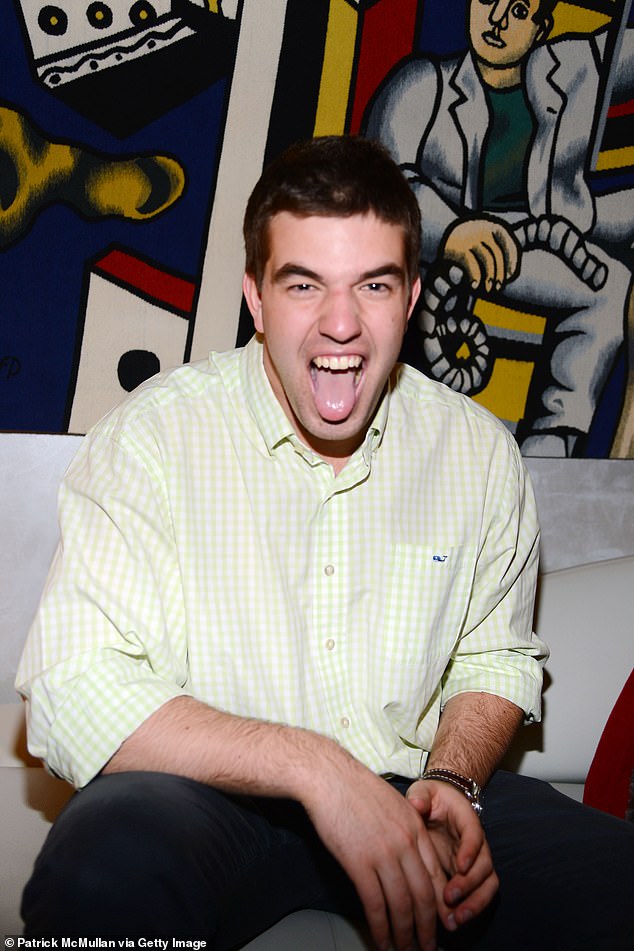

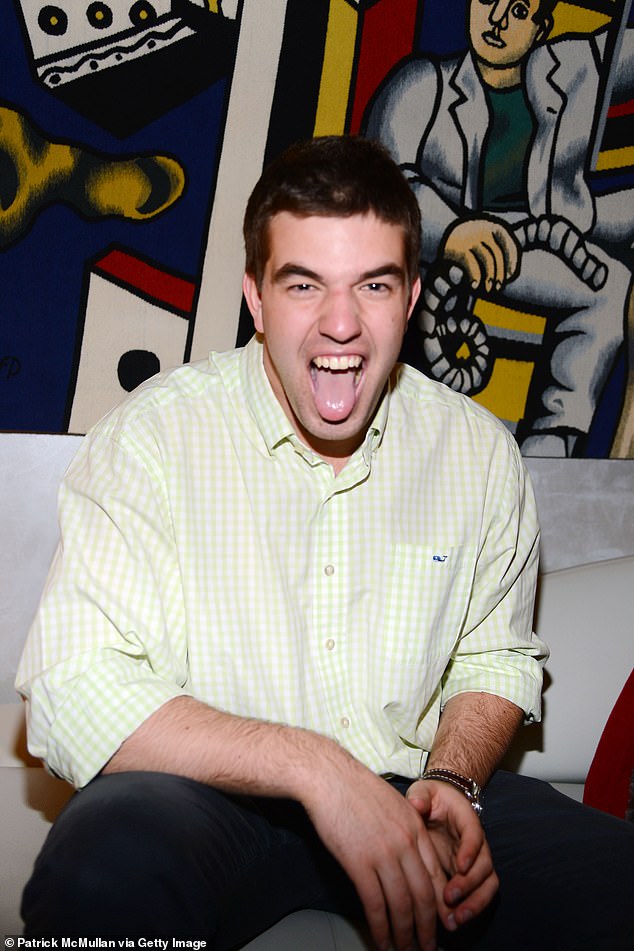

Festival goers and investors who were fooled by Fyre Fest’s Billy McFarland would love to see him get punched in the face, and now they’ll get the chance.

