China has made spaceflight history again when its lunar lander returns to Earth with the first samples of rocks from the far side of the Moon.

The Chinese lunar probe Chang’e-6 landed in China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region at 06:07 GMT (14:07 Beijing time) this morning.

Chang’e-6 brought its precious cargo back to Earth after a months-long journey to the largely unexplored far side of the Moon.

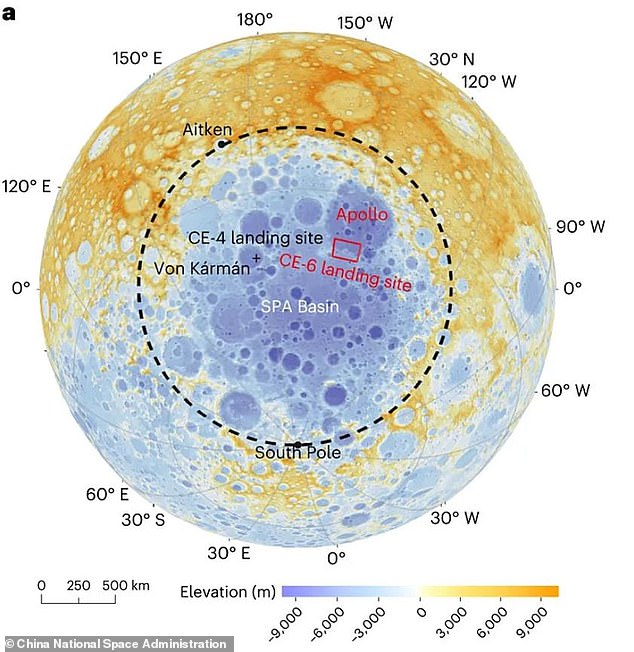

It returned with up to 4.4 pounds (2 kg) of rocky lunar regolith collected by drill from the moon’s South Pole Aitken Basin.

Scientists eagerly await the opportunity to study these samples that could reveal vital clues about the early history of the solar system.

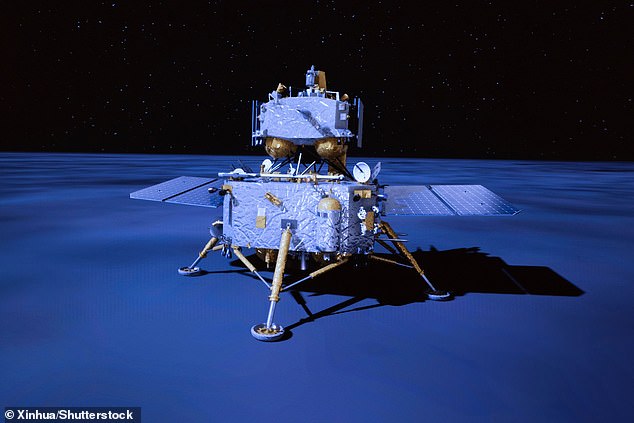

The Chinese Chang’e-6 lander (pictured) has returned to Earth with the first rock samples from the far side of the Moon.

The lander has collected about 4.4 pounds (2 kg) of rocks and regolith from the lunar surface which it has now transported safely to Earth.

After the spacecraft landed by parachute in Inner Mongolia, a team of scientists reached the module within minutes.

“I now declare that the Chang’e 6 lunar exploration mission has achieved complete success,” Zhang Kejian, director of the China National Space Administration, said shortly after landing in a televised news conference.

China’s leader Xi Jinping sent a congratulatory message to the Chang’e team, saying it was a “historic achievement in our country’s efforts to become a space and technological power.”

According to CCTV, a state broadcaster, the samples will be flown to Beijing to remove the sample container and its contents.

Chang’e-6 collected rocks from the Moon’s South Pole Aitken Basin, a crater believed to have formed more than 4 billion years ago.

After collecting the samples, the ascender module (pictured) detached from the lander and returned to lunar orbit.

These samples are of particular scientific importance because they are the first to be collected in the South Pole’s Aitken Basin.

This 2,500-kilometer (1,600-mile) wide volcano is believed to have formed 4.26 billion years ago.

That makes it hundreds of millions of years earlier than many of the other craters on the lunar surface that formed in an event called the “late strong bombardment.”

The samples could reveal more about the moon’s early formation and also show whether there is enough water at the lunar south pole to support human colonies.

“They are expected to answer one of the most fundamental scientific questions in lunar science research: what geological activity is responsible for the differences between the two sides?” said Zongyu Yue, a geologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Chinese scientists are expected to conduct initial analysis of the samples before sharing data and collaborating with international researchers.

