A dog owner received a hostile letter from her neighbors about her pet’s barking, but she doesn’t think it’s as bad as they say.

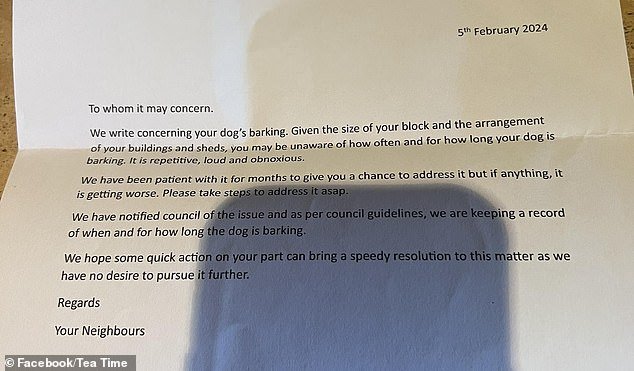

The woman, from Adelaide, received a typed letter from an unknown group of neighbors saying they had run out of patience with the rescue dog’s “repetitive, loud and unpleasant” barking.

But while neighbors claim her dog barks “constantly” during the day, she said this seems “strange” since she doesn’t leave him home alone for long.

“Given the size of your block and the layout of your buildings and sheds, you may not know how often and for how long your dog barks,” the letter said.

“We have been patient for months to give you a chance to fix it, but if anything, it is getting worse. Please take steps to fix it as soon as possible.”

A pet owner asked for help after receiving a hostile letter from a neighbor complaining about her dog’s “repetitive, loud and unpleasant” barking.

Neighbors said they notified the council about the problem and are keeping a record of when and how long the dog barks.

“We hope that quick action on your part can bring a quick resolution to this matter, as we have no desire to move forward,” the letter concludes.

The woman did not know how to approach the problem. She has two dogs, one of which she has almost completely stopped barking since she adopted him.

“The dog is a rescue and his barking has decreased significantly compared to when I got him, 85 percent better than he was originally,” the woman said in a Facebook post. mail.

She said her dogs are not left home alone for more than five or six hours at a time and that when she is inside, they sleep quietly in a crate in her room.

The animal lover said her dogs are not left home alone for more than five or six hours at a time and when she is inside, they sleep quietly in a cage in her room.

“It seems strange when they say it’s constant, but I’m home most of the time outside of work and they’re not barking right now.” Also, they don’t give me the exact time it happens so I can address it,” the owner said.

The dog lover called the city council, who informed her that no noise complaints had been made on her property.

“They think the letter is just a warning, so I’m going to try to fix the problem with a camera and a bark collar,” he said.

“I feel like I take good care of my dogs, but maybe I’ll take more preventive measures to keep the peace.”

The dilemma divided people in the comments: some suggested the neighbor targeted the wrong house, while others thought the woman didn’t know how much her dogs really barked.

‘Is it possible that it’s someone else’s dog and they just think it’s yours? It might be worth getting a camera or two just to see if he is your dog, they may be exaggerating by saying he is constant,” one woman suggested.

‘Maybe in those five or six hours straight, the dog is anxious and barks constantly. Our dog used to be like this. The moment we left her, they started barking,” another explained.

But the woman said she had done “tests” to see if her dog, who had separation anxiety, would bark when she was not home.

‘I sat around the corner in my car and listened, walked around the other block and sat in the park. “I asked my neighbors on the other side to let me know if he barks and I told them if he does, please tell me,” she said.

“No one has complained that I’m in direct contact with him and he hasn’t made a sound, so it’s strange.” He barks, but he plays with my other dog and alerts people when he’s around.’

Dr Cristy Secombe, Head of Veterinary Policy and Advocacy at the Australian Veterinary Association, told FEMAIL that while barking is a normal way dogs communicate with others, owners should actively try to get to the root of it. why your pets bark. Then it can be resolved.

“Dogs typically bark to get attention, during play, hunting, herding, territorial defense, threatening displays, and situations of fear and anxiety,” he said.

‘Understanding why your dog barks is essential to controlling barking problems, which is the most common complaint we hear from dog owners.

‘It is not uncommon for excessive barking to be accompanied by other environmental or behavioral problems. In these situations, it is recommended to consult your veterinarian, who can offer advice on how to manage any behavioral problems that could be contributing.