Do you enjoy eating a big plate of pasta topped with a small mound of cheese?

You may be surprised to see what a “real” serving of both foods looks like.

Serving suggestions say we should cook only 75g of pasta, which is two or three tablespoons.

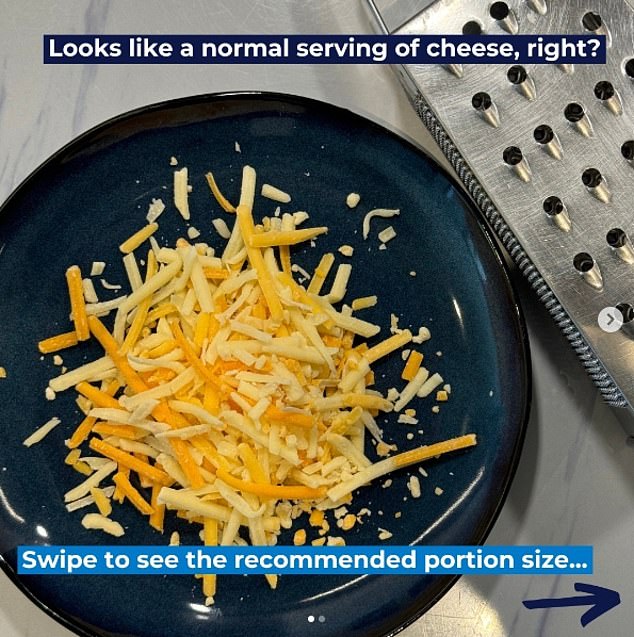

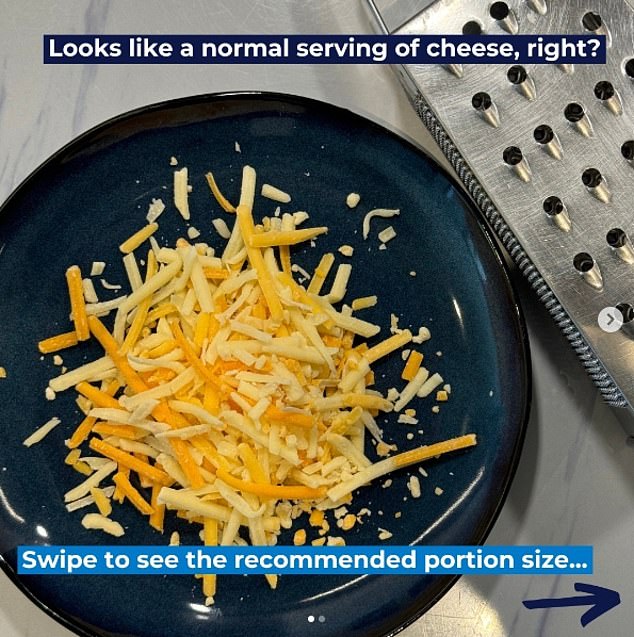

And when it comes to cheese, an actual serving is about 30g, the equivalent of a matchbox-sized block of cheddar.

Private healthcare provider Bupa shared recommended portion sizes for numerous foods on its Instagram, sending social media users into a frenzy.

Many of us fill our plates with pasta, but Bupa says we should eat half this amount of starchy foods in a single meal.

Although 75g of pasta seems like a small amount, this is only the suggested portion for one meal and once cooked the same pasta will weigh 150g and contain around 300 calories.

Some questioned whether the posts were an April Fool’s joke, while others criticized the recommendations for being too small and said more active people might need larger portions.

