For Bea, it was moments like finding herself reading the news in the bathroom that made her feel the need to reevaluate her relationship with her phone.

The 37-year-old Londoner had begun to feel uncomfortable with the way ping notifications and the need to pick up the phone invaded her life. So when her iPhone broke more than a year ago, she decided it was time to switch to a device that would allow her to stay in touch with other people while minimizing distractions.

Bea, who has two young children, opted for a Nokia 2720 Flip, a phone that is billed as “a modern version of the classic flip phone.” She made her decision after reading research on the impact of screen use on children. “I found myself breaking every rule I had about them, surfing and scrolling,” she said. “She had crossed a line; she didn’t want them to think that this is a normal way to go through life, even if it is common.”

Another trigger was learning more about the ways in which smartphones and social media had been designed to be addictive. “I felt a surge of anger because these people had to make decisions about how I spend my life every day,” she said.

Almost two decades after the launch of the first iPhone, a trend for lower-tech devices seems to be taking shape, with a growing minority trade their smartphones for “dumb phones” (or, perhaps in Bea’s case, dumb ones)Ahem The telephones. “I chose this one because it has WhatsApp; it’s too complicated to live life without it,” he said.

With new models like the Boring Phone, the trend is driven in part by young people’s distrust of the data collection and care technology they grew up with, as well as a push to live more offline. And while smartphones are the obvious target of this trend, the “newtro” movement (a combination of “new” and “retro”) is heralding a resurgence of analog media, including cassettes and zines, in the context of the lasting and much -announced vinyl boom.

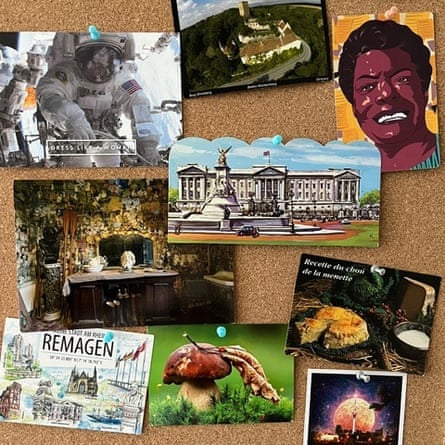

While Jess Perriam, 39, had grown tired of her Instagram account, she knew she wanted to maintain a window into the lives of others. He then turned to Postcrossing, a site that connects people who want to send and receive postcards from strangers around the world. “I still wanted to have that connection with people and learn more about different cultures, but not necessarily while being aggressively promoted,” he said, adding that he receives “tons of reading recommendations” through the publication.

Community It has more than 800,000 members. in 207 countries, with 77 million postcards received since its launch in 2005. While its fastest growth occurred in the early 2010s, it lasted through the pandemic and 400,000 cards are published each month.

While the hobby is reasonably affordable in Australia, where Perriam lives, he notes that the cost of stamps has become prohibitively expensive in other countries he has visited. In addition to writing to people she has never met, she also corresponds with an old friend in the United States. When she sits down with a cup of coffee, Perriam feels like she can hold a thoughtful conversation. “She forces me to sit down and think: what do I want to communicate to my friend? What are the headlines, what things would you like to hear?”

The couple began this correspondence years ago, when Perriam’s friend lived in West Africa. “You feel like you can really bring someone up to speed – she was able to share snippets of her daily life in Benin. Now I have a collection of letters that are a memory of her from her time (there), and there is someone who really understood her.

“There’s something really special about the physical evidence of our lives in each other’s letters,” Perriam added. “(There is) material evidence of a friendship to remember: we have built a history that is really tangible.”

Touch and other physical senses are also important to David Sax, author of The revenge of analog. “We are haptic,” he said. “One of the benefits of analog is its tactility: things you can use, touch, taste and feel. There was an assumption that we would live in a digital future… The pandemic experience showed us a truth that we somewhat minimize: we have bodies that exist in the physical world and we need to go places and touch things. “We want more of the world than is available in 20cm of glass.”

Sax said the appeal of analog is here to stay, pointing to vinyl, film camera sales and the resilience of paper books, but also the post-pandemic rise in in-person experiences such as live music events and the trips. But he doesn’t see it as a reaction against the invasion of technology into our daily lives; He says most people who are embracing the low-tech movement are also using new digital technology when it is convenient and effective. Rather, it is “a counterweight to this which has become the default mode for many things in life.”

Rather than being a purely nostalgic reflection, those who use their smartphone camera are often not from the generation that grew up using analog technology, Sax noted. “The driving market for the Fujifilm Instax (instant camera) is teenagers. “The number one selling albums are Taylor Swift,” she said. “It’s the younger generations who are driving the change; older generations who grew up with analog are nostalgic, but often captivated by the magic of digital technology.”

For Andreas Nygren, a 25-year-old student from Tallinn, the physical nature of film is partly what attracts him more than digital photography. “With analogue, you have to engage much more closely with what’s happening – you’re much more in touch with the environment and the light,” Nygren said.

Nygren has also experimented with ditching social media and a smartphone entirely, but has found it difficult to stay in touch with friends and for college projects. “When you’re not active or messaging, people just forget about you and don’t invite you to anything,” she said. Instead, she is trying to bypass most social media platforms in favor of SMS and WhatsApp messaging. “It’s about intentionality: you’re not just tapping and scrolling, you’re thinking about saying something to a specific person.”

Over time, he noted how over-reliance on digital technology had made him feel distant from the physical world. “It reduces the vitality of life and makes you feel like you are floating in a daze. It’s like being trapped in a cave staring at a wall of shadows, instead of being out in the world. “The analog (trend) is really just an effort to counteract that and recapture embodied reality.”