- Brandon Herrera recreates the assassinations of JFK, MLK and Abraham Lincoln online with fake blood while destroying fake brains with his hands

- Herrera cites the current congressman’s vote on gun control after the Uvalde school massacre as the reason he is running

- Second electoral round scheduled for May 28

<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

A pro-gun YouTuber known for reenacting the assassinations of U.S. presidents online is a challenger for the Texas congressional district that covers Uvalde, the site of one of the worst school shootings in the country’s history.

Rep. Tony Gonzales, who currently holds the seat, fell short in Tuesday’s primary.

He will now face Brandon Herrera in the May primary runoff.

Gonzales is a moderate Republican who voted in favor of gun control after the horrific Uvalde school massacre in 2022.

But in a sign of the area’s unwavering support for the Second Amendment, now Herrera is challenging it.

Texas congressional candidate and Second Amendment fanatic Brandon Herrera has 3.2 million followers on YouTube, where he reenacts the assassinations of President Abraham Lincoln, JFK, and MLK.

In the Lincoln assassination YouTube video he recreated, congressional candidate Brandon Herrera smashed a fake skull that was supposed to represent Lincoln’s head and removed the brain, squeezing out fake blood.

Rep. Tony Gonzales, R-Texas, center, speaking at a press conference on the steps of the Capitol in Washington, DC in July 2021.

Salvador Ramos, 18, killed 19 students and two teachers – and injured 17 others – at Texas City’s Robb Elementary School during the May 24 attack.

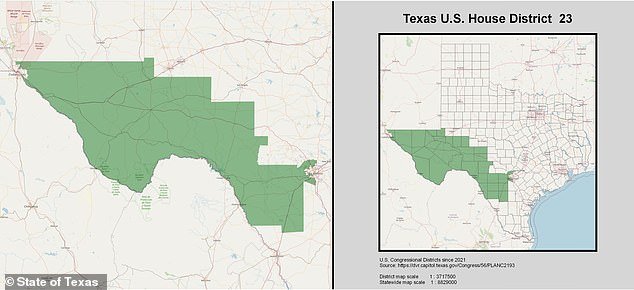

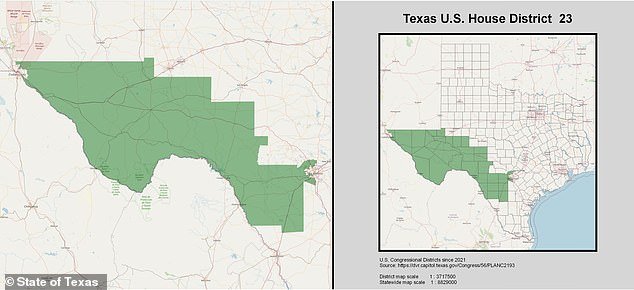

Texas’ 23rd Congressional District is home to Uvalde, a South Texas city where parents still mourn the loss of 19 children and two teachers who were killed by a gunman at Robb Elementary School on May 24, 2022.

The fourth-grade students had their heads blown off their bodies after being shot with an AR-15-style rifle that killer Salvador Ramos purchased legally a few days after his 18th birthday.

Parents of children who survived the horror by covering themselves in the blood of their dead companion will be able to vote in this election.

While Uvalde and the surrounding towns are known as a hunter’s dream and typically very gun friendly, some locals have called for gun control after the tragedy.

Gonzales voted for a bipartisan 2022 bill that provides funding to states with “red flag” laws that allow judges to take firearms away from people who pose an immediate danger to themselves or others and has improved checks. of background information for the sale of weapons.

Heartbreaking footage shows distraught Uvalde students with blood-soaked hair and clothing fleeing Robb Elementary School on the school bus as a girl tearfully tells police how she tried not to cry while calling 911 to report a shooting massive.

Brandon Herrera, a gun fanatic who has more than three million followers on YouTube, boasted online about having testified against the ATF, the federal gun control agency.

The 23rd Congressional District in Texas includes Uvalde and approximately 400 miles of the United States border with Mexico. Migrant crossing hotspots like Eagle Pass and El Paso are also part of the district.

And the moderate Republican paid for it.

As a result, the Texas Republican Party voted to censure Gonzales, even though the congressman is an outspoken critic of the Biden Administration and rails against the president’s border policies on a daily basis.

However, the vast congressional headquarters, which stretches from San Antonio to El Paso, is also home to many border communities, including migrant crossing hotspots like Eagle Pass, Del Rio and El Paso.

Voters there traditionally lean Democratic, which could be an uphill battle for Herrera, who has little recognition among locals despite his army of followers and online notoriety.

Herrera has also called for ending the ATF’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

The federal agency is in charge of gun regulation.

This could be a tough sell to the many federal agents and military personnel who live in the district.

Neither Herrera nor Gonzales’ campaigns responded to a request for comment.