is never too late to report bullies. “I’m glad I finally got my justice.”

Sharkey, who was known to his friends and family as Mick, was Elisa’s uncle by marriage and often babysat.

He was like a “second father” to Elisa, and they would both enjoy watching horse racing together.

In February 2006, Elisa, then seven years old, was the only person at school who did not receive a Valentine’s card.

She says: ‘That night, I cried with my parents and with Mick.

‘The next day, they handed me a card through the door. It was a Valentine’s Day card that said: ‘For Elisa, love from ??? xxx’.

‘A few days later, Mick told me he had sent it. I was so happy.’

Even after Charles Sharkey, known as Mick to his friends and family, stopped physically abusing her, he continued to send Elisa disturbing Valentine’s cards (Elisa was 16 with Sharkey).

Elisa (pictured) hopes that by speaking out, she can help other survivors of sexual abuse.

Later that year, Elisa and Sharkey were watching horse racing together in their room, while Elisa’s aunt was downstairs.

He asked Elisa to help him ‘do his needs’.

Recalling it, she said: “I was confused, so he said, ‘I can show you and you can help.’

‘He took off his underwear and started touching himself. Then he took my hand and put it on her private parts.

Elisa said she didn’t understand what was happening. Once she was done, Sharkey said no one was allowed to know.

Elisa added: “I trusted him, so I didn’t question what he had done.”

The following year, Sharkey sent Elisa another Valentine’s Day card, which she said made her feel “really special.”

In 2008, nine-year-old Elisa was in Sharkey’s bedroom when he ordered her to undress.

He then started touching Elisa below, while also touching himself.

Then, months later, Sharkey raped Elisa for the first time.

Elisa bravely reported Sharkey (pictured) when she was 22 and in October last year he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Elisa appears in the photo at the age of seven, when the abuse by her twisted uncle began.

She recalled: ‘He told me it might hurt, and it did. He was so tall and heavy that I couldn’t move.

“I felt very scared, but I let him continue.”

Afterwards, Shakey thanked Elisa and from then on he would rape her every time they were alone.

She said: “I hated it, but I convinced myself it was normal.”

Two years later, in 2011, Elisa was taught about sex education at school and realized what she was previously too young to understand.

She said: ‘I realized what Mick was doing was wrong. His abuse continued until I was 13, when I confronted him.

“Fortunately, it never touched me again.”

But Elisa still had to see Sharkey at family events and keeping the abuse a secret was torture.

Finally, at age 14, she came clean to a school friend, but it would still be years before she worked up the courage to report him.

Elisa appears at the age of five with her uncle before the abuse began; He said he was like a “second father” to her.

In August 2023, Elisa testified bravely behind a screen at Newcastle Crown Court.

She said: “My friend was very shocked and told me to report him, but I wasn’t ready.”

While Elisa tried to avoid Sharkey, he continued sending Valentine’s cards and in February 2014 she received another.

She said: ‘I tore up the card and threw it in the bin. I was so angry. It was like he didn’t want me to leave behind what he had done.”

As the years went by, Elisa became afraid of men and had panic attacks whenever she saw someone who looked or smelled like Sharkey.

Then, one day in 2020, he visited Elisa’s family home.

Elisa said: ‘I stayed upstairs. When Mick left, my mom came up to my room and asked me why she was mad at him. Then my dad showed up and I told them everything.”

Elisa’s parents were horrified.

They asked her if she wanted to report Sharkey, but she wasn’t ready yet. The following year, in February 2021, Elisa, then 22 years old, received another Valentine’s card from her.

Elisa reported Mick in 2021, with the full support of her parents, and said she immediately felt believed by the officers.

Sharkey was found guilty of four counts of rape, two of causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity, two of sexual assault of a child and one of assaulting a child by penetration.

She explains: “A month later, I reported Mick and gave my statement. My parents were very supportive and I immediately felt that the officers believed me.’

Sharkey was arrested but denied the charges.

Elisa said: ‘I knew there would have to be a trial. She was very anxious.’

In August 2023, Elisa bravely testified behind a screen at Newcastle Crown Court.

Sharkey was found guilty of four counts of rape, two of causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity, two of sexual assault of a child and one of assaulting a child by penetration against Elisa.

In October of last year he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Elisa said: ‘When the officer called me to tell me his sentence, I burst into tears. Bringing him to justice made me feel very strong.

“The memories of his abuse have scarred me for life, but at least now everyone knows who my uncle really is.”

If you have been affected by sexual assault and need support, you can call the rape crisis hotline on 0808 500 2222.