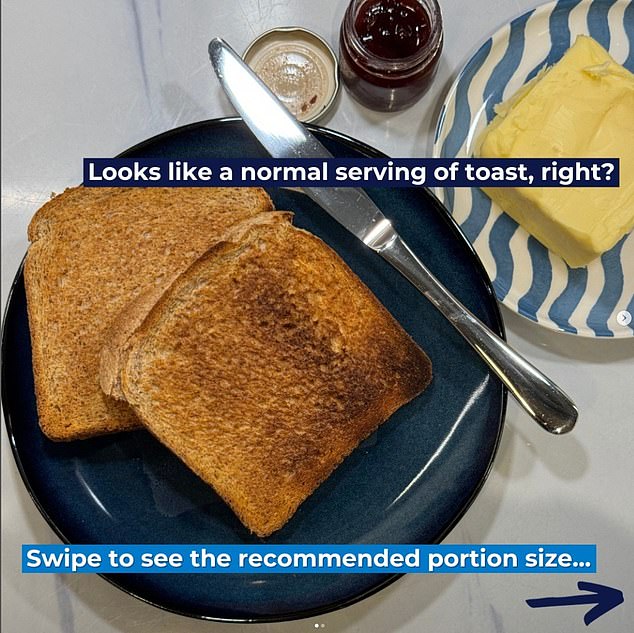

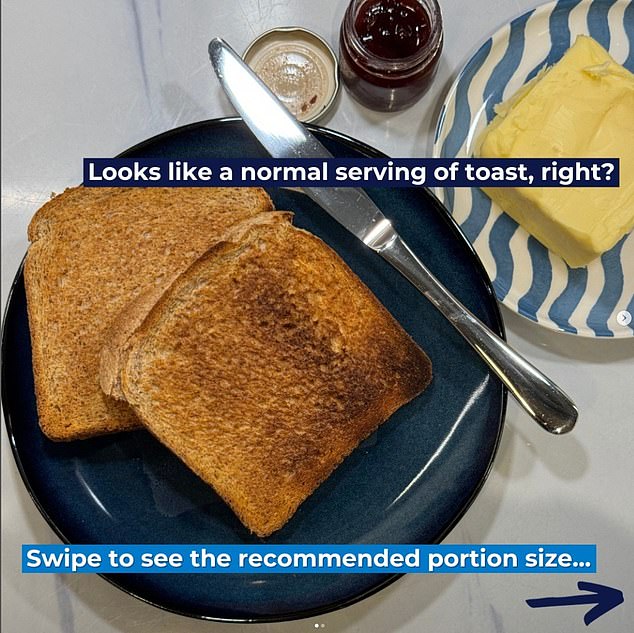

According to recommendations, even two slices of toast for breakfast are too much.

Instead, we should eat just a medium slice of toast.

The average woman is recommended to consume 2,000 calories per day to maintain a healthy weight. Men should be limited to 2,500 or less.

Both pasta and bread are foods rich in starch, one of our main sources of energy.

Grating an entire plate of cheese may be what you would normally do, but Bupa recommends much less.

While a serving of cheese should only be 30g (125 calories) and you should only consume moderate amounts of dairy, according to Bupa you can eat two to three servings a day.

Although 75g of pasta seems like a small amount, this is only the suggested portion for one meal, and once cooked the same pasta will be 150g and contain around 300 calories.

A slice of whole wheat bread is equivalent to about 35 g (120 calories).

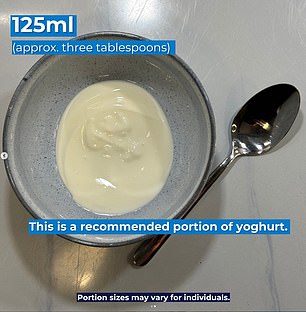

Both cheese and yogurt are good sources of calcium, which helps maintain healthy bones and teeth. They are also a source of protein, says Bupa.

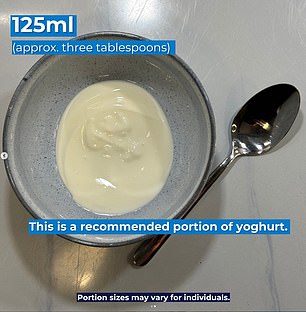

But the healthcare company says you should only eat three tablespoons of yogurt or 125 ml. Plain yogurt packets also suggest eating 100g, which is about 100 calories.

While a serving of cheese should only be 30g (125 calories) and you should only consume moderate amounts of dairy products, Bupa says you can eat two to three servings a day.