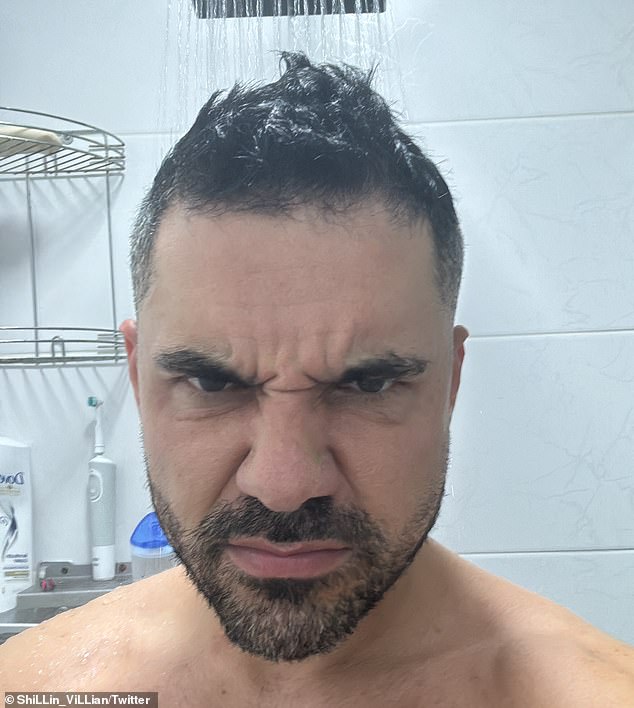

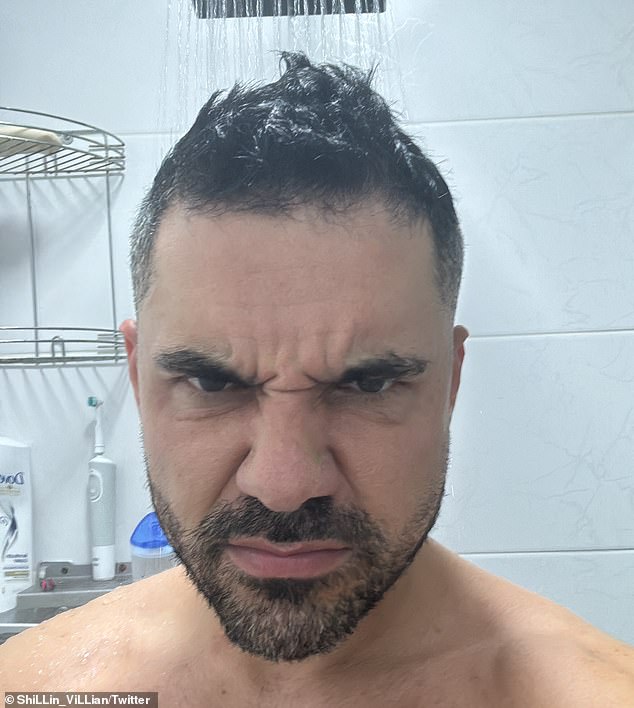

The founder of the infamous festival has agreed to a Karate Combat match against Alex Shillin Villain, a prominent wrestler and crypto influencer, next month in Austin, Texas.

Speaking to DailyMail.com, McFarland, 32, said: ‘I am donating a significant amount of my fight purse towards restitution and people owed in the Bahamas.

“Fyre Festival 2.0 will add more zeroes to the recovery than my surprising debut, but entering the pot is a great way to literally fight to give people their money back.”

McFarland must pay $26 million in restitution after spending four years in prison for his role in defrauding investors in the failed music festival.

Billy McFarland has agreed to a karate sparring match against crypto influencer and fighter Alex Shillin Villain in Austin, Texas, next month.

