From camouflage to venom, animals have developed dozens of ingenious ways to avoid being eaten.

However, researchers have now discovered that the Japanese eel has an ability that takes escaping the jaws of death to a whole new level.

An incredible video shows the shocking moment an eel “flips” out of its predator’s stomach after being devoured.

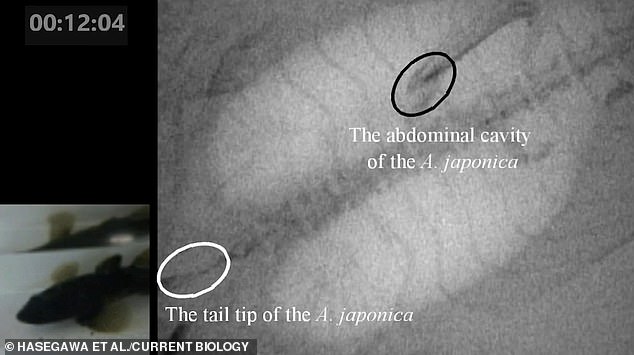

Scientists at Nagasaki University have developed a new X-ray video method to capture the first images showing how eels gain freedom by slipping through the gills of a fish.

Lead researcher Professor Yuuki Kawabata told MailOnline: “Contrary to our expectations, witnessing the eels’ desperate escape from the predator’s stomach to its gills was truly astonishing to us.”

Researchers at Nagasaki University have captured a bizarre X-ray video showing juvenile eels escaping from inside the stomachs of their predators.

In a previous study, Professor Kawabata and her colleagues had already observed that some juvenile Japanese eels were able to escape from the stomachs of other fish.

However, until now they had no idea how the eels managed this strange feat of escape.

Researchers spent a year developing a new X-ray videography method to see what was actually happening to the eel inside the fish’s stomach.

The eels were injected with a contrast agent called barium sulphate, allowing their thin bones to show up on an X-ray of the fish’s interior.

During the experiment, 32 juvenile eels were injected with this chemical before being fed to a native predatory fish called the “dark sleeper” or odontobutis obscura.

Like many predatory fish, the dark dreamfish swallows its prey whole along with the surrounding water by rapidly opening its mouth.

Researchers had observed that Japanese eels (pictured) were able to escape from the stomachs of their predators, but until now they did not know how this was possible.

Once inside, the prey is deposited in the stomach where it dies due to the acidic and oxygen-free environment in an average of 211 seconds.

However, images taken inside the fish’s stomach showed this was not the case.

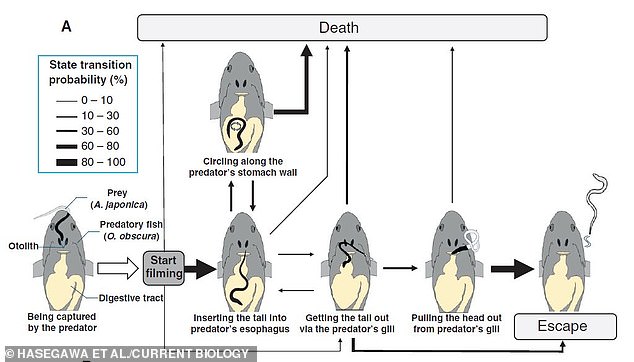

Before the experiment, Professor Kawabata says they expected the eels to try to escape directly from the predator’s mouth into its gills.

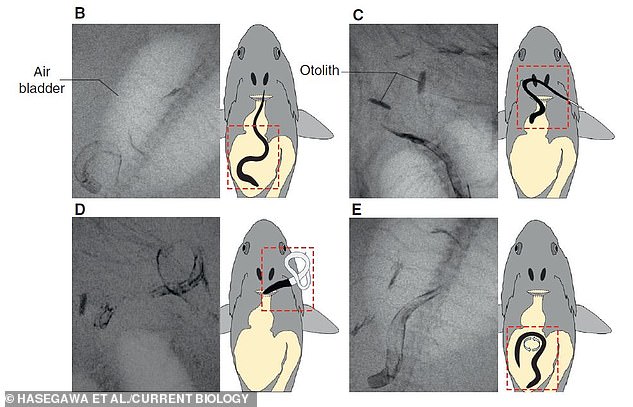

Professor Kawabata says: “The most surprising moment of this study was when we saw the first images of escaping eels moving back up the digestive tract towards the gills of the predatory fish.”

Instead of heading toward the mouth, the researchers observed that the eels forced their tails down the esophagus and directly toward the gills.

From there, the eels coiled their bodies to release their heads and swim away.

Researchers observed some eels circling the fish’s stomach. Of the eels tested, 13 managed to insert their tails through the gills and nine managed to escape completely.

‘We have discovered a unique defensive tactic of juvenile Japanese eels using an X-ray video system: they escape from the predator’s stomach by moving up the digestive tract towards the gills after being captured by the predatory fish.’

In their paper, published in Current Biology, the researchers suggest that the eels’ long bodies make it more likely that their tails will remain protruding into the esophagus.

Of the 32 eels tested, all but four attempted to escape the fish’s digestive tract; 13 managed to detach their tails and nine managed to escape completely.

On average, the eels were able to escape the dark sleeper’s gills just 56 seconds after being swallowed.

Several eels also displayed circling behavior during which they ran around the stomach of the predatory fish as if looking for an exit.

Thirty-two eels were injected with barium sulphate so they could be seen in X-rays and then fed to a native predatory fish called a “dark sleeper” (pictured).

However, only those eels that managed to insert their tail through the esophagus managed to avoid death.

Researchers note that the fish appear to be aware that their prey is trying to escape and will often try to fight back.

Co-author Yuha Hasegawa told MailOnline: ‘Many predatory fish exhibit resistance behaviour by swallowing the escaping eel again, during which they draw water into their mouths and expel it through their gills.

‘The eels could take advantage of this water flow to successfully escape through the predator’s gills.’

However, the predatory fish do not appear to be harmed by the escape attempt.

Using an X-ray camera, researchers discovered that the eel inserted its tail into the fish’s esophagus before exiting through the gills.

Because larger eels were able to escape more frequently, the researchers believe it may be critical for young eels to quickly develop the strength and locomotor skills they need to escape.

Dr Hasegawa says: “This discovery has provided us with new insights: muscle strength and tolerance to highly acidic and anaerobic environments, as well as their elongated and slippery morphology, are necessary for eels to quickly escape the digestive tract before being digested.”

In the future, researchers hope this X-ray technology will be useful for further investigation into how prey manage to escape after being eaten.