Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” is one of the most famous paintings in the world, recently voted by the British as the greatest work of art of all time.

Painted in 1890, the painting’s legendary swirling background has long been interpreted as a reflection of the artist’s state of mind.

But a new study suggests that the post-Impressionist masterpiece, housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, actually has more scientific merit than history has given it credit for.

Researchers in China and France say it’s an accurate reflection of a windy night, showing “hidden turbulence” – swirling air masses that can’t be seen with the naked eye.

Today, ‘The Starry Night’ is considered his masterpiece, but Van Gogh referred to the painting as a ‘failure’ months after creating it.

The image shows Vincent van Gogh’s famous oil on canvas painting ‘The Starry Night’, which the Dutch painter created in June 1889.

The study’s lead author, Yongxiang Huang, a PhD candidate at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said art “reveals a deep and intuitive understanding of natural phenomena.”

“Van Gogh’s accurate depiction of turbulence could come from studying the movement of clouds and the atmosphere or from an innate sense of how to capture the dynamism of the sky,” the scholar said.

The Starry Night is a famous oil on canvas painting created by Vincent van Gogh in June 1989, a year before his death at the age of 37.

At the time, the Dutchman was in a nursing home in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in southern France, having checked himself in voluntarily following ear mutilation the previous winter.

The iconic painting is a depiction of her view from the window, with bright stars and a crescent moon in the night sky, with the addition of an imaginary village to complement the scene.

The sky is an explosion of colors and shapes, each star encapsulated in waves of yellow and white.

Meanwhile, wind gusts, invisible to the naked eye, are visualized as elaborate swirls, which researchers call “hidden turbulence.”

When he painted The Starry Night, the Dutchman was living in an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in the south of France. Pictured: Self-portrait, c.1887, Art Institute of Chicago

In May 1889, Van Gogh voluntarily entered the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum, housed in a former monastery (pictured) in southern France.

The painting was acquired from a private Dutch collection around 1941 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it is still on display (pictured).

Van Gogh’s brushstrokes create an illusion of sky movement so convincing that it led atmospheric scientists to question how closely it aligns with the physics of real skies.

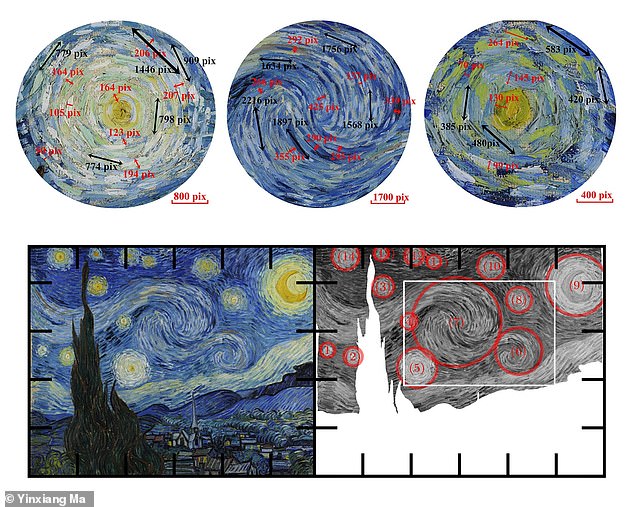

For their study, experts analyzed a high-resolution digital image of the painting to unravel the “hidden turbulence” in the painter’s depiction of the sky.

Specifically, they looked at the painting’s 14 main, rotating shapes and the spacing between the rotating brush strokes that convey a sense of air moving from one point to another.

According to researchers, the painting supports a physics theory called “energy cascade theory.”

This is where air moves from a larger circular stream of air (a ‘vortex’) to a smaller circular stream of air.

It also supports Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov’s theory of turbulence, which describes how energy moves and behaves in a fluid when it flows chaotically or turbulently.

The results suggest that Vincent van Gogh had an “innate understanding of atmospheric dynamics” as he captured them with “astonishing precision”.

The authors measured the spacing of the spiraling brush strokes in ‘The Starry Night’ along with differences in the painting’s luminance, to see if the laws that apply in the physics of real skies apply in the artist’s depiction. The results suggest that Van Gogh had an innate understanding of atmospheric dynamics.

In his new article, published in Fluid physicsThe authors conclude that the Dutchman made a “very careful observation” of turbulent winds.

“He was able to reproduce not only the size of the swirls, but also their relative distance and intensity in his painting,” they write.

It is unclear whether the authors are suggesting that van Gogh had a knowledge of atmospheric physics that we were all unaware of until now, or whether it is simply good luck that the painting lines up with “real-world physics.”

Ultimately, interpretations of the famous work (a scene Van Gogh recreated from memory because he was not allowed to paint in his bedroom) will continue.

At the very center of the painting is its largest swirl, which has been interpreted not as hidden air turbulence but as another galaxy.

American artist and photographer Michael Benson claimed in 2015 that ‘The Starry Night’ is a drawing of the Whirlpool Galaxy, officially called M51a.

The Whirlpool Galaxy is about 23 million light-years away and is roughly the size of the Milky Way, about 60,000 light-years across.

But we know that “The Starry Night” is not an entirely accurate depiction of the scene, as the village of houses and a church with a distinctive steeple was a product of creative license.

Records also suggest that the moon was going through its waning gibbous phase at the time the artwork was made, meaning it would have appeared larger than the crescent depicted in the upper right corner.