It’s a strange feeling to discover at 70 years old that I am Canadian, a full citizen with a passport from a country I barely know. So there is no time to waste in getting to know it.

There’s no point in overlooking the area either. What I need is a top-notch tour of the best spots. I want to see where Buerk’s pioneering ancestors, whom I only recently learned about, helped build the country.

I want to find out where my Canadian father, who abandoned me, had raised another family that didn’t know I existed.

And I’ve always wanted to follow in the footsteps of my hero, George Vancouver, the irascible, vindictive, socially insecure naval captain who discovered nature’s greatest wildernesses.

I miss most of Canada, flying for hours over ice and tundra where there are almost no humans. It is the second largest country on Earth, with almost ten million square kilometres of wilderness, mostly cold.

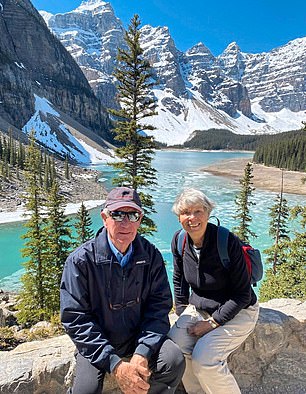

High life: Michael Buerk crosses the Canadian Rockies (pictured) by train, before touring the archipelago of islands stretching north from Vancouver to Alaska

Three-quarters of the population are city dwellers, living within 100 miles of the U.S. border. I fly direct to Calgary. I don’t care about the east. My people were from the Pacific Northwest, the most beautiful and most spectacular part of the country. It doesn’t freeze here for eight months of the year either.

The idea is to cross the magnificent Rocky Mountains on a civilized train and then cruise through the great archipelago of islands, mountains and endless forests that stretches north from Vancouver to Alaska.

The voyage is the brainchild of Regent Seven Seas Cruises, which modestly describes its $500 million Seven Seas Explorer as “the most luxurious ship ever built.” This is no whim, you understand. A newly arrived Canadian wants to see his new country in all its glory.

I always knew that my mother had married a Canadian soldier at the end of the war.

We had lived in Vancouver until her marriage broke down when I was three and she brought me back to Britain. My father never contacted me and my mother died before I was old enough to hear the full story. In any case, the subject was definitely off the table when I was a child.

Michael rides the Rocky Mountaineer, pictured, “the luxury train that offers epic sightseeing for the idle rich.”

Fast forward a lifetime and my son, who had been researching our backgrounds on the Internet, calls me to tell me that he has discovered that the children of Canadians who serve their government abroad are automatically Canadian, even if they have been completely disowned.

The bureaucracy took many months, but eventually my citizenship certificate arrived in the mail, then my dark blue Canadian passport.

Calgary is not the stopping point my grandfather knew.

He was an American civil engineer who came north to run a construction company as the new railway was opening up the Canadian West. Nor is it the ranching town my father passed through, heading off in the opposite direction as an army captain to the war, having changed his name from Carl to Charles to hide our German ancestry.

It is now a large and prosperous city, and at first glance its inhabitants, my fellow citizens, seem to fit the Canadian stereotype: American lite, more sensible, hard-working, scruffier, less likely to shoot you. My taxi driver, a Pakistani immigrant, cannot believe that Canadians obey the rules.

The announcer reveals that he lived in Vancouver (pictured) until he was three years old and returns having obtained citizenship as the son of a Canadian serving the government abroad as a soldier.

The Rocky Mountains are a long white line on the horizon from Calgary. It’s an hour’s bus ride to get to the mountains. They are relatively young. “Only” 200 million years have passed since continental plates folded and fractured beneath the Pacific floor and glaciers began carving out valleys. The peaks, 3,000 metres or more high, are still saw-like and jagged.

Lake Louise is the postcard of the world. The water is turquoise and milky from glacial sediment, and the setting, in a ring of incredibly majestic mountains, is absolutely glorious. You share it with 15,000 other people on a normal day, but that doesn’t matter. It also has an ugly hotel, the Chateau Lake Louise, but that doesn’t matter either – thank God my grandfather helped build it.

My wife Christine and I spent two nights in Banff, a charming little town that somehow manages to welcome four million visitors a year, riding a gondola to the top of the roof of the world, Sulphur Mountain, and bathing in the hot springs that made it famous.