Eating two slices of toast has about 240 calories without adding butter or jam, but Bupa says this is not the recommended serving size.

A slice of whole wheat bread has about 35g (120 calories) and this is the recommended amount of bread per serving according to Bupa.

This might look like a matchbox of cheese, a glass of milk, and three tablespoons of yogurt.

But it’s not just starchy foods and dairy products that receive a recommended serving, but also fruit.

In fact, if you thought you’d get one of your five a day by eating a kiwi, you’d be wrong.

Bupa suggests eating two kiwis (80g) to get one serving of fruit.

That’s the same serving recommended for plums, apricots, and satsumas.

According to Bupa, eating half a cup of yogurt is well above the suggested serving size. You should only eat three tablespoons of yogurt or 125ml. Plain yogurt packets also suggest eating 100g, which is about 100 calories.

Eating just one kiwi is not a serving, in this case you will have to eat more to get one of the five a day. Bupa suggests eating two kiwis (80g) to get one serving of fruit. That’s the same serving recommended for plums, apricots, and satsumas.

However, you can also eat too much fruit.

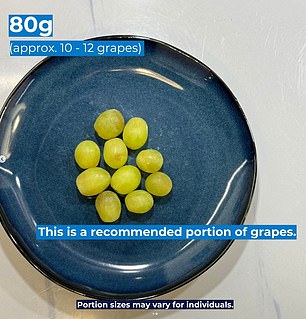

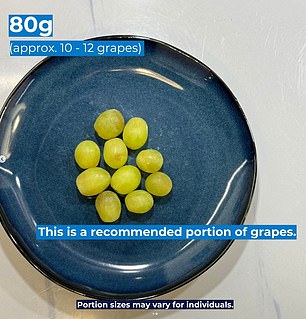

According to Bupa, eating half a box of grapes is too much and we should also limit ourselves to 80g instead, which is equivalent to between 10 and 12 grapes.

For nuts the rules are slightly different and for one of the five a day you should eat 30g and not 80g, which is approximately equivalent to a tablespoon.

“There are always challenges when it comes to providing advice on portion sizes, as food preferences and energy needs vary so much,” said registered dietitian Dr. Duane Mellor.

Agreed that the serving sizes seem accurate, but for an adult following a reduced-calorie diet to help control weight.

Bupa suggests that it is possible to eat too much fruit and instead limit yourself to 80g portions. According to Bupa, eating half a box of grapes is too much and instead we should also limit ourselves to 80g, which is between 10 and 12 grapes.

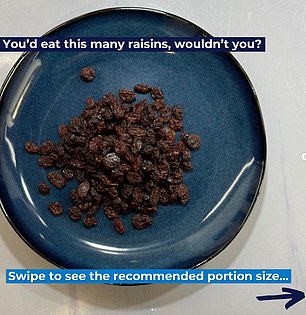

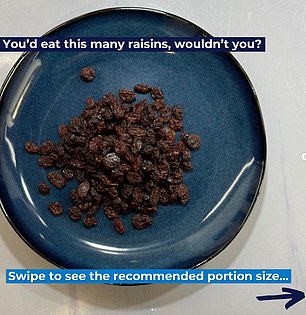

If your portion of raisins usually looks like this, Bupa suggests you should consider reducing it. For nuts, the rules are slightly different and for one of your five a day you should eat 30g, not 80g, which is about a tablespoon.

“In many adults this would lead to weight loss,” he said.

Dr Mellor also said the posts could be “unhelpful” and cause “confusion”.

He said: “Most pasta bags would agree that a typical serving of pasta is 75g of raw pasta.”

“But again, the amount of energy people need varies.

“It’s also not always good to look at individual foods and not observe a healthy dietary pattern across a meal or the entire day, so servings of individual foods can be confusing and unhelpful.”

Niamh Hennessy, chief dietitian at Bupa, said: ‘We encourage healthy eating habits, including industry recommended portion sizes.

“Serving sizes vary from person to person depending on the individual’s age, weight and height, gender, health and activity levels.”