One of the leading advocates for an Indigenous voice in Parliament has described Australia as a “nation frozen in time” in an attempt to explain what went wrong during the historic referendum campaign.

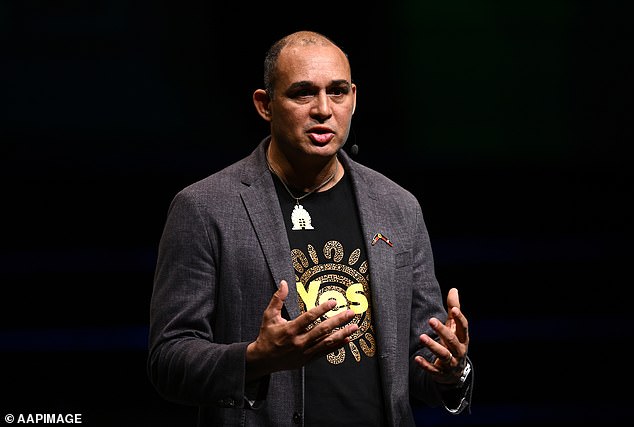

Thomas Mayo was one of the most divisive figures throughout the campaign, with critics seizing on previous comments he had made linking the Voice to the treaty and truth in the early days as examples of the potential risks associated with the proposal.

Now, almost a month after referendum night, in which 60 per cent of Australia and all six states voted against the proposal, Mayo has sought to explain the result on the world stage.

Speaking to the UK’s BBC ‘The Inquiry’ podcast, Mayo put the blame squarely on the opposition for his decision to oppose The Voice.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had committed to One Voice from the moment he took the top job, and his supporters say the Opposition politicized the proposal to score low-level political points.

Thomas Mayo was one of the most divisive figures throughout the campaign, with critics seizing on previous comments he had made linking the Voice to the treaty and truth in the early days as examples of the potential risks associated with the proposal.

“We were fighting on many fronts, but the ultimate destruction of the opportunity came when the opposition decided to go against it,” he told host David Baker.

“No referendum has ever won in this country without bipartisan support, especially since they fought it so strongly and vehemently.”

Mayo acknowledged that Yes campaigns failed to convey clear and concise messages, a fact that confused voters and, in some cases, led them to seek information from the No camp.

Now, as a result of the decisive no vote on October 14, Mayo describes Australia as “a nation frozen in time.”

“(It’s) not a good place for indigenous people,” he said.

‘This is not a good thing for our country. “We need to analyze why this referendum, which was so important for national interests, failed.”

There were tears and strong emotions on the night of the referendum as Yes supporters realized, very quickly, that there was no path to victory.

Pictured: A Yes supporter reacts at the official Yes campaign event on the night of the referendum.

Mayo said on the podcast that the mental health of First Nations people deteriorated during the campaign and that the vitriol caused some supporters to abandon volunteering.

“I think the intensity and the amount of this was unprecedented in this country,” he said.

‘I’m not naive.

“I was on the receiving end. It really becomes quite damaging. It affected the mental health of indigenous people throughout the campaign.’

Mayo described the “painful, painful emptiness in (his) chest” and the “slap in the face” the moment he realized Australia had voted No.

He also criticized the Opposition’s attempts to “deal with race” when, he said, it was “disingenuous” and “misleading people that it was risky”.

“It wasn’t about race,” he said. ‘Indigenous people are not a different race. We are a distinct people with a heritage and culture connected to this place.

‘We deserved the recognition. It was a simple message… but we couldn’t get it across.’

But he did say there was one positive to take away from the referendum result, which was that 40 per cent of Australians – around five million people – voted in favor of the proposal.

Thomas Mayo spoke at the event and criticized the No campaign that opposed Voice.

Mayo says he is heartbroken by the result and acknowledged that there will be no constitutional recognition in his lifetime.

Mr. Albanese and Ms. Burney conceded defeat immediately after the polls closed in Washington, before counting had properly begun. At that moment, there was no longer any path to victory.

While it wasn’t enough to get the Voice over the line, it did “bring this to people’s kitchen tables.” Mayo acknowledged that for many Australians, “the entrenched disadvantage of indigenous people is not something they normally think about.”

Looking ahead, Mayo vowed to continue advocating for the implementation of the Uluru Declaration from the Heart, but not for constitutional recognition.

“I won’t do it as long as I live,” he admitted. ‘But I do think that other people will, because we see in the poll results that young people voted Yes.

“Our children are receiving a different education about the truth of our colonial past and why we have these disparities in the present.”

Despite Mr Mayo’s commitment to the Uluru Heart Statement, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his Labor government have yet to establish their own way forward in the Indigenous Affairs portfolio.

Initially, the plan was to implement a Makarrata Commission to work alongside Voice to Parliament, with the aim of achieving a treaty and truth-seeking process.

But critics say moving forward with that project would directly go against the outcome of the referendum process, even though the referendum question does not explicitly mention Makarrata.

Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney says she is waiting to consult with grieving First Nations communities, who had taken a vow of silence following the referendum defeat, before making concrete decisions.

Yes campaigners had long warned that a No vote would affect Australia’s international standing.

The BBC podcast episode was titled: “What went wrong with Indigenous Australia’s call for a voice?” and introduced Mr. Mayo, along with three academics, each of whom explained why the Voice failed.