Chang’e-6 consists of four main components: the lander, the return capsule, an orbiter and a small rocket carried to the moon called an ascender.

The probe took off from Earth on March 3 aboard a Chinese Long March rocket that carried it into lunar orbit.

On June 1, the orbiter and lander modules separated and the spacecraft made its perilous descent to the lunar surface.

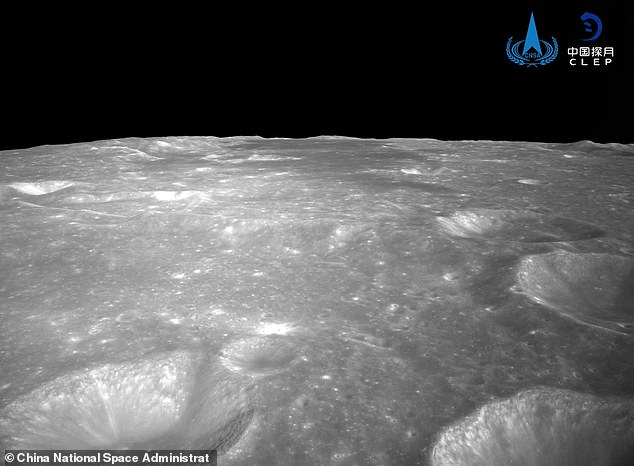

The samples (pictured during collection) could offer scientists insight into the early formation of the solar system.

After successfully making a soft landing near the moon’s south pole, the spacecraft used a drill and shovel to collect rock and regolith samples.

These samples were then launched back into orbit aboard the ascender which rendezvoused with the orbiter on June 6 and began the return journey to Earth on June 21.

This mission was particularly technically challenging because no radio signals from Earth can directly reach the far side of the Moon, a largely unexplored region of the Moon.

Because the Moon is “tidally locked” to the Earth, it rotates in exactly the same time it takes to orbit the Earth.

This causes one side of the moon to be permanently facing away from the planet, although it is not permanently dark as the misnomer “dark side of the moon” might suggest.

Since the far side of the Moon (photographed by Chang’e-6) has no tectonic plates, the ancient craters provide a window into how the planet formed.

To reach the other side, signals must be sent through a relay satellite that must be placed in lunar orbit before landing.

Chang’e-6 received its control signals through Queqiao-2, a 1,200 kg (2,645 lb) relay satellite launched into orbit in March to bounce signals back to Earth.

This is the sixth of eight missions in China’s ambitious lunar program and the second time the nation has placed a lander on the far side of the Moon, but this first mission did not return to Earth.

Looking ahead, the country plans to launch Chang’e-7 in 2026 and Chang’e-8 in 2028.

Chang’e-8 will test the technologies needed to establish a manned base at the Moon’s south pole by the 2030s.

Since this region of the moon is believed to be rich in frozen water, there is a growing space race between nations seeking to establish a permanent presence.

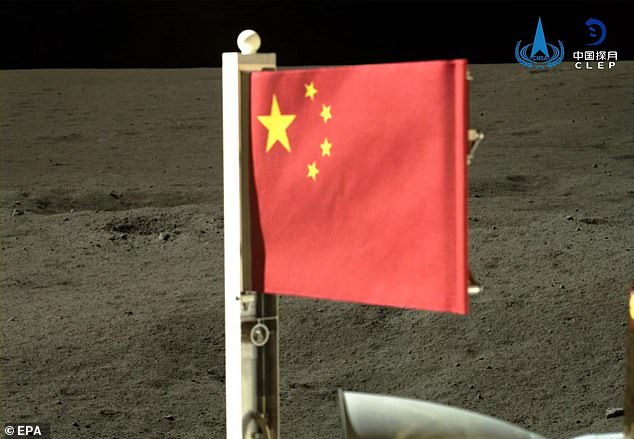

During the mission, Chang’e-6 also flew a Chinese flag made of basalt volcanic rock fibers that could last on the moon for 10,000 years.

Chang’e-6 also highlighted some technologies that could pave the way for the base-building ambition.

Before taking off back to Earth, the lander flew a Chinese flag made of basalt volcanic rock fibers that could potentially last on the Moon for 10,000 years, according to the Chinese National Space Agency.

These fibers are created by heating and stretching rocks similar to those found on the moon and are resistant to corrosion and heat.

Professor Zhou Changyi, one of the rover’s designers, told state broadcasters: “In the future, these basalt fibers can also be used on the Moon to make other things.”

Unlike the flags placed during the Apollo missions, the Chang’e 6 A small flag emerged on a retractable arm deployed from the side of the lunar lander and was not placed on the lunar soil, according to an animation of the mission released by the agency.