North of Banff is Jasper National Park, where thousands of people were sadly evacuated from their homes last week following a series of wildfires.

LEFT: Michael in his early days in Canada before moving to the UK. RIGHT: Michael and his wife Christine during their trip.

We boarded the Rocky Mountaineer in Banff, the luxury train that offers epic sightseeing for the idle rich (a category I’ve always wanted to belong to). GoldLeaf service means you get an easy chair in the observation lounge of a double-decker car. You head downstairs for a “gourmet” breakfast and lunch, but mostly you sit under the glass dome, sipping cocktails—the first lethal Canadian version of a Bloody Mary is served at 9:30 a.m.

The views are heart-stopping. Literally, it seems. Someone has a medical emergency on the train, though it’s hard to tell if it was due to an overdose of shock or alcohol. It’s late on the second day when we arrive in Vancouver, where I lived as a child. I have no memories of it, good or bad. The first thing I remember is the boat heading home and the family in Solihull falling over at the sound of my Canadian accent.

Vancouver is regularly voted the best city in the world to live in. You can ski at Grouse Mountain in the morning and swim at Crescent Beach after lunch. This is reflected in the property prices – they are more expensive even than London, I am told again and again.

The wooden pier where I played with my tricycle in the 1940s is now the Pacific Place cruise terminal, where we board the Seven Seas Explorer. We cruise a lot (I give talks). There’s something special when a steward shows you to your “stateroom” and asks, “What kind of champagne do you want in the fridge?”

Michael says the massive Hubbard Glacier, seen here, is “one of the most impressive sights in nature” he witnessed on the Seven Seas Explorer cruise ship.

Michael watches sea otters “floating on their backs in rafts” on Hubbard Glacier

Our route follows the pioneering voyages of my flawed hero, Captain Vancouver, a tortured man, but one of the greatest navigators of all time. In the late 18th century, though ill and despised by the young aristocratic midshipmen entrusted to him by the Admiralty, he charted the wild North West, naming much of it after his mentors, his companions or his moods (‘Desolation Sound’, ‘Disenchantment Bay’). He lived on biscuits and rum, and died at the age of 40.

We had caviar for breakfast, lobster for lunch, and Alberta-sized beef short ribs for dinner. For its 700 or so passengers, the Explorer has eight dining options, five of them specialty restaurants of the highest order. Scurvy is not a problem. Captain Van’s HMS Discovery would fit right into the Explorer’s state-of-the-art theater. Its crew was packed, raider-like, into smelly holds and rarely washed.

The views have not changed in centuries: endless, dense, dark pine forest, backed by chain after chain of snow-capped peaks, as Canada merges imperceptibly with American Alaska. The settlements still seem temporary, now living off tourism, after gold, logging and fishing successively experienced their rise and fall.

In Ketchikan, salmon fight shoulder to shoulder to enter the creek, but the biggest attractions are the gold rush brothels, where Popcorn Lil and “Dirty Neck” Maxine plied their trade. Juneau, the state capital, is perched on the edge of an ice field and has a population half the size of Banbury — until the cruise ships come along. Skagway, the gateway to the Klondike, reeks of greed; you can still sense the hysteria for gold. And beyond them all, one of nature’s most impressive spectacles: the massive Hubbard Glacier.

It is a wild place, and still rich with life. Black bears are everywhere; grizzly bears come down to the streams when the salmon run and claw at them. Sea otters, once nearly driven to extinction for their fur, float on their backs in rafts.

And we, the pampered tourists, share the tide-tossed channels with humpback whales that can eat tons of seafood (a million calories a day). That puts even our American shipmates, who dine in their baseball caps and devour immense quantities of Michelin-rated food, in the shade.

Northwest Canada and Alaska are spectacular and take your breath away on cruise ships, much larger than the Explorer. If you choose the right ship and the right weather, you can see some of the most wonderful views on Earth in great detail.

And somewhere out there is the ghost of my father, who roamed this entire coast fishing for rainbow trout, sockeye and pink salmon. And, perhaps, the glimmer of another life he might have had if things had been different. Well, they weren’t. But after some 70 years or more, I can finally say: I’m proud to be Canadian.