“I am donating a significant amount of my fight purse towards restitution and owed people in the Bahamas,” McFarland told DailyMail.com. He has been seen training for the match.

He will fight Alex Shillin Villain, a prominent wrestler and crypto influencer, next month in Austin, Texas.

Next month’s fight will be governed by Karate Combat and will take place at a crypto conference called Consensus.

McFarland, a longtime MMA fan, will wear gloves and no helmet, and punches, kicks and knockouts will be allowed.

“This is an incredible life challenge and shows what Fyre is all about,” the scammer said.

When pressed about his opponent, Alex Shillin Villain, McFarland said, “The first Fyre never happened, but knocking out Alex certainly will happen.”

McFarland was at the center of two different documentaries produced by Netflix and Hulu in 2019.

Karate Combat is the world’s leading strike league and the first professional sports league governed and gamified by a bitcoin token, $KARATE.

This comes as McFarland recently revealed that he owes the IRS $7 million in back taxes, on top of the additional $26 million.

The founder of the festival said The US Sun who is still waiting for a second edition of the festival, despite the mountain of debt he is dealing with.

He said, ‘There’s restitution, there’s taxes, there’s everything related to the days leading up to the fire that we’re working on.’

‘The restitution is around 26 million dollars. And I pay that every month, so whatever I make, I literally give a physical check or online payment.

“Plus, there are other people involved in Fyre that I also pay monthly.”

Despite the high numbers, McFarland said, “Right now, it’s all just numbers.”

According to the 32-year-old, he is also leading a more frugal lifestyle these days and is hoping that Fyre Festival 2 will help him with his financial problems.

McFarland said: “(Fyre Festival 2) is the most tangible way to pay back the $26 million I owe, and having real partners gives me the opportunity, over the next five to seven years, to pay back that $26 million.”

Last year he stated that the first batch of tickets for the festival had already sold out and that the event was scheduled for December this year.

The event faced heavy criticism, and people arriving on the island of Great Exuma found incomplete accommodation.

McFarland premiered in March 2022 and took just over a year to announce Fyre Festival II

McFarland was convicted of fraud in 2018 after selling 8,000 tickets, priced between $1,000 and $12,000, for the failed original Fyre Festival.

It was canceled on its opening day, leaving people trapped on the island without many basic services.

A year later, McFarland pleaded guilty to two counts of wire fraud and was sentenced to six years in prison, in addition to paying off investors.

He was also barred from serving as an officer or director of a public company after deceiving investors by altering a stock ownership statement to inflate the number of shares he purportedly owned in a publicly traded company to make it appear that he could personally guarantee the investment. .

McFarland premiered in March 2022 and took just over a year to announce Fyre Festival II.

Ticket holders, who thought they were headed to a “luxury music festival” held on Pablo Escobar’s former private island, were actually lured to a catastrophic event filled with problems with everything from food to accommodation.

Guests, who paid up to $13,000 for luxury packages, were left stranded, with an unfinished shelter, no transportation and no food other than cheese sandwiches served in Styrofoam boxes, images of which quickly went viral.

Guests, who paid up to $13,000 for luxury packages, were left without food other than cheese sandwiches served in Styrofoam boxes, images of which quickly went viral.

At the initial Fyre Festival, McFarland teamed up with rapper Ja Rule to attract millions in investment, promising to host a luxury event, the first of its kind in the Bahamas, with models, DJs, VIP living quarters and extravagant meals.

McFarland paid people like Kendall Jenner to promote the event on Instagram, who released promotional content to entice people to buy tickets for thousands of dollars each.

But the event faced heavy criticism, and people who arrived on the island of Great Exuma found much less than they had anticipated.

Court documents described the scene as “total disorganization and chaos.” The ‘luxury accommodations’ were FEMA disaster relief tents, the ‘gourmet food’ was barely acceptable cheese sandwiches served in Styrofoam containers, and the ‘hottest musical performances’ were nowhere to